Today is September 13, 2012 – the 69th anniversary of the 504 PIR jump into Salerno, Italy. In this post and the next, we’ll continue in our analysis of Bill’s June 13, 1945 letter and in the process discover his role during the 82nd Airborne’s jump into Salerno. While most of the specific details have been lost, some surprising deductions can be made about his participation in that historic event.

“So a few days later we went to Salerno which was a “hot spot”. On the way down to the ground it looked like the whole earth was on fire it was really an ammunition dump on fire. Most of us landed in a spot between our lines and German lines...” Source: William Clark, letter dated June 13, 1945

The Invasion in the Bay of Salerno and the lead up to the 82nd Airborne’s Salerno Jump

The American and British forces of Operation AVALANCHE - units of the US VI Corps and the British 10 Corps – landed on the beaches of Salerno Bay, Italy at 3:30 AM on September 9. The American forces under the command of General Mark Clark, consisted primarily of the 36th and 45th Infantry Divisions with the 36th spearheading the invasion in the southern American sector.

(Note:- the positions and movements of the British, American, and German units can be seen in Map 1 below. Click here for full resolution.)

Map 1: American VI Corps, British 10 Corps and German 1oth Army Movements/Positions 9 – 13 September, 1943

Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993, p. 73 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-6.html

(Click here to view Map 1 in high resolution )

“The British 10 Corps, with the 46th and 56th Divisions, three Ranger battalions, and two Commando units, was to land north of the Sele River, seize the port of Salerno, capture the Montecorvino airfield, take the little rail and road center of Battipaglia, secure the Sele River bridge fourteen miles inland at Ponte Sele, and gain possession of the mountain passes leading to Naples. The 7th Armoured Division was to follow, beginning to go ashore on the fifth and sixth day of the invasion.

The VI Corps, with the 36th Division, was to land south of the Sele River and protect the Fifth Army right flank by seizing the high ground dominating the Salerno plain from the east and the south--an arc of mountains marked by the villages of Altavilla, Albanella, Rocca d'Aspide, Ogliastro, and Agropoli. After the floating reserve--two regiments of the 45th Division--and the rest of the 45th had landed, the 1st Armored and 34th Infantry Divisions, and later the 3d Infantry Division, were to go ashore through the captured port of Naples, which the Allies hoped to have by the thirteenth day of the invasion”. Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993, pp. 43 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-4.html

“Anticipating that 39,000 German troops would be near Salerno on D-day and perhaps a total of 100,000 three days later, the [Allied] planners hoped to send about 125,000 Allied troops ashore. However, the Allied build-up to that figure would be progressive and relatively slow compared with the German capability of reinforcing the defenders.

In the [American] zone, the 36th Division, with infantry components 20 percent overstrength, was to land with two regiments abreast, the third in immediate reserve. Each assault regiment, including attachments, had the enormous strength of about 9,000 men, 1,350 vehicles, and 2,000 tons of supplies. Each was to carry in reserve about seven days of all classes of supply, plus a 20-percent safety factor. All vehicles were to be waterproofed, have their gas tanks and radiators full, and carry five quarts of oil and enough gasoline in cans for fifty miles of travel. All units were to carry basic loads of ammunition plus additional ammunition both combat and cargo loaded, which together would provide an estimated three days of fire. Ammunition to accompany the assault troops totaled 240 rounds per 60-mm. mortar, 300 rounds per 81-mm. mortar, 840 rounds per 105-mm. howitzer, 400 rounds per 155-mm. howitzer, and 300 rounds per 155-mm. gun. For the first three days of the landing operations all convoys were to be combat loaded, thereafter convoy loaded for more economical utilization of ship space” Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993, pp. 49-50 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-4.html

The Americans also had two regiments from the 45th Division floating in reserve bringing the total available manpower in their sector to 36,000. Their opposition was elements of the German 10th Army which occupied the Salerno area and was commanded by Colonel-General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, a savvy hardened veteran commander of the Russian Front. At the time of the invasion, the 10th only had one fighting unit active in the Salerno Bay area – the 16th Panzer Division.

Colonel-General Heinrich von Vietinghoff. Commander of the German 10th Army in Italy in 1943

Source: Wikipedia commons

“Meeting the Americans, and the British as well, on the beaches of Salerno were troops of the reconstituted 16th Panzer Division, the only fully equipped armored division in southern Italy. Not quite at full strength, the division had 17,000 men, more than 100 tanks, and 36 assault guns organized into four infantry battalions, one equipped with half-tracks for better support of tank attacks, and three artillery battalions. Morale was good. Shortcomings were lack of combat experience, a shortage of gasoline, which restricted training of tank crews, and a long front of more than twenty miles.” Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993, p. 78 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-6.html

Even with the powerful 16th Panzer Division, and the advantage of occupying a highly defendable territory typified by rugged mountains and deep ravines, on the morning of September 9 the German’s were vastly outnumbered in comparison to the immense Allied invasion fleet. There were a variety of reasons for their predicament.

Two key divisions were denied movement south to Salerno because the German High Command expected other Allied invasions to come further up the coast above Salerno. Units escaping from the south in response to the British Operation Slapstick were expected to arrive in the Salerno area earlier than they did. When they did arrive confusion reined about whether they should stay or move on to Rome as was originally planned. In any case the units which were ordered to move to the Salerno area were understrength or in the process of reorganization from being pounded by losses sustained during the Sicily campaign. The Hermann Goring Division and the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division both being cases in point. On top of all this, fuel shortages hampered movement; and communications between General Vietinghoff, General Kesselring (the supreme German commander of Italy based in Rome), and Headquarters in Berlin were intermittent.

The poor communications in particular had a significant impact on General Vietinghoff’s decision making. Upon seeing the size of the Allied armada in the Bay of Salerno early on September 9, he was convinced it was the main Allied invasion. It was so large he surmised that the risk of other Allied invasions up the western Italian coast was low. Unable to contact General Kesselring for any advice on the matter he alone shouldered the decision to pull out and head for Rome, or stay to counterattack. His decision was to stay with the objective of defeating the Allies in what he correctly concluded was their main northern invasion force – the other being the British 8th Army moving up from the southern tip of the Italian peninsula.

The immediate forces at Vietinghoff’s disposal, while depleted, were still formidable. Together the Hermann Goering, 16th Panzer, and the 15th Panzer Grenadier Divisions totaled 45,000 men with some strong artillery forces and significant armored vehicles and Tiger tanks. Vietinghoff knew this might not be enough, so he was counting on the timely arrival of the German 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, scheduled to reach the Salerno vicinity on the evening of September 9. Lead elements of the 26th Panzer Division were anticipated to arrive the next day. Both divisions were evacuating from southern Italy, but unforeseen landings by another set of British forces in the south delayed their departure. They didn’t make it until September 10 and 11, respectively and then only in dribs and drabs of small unorganized groups. It wasn’t until the evening of September 13 that these units were sufficiently organized and of the large enough numbers that Vietinghoff began discussing using them to mount an effective counterattack against the beachheads being established by the Allies.

The combined manpower of the 26th and 29th Divisions was 30,000 – not to mention their tanks, armored vehicles and substantial artillery. The total expected base of manpower when added to the men already deployed in the area would have totaled 75,000. Had the southern German forces arrived in Salerno on time, the eventual outcome of the invasion could have been very different. Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993, p. 67 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-5.html

Vietinghoff’s decision to attack was made more risky when the bombing and artillery might of the combined Allied air and naval forces were considered. Both of which were far superior to that of the Germans. Fully aware of this, Vietinghoff believed that if he could gather all his available forces early enough he could overwhelm the Allies in a Blitzkrieg style attack, quickly destroying them before the navy and army air forces could respond.

After news of the invasion armada eventually reached General Kesselring in Rome, he and Vietinghoff asked for two Panzer Divisions to be sent south from their stations in Mantua, northern Italy to help repel the invasion. German High Command in Berlin denied the request. Had they actually been sent, it is almost a foregone conclusion that the outcome of the Salerno campaign would have meant annihilation for the Allies.

While waiting for the southern reinforcements, the 16th Panzer Division had earlier mined the invasion area and placed obstacles such as barbed wire. They also used psychological warfare methods (AKA PSYOPs) in the form of load speakers in the Paestum beach landing area declaring “Come on in and give up. We have you covered.” The men of the 36th Division ignored them, but there were other instances of PSYOPs used. For instance, the Germans played “Deep in the heart of Texas” when the Texas based 36th Division fought further inland.

Troops of the 36th Division landing on the invasion beaches

Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993 p. 89 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-6.html

At 7:00 AM on September 9, the 16th Panzer Division attacked the Allied landing beaches in both the British and American zones with tanks and infantry, but were beaten back by the then untested, yet effective US 36th Infantry Division and the seasoned British 46th and 56th Divisions fighting to their left. Click on Map 1 above to see these details in high resolution.

If the Germans were experiencing problems organizing their retreating and depleted divisions into a worthy adversarial force, the Allies were having their own. Right from the beginning there was seven mile gap between the American positions to the south and the British forces invading on their left flank in the north. The gap opened because while moving toward their respective objectives, the British forces had gone to the northeast to engage the Germans in their sector while the US 36th Division had advanced east to do the same in theirs. Due to the slow build up on shore of the Allied forces there was insufficient men and machines to maintain a continuous front across both Allied sectors.

Over September 10 and 11 General Vietinghoff scrambled to assemble a force strong enough to slam the Allied invasion and annihilate it’s forces on the beaches before the survivors could escape by sea. Eventually he was able to cobble together an attack group consisting of units from the 26th Panzer Division and the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division retreating from the south. He used them to reinforce the 16th Panzer Division around the towns of Battipaglia and Eboli.

To the north in the British sector he used the Hermann Goring Division and the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division to attack the British who in the face of the onslaught were entirely committed to holding onto their own gains.

Meanwhile on September 10 the Allied forces were making good progress inland. The beachhead around the landing zones continued to be established inland positions expanded. Some nine miles west of Salerno, H Company of the 504th PIR and US Ranger units made a landing on the beaches around Maiori on the north side of the bay. Company H and seized the high ground around the Chiunzi Pass.

Plans were ready to be implemented for further gains in Salerno Bay area:

“The VI Corps plan for 11 September envisaged three separate but related attacks. On the left, the [45th Division’s] 157th Infantry was to cross the Sele River downstream from its junction with the Calore and attack north to Eboli. Seizure of Eboli, about eight miles from the Sele, would strike the German flank and rear and perhaps pry loose the German hold on Battipaglia; it would also facilitate 10 Corps' capture of the heights immediately overlooking the Montecorvino airfield. In the center, the [45th Division’s] 179th Infantry was to enter the Sele-Calore corridor near the juncture of the two rivers. Covering the right flank of the 157th, the 179th was to drive seven miles northeast across the flood plain to seize a bridge, Ponte Sele, and cut Highway 19, a good lateral route still open to the Germans. On the right of the low ground, a regiment of the 36th Division was to secure Hill 424 near Altavilla and deprive the Germans of a commanding view over much of the beachhead, as well as the flood plain, the valleys of the upper Sele and Calore Rivers, and portions of Highways 19 and 91”. Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993 p. 104 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-7.html

On September 11, the 142nd Regimental Combat Team of 36th Division which was spearheading the US part of the invasion had penetrated as far inland as Altavilla, passing the town, to take Hill 424, the strategic high ground in the area. They seized the town of Albanella in the south. At that time and to the left of the 36th Division’s 142nd Infantry, the 45th Division’s 179th Infantry, facing heavy German resistance, had pushed from the town of Persano and were making their way toward the Ponte Sele – the bridge over the Sele river. The 179th’s rear was exposed in the event of a German counterattack, so the 157th Infantry of the 45th Division was brought forward from reserve to secure the crossings west of the Sele river around Persano to prevent any German attack.

Despite these reinforcements made by the 45th Division a gap between the British and the Americans fluctuated in size, but persisted throughout the operation. The area of the gap and the troop deployments as of September 11 are shown in Map 2 below.

Map 2: Troop positions & gap between British and American forces on 11 September, 1943

Adapted from Source: “SALERNO: American Operations From the Beaches to the Volturno 9 September - 6 October 1943”. P. 48 1990. Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/salerno/map07.jpg

A key strategic point in the area was a combination of a patch of higher ground offering the best visibility of the surrounding terrain and the network of roads leading up through the Sele Calore river area. The patch of higher ground was centered around collection of five buildings constituting a tobacco factory and a nearby farmhouse to the north. The force occupying the factory area would more easily hold the Sele and Calore river crossings, and would control access to the roads used for German advance, supply and if necessary, escape. Intimately aware of all the strategic locations in the area, the Germans naturally occupied the tobacco factory and surrounds from the moment the invasion began.

The tobacco factory; a key strategic location on high ground near vital road junctions and river crossings

Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993 p. 104 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-7.html

What the Germans may or may not have known at this time was that this strategic point also happened to be in the location of the gap between the US and British lines. On September 11, the American 157th Infantry tried but - in the face of intense German resistance - failed to take the factory. Control of the factory was vital since it would mean the 142nd Infantry’s rear would be protected in the event of an anticipated German counterattack. The tobacco factory changed hands several times in the afternoon of September 12 with the American 157th Infantry finally holding it at the end of the day.

What the Germans did know is the strategic importance of retaking Hill 424 (now in possession of the 36th Division) with its commanding views of almost the entire invasion area. Hill 424 was the most valuable piece of real estate in the American part of the invasion zone. Once it was in German hands, the positions and movements of all the American units could easily be observed.

Elements of the 29th Panzer Division began to arrive from the south on September 10 and the 26th Panzer on September 11. While he waited for more units from these divisions, Vietinghoff decided to the throw the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division against the US 36th Division occupying Hill 424. See Map 3 Below.

“During the night of 11/12 September enemy units of the 2d Battalion, 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, began to infiltrate around Hill 424. At daybreak on the 12th our troops received fire from so many directions that the enemy seemed to be everywhere. Our artillery, lacking definite targets on Hill 424, fired concentrations on enemy troops and tanks between the Sele and Calore rivers. Enemy artillery was also active, and fired for 2½ hours on Hill 424, beginning at 1100 [11:00 AM]. Communications were severed; no amount of work could keep the lines open.” Source: “SALERNO: American Operations From the Beaches to the Volturno 9 September - 6 October 1943”. p. 54 1990. Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/salerno/sal-germancntr.htm

The 15th Panzer Grenadier attack on 1st battalion 142nd Infantry (36th Division) occupying Hill 424 and in the village of Altavilla killed or captured over 500 men. There were 260 survivors who became encircled before making their way out under cover of darkness to friendly lines.

At around 6:00 AM, on September 13 (AKA Black Monday to Salerno veterans) three Battalions from the 36th Division attempted to retake Altavilla and Hill 424. The 3rd Battalion, 143rd reached the town and its Company K held it. The remainder of the battalion decided to try and advance on Hill 424, but was driven off by swift and savage assaults of extremely accurate artillery barrages and small arms fire from the 15th Panzer Grenadier’s. The battalion retreated. Company K became trapped in Altavilla and couldn’t escape for another day. The other battalion (3rd Battalion, 142nd) fought up the slopes to the summit of Hill 424. The 260 remaining men from 1st Battalion 142nd Infantry were sent to reinforce the attack. They didn’t make it because they were shelled so badly by artillery that a mere 60 men were left to fight. 3rd Battalion 142nd were penned down by artillery, then without the reinforcements from 1st Battalion, were thrown back by fierce German counterattacks and forced to retreat. Source: “SALERNO: American Operations From the Beaches to the Volturno 9 September - 6 October 1943”. p. 60 1990. Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/salerno/sal-germancntr.htm

The German response was a new and unexpected experience for the 36th Division. It marked a change in their tactics from mainly defensive probes to decisive attacks designed to rapidly overwhelm and defeat their opponents.

Map 3: German Attacks and American Retreats at Altavilla 13 September, 1943

Source: “SALERNO: American Operations From the Beaches to the Volturno 9 September - 6 October 1943”. P. 59 1990. Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/salerno/map07.jpg

Around the Eboli area by the morning of September 13 enough units of the 26th and 29th Panzer Divisions had arrived to convince Vietinghoff that by September 14 sufficient German armor and men would be available for a massive counterattack striking down from Altavilla through the Sele-Calore river corridor, then pursuing the Americans across the Salerno plain towards the invasion beaches at Paestum where any remaining pockets of resistance would be destroyed.

At about the same time, from the newly acquired observation posts on the hills behind Altavilla, the Germans – for the first time – saw the gap between the British and American positions.

“With some astonishment he [Vietinghoff] inferred that the Allies had voluntarily ‘split themselves into two sections’. To Vietinghoff this meant that the Allies were planning to evacuate their beachhead, and he seized eagerly upon that conclusion. The arrival of additional ships off the Salerno beaches he construed as those necessary for the evacuation. The Allied use of smoke near Battipaglia he regarded as a measure designed to cover a retreat. The translation of an intercepted radio message, which seemed to indicate an Allied intention to withdraw, made him certain that the Allies had been unable to withstand the heavy and constant German pressure and were in fact about to abandon their beachhead. He interpreted German propaganda broadcasts claiming another Dunkerque as support for his conviction.

Sensing victory, Vietinghoff wanted all the more to launch a massive attack, no longer to drive the Allies from the beaches but now to prevent their escape. More and more pressure, he urged his subordinates.

Shortly after midday on 13 September……elements of the 29th Panzer Grenadier and 16th Panzer Divisions struck from Battipaglia, Eboli, and Altavilla. Not long afterward the corps commander, Herr, reported his troops in pursuit of the enemy.” Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993. pp. 112– 113 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-7.html

What came next was nothing short of a berserker like attack aiming at total annihilation of the Americans. Based on their earlier assessment the German’s believed they were in pursuit of an evacuating American force. Vietinghoff seized on this belief and ordered all available forces to attack south of Eboli vowing that no Americans would leave Salerno. At 3:30 PM September 13, a column of over 20 panzers supporting 1st Battalion 79th Panzer Grenadier Regiment of the 16th Panzer Grenadier Division attacked down the Eboli road. They and broke through the 45th Division’s 157th Infantry lines overruning the tobacco factory and killing or capturing 0ver 500 men. The Germans blasted through the American positions reaching a bridge over the Sele River near Persano.

Map 4: German Attacks and American Retreats 13 September, 1943

Source: “SALERNO: American Operations From the Beaches to the Volturno 9 September - 6 October 1943”. P. 64 1990. Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/salerno/map07.jpg

The 36th Division’s 2nd Battalion, 143rd Infantry was next in the the path of this juggernaut as it veered left and headed east toward them. The 2nd Battalion was sandwiched between them and a 29th Panzer Division force attacking from the opposite direction. Their positions were quickly overun and 500 of its men were lost, most taken prisoner. About 400 men did manage to retreat to relative safety.

The lightning German attack continued unabated.

“By 1715 [5:15 PM] a sizable force of German tanks and infantry was in the corridor unopposed, and by 1800 [6:00 PM] enemy artillery was emplaced around Persano. Soon afterward, fifteen German tanks headed straight toward the juncture of the Sele and Calore Rivers. Their advance was accompanied by a display of fireworks--an extensive use of Very pistols, pyrotechnics, and smoke--intended either to create the appearance of larger numbers or to denote the attainment of local objectives. By 1830 [6:30 PM] German tanks and infantry were at the north bank of the Calore.

Between them and the sea stood only a few Americans, mainly the 189th and 158th Field Artillery Battalions. In positions on a gentle slope overlooking the base of the corridor, the batteries of these battalions opened fire at point-blank range across the Calore and into heavy growth along the north bank of the river. At General Walker's command, a few tank destroyers of the 636th Battalion coming ashore that afternoon hastened to the juncture of the rivers to augment the artillery. Howitzers of other battalions and tanks in the area added their fires where possible.

Immediately behind the artillery pieces, only a few hundred yards away, was the Fifth Army command post. While miscellaneous headquarters troops--cooks, clerks, and drivers--hastily built up a firing line on the south bank of the Calore, others hurriedly moved parts of the command post to the rear. The spear that General Clark had visualized poised at the center of the beachhead had struck.” Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993. pp. 115 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-7.html

In the face of the inexorable assault, and as imagined by Vietinghoff , General Clark seriously did consider an evacuation. Hasty plans had drawn up for a variety of evacuation procedures. One called for an evacuation of American headquarters to an offshore location:

“Finding the situation ‘extremely critical,’ facing squarely the possibility ‘that the American forces may sustain a severe defeat in this area,’ General Clark arranged to evacuate his headquarters on ten minutes' notice and take a PT boat to the 10 Corps zone, where the conditions were better for maintaining what he called a ‘clawhold’ on Italian soil”. Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993. pp. 115 - 116 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-7.html

Indeed while some of the German commanders didn’t think the Allies were evacuating, Kesselring and Vietinghoff were both convinced of it.

“To Vietinghoff, German success seemed to be within grasp. He was so sure of victory by 1730 [5:30 PM] that he sent a triumphant telegram to Kesselring. ‘After a defensive battle lasting four days,’ he announced, ‘enemy resistance is collapsing. Tenth Army pursuing on wide front. Heavy fighting still in progress near Salerno and Altavilla. Maneuver in process to cut off the retreating enemy from Paestum.’” Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993. pp. 116 - 117 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-7.html

By the evening of September 13, a German 10th Army diary entry read “ The battle of Salerno, appears to be over”. Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Salerno to Cassino”, Blumenson, M., 1993. p. 117 http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-7.html

They had retaken not only Persano, but Altavilla, Hill 424, Albanella and all of the roads connecting those towns. From this commanding position it would be easy for Vietinghoff to achieve his objective.

However, the German units were within naval artillery range, so US and British ships attacked with devastating barrages from their huge guns. The situation was still precarious, however since the German forces had penetrated very close to the beaches.

“So a few days later we went to Salerno which was a ‘hot spot’”. – William A. Clark , 1945

General Clark felt that the whole operation was in danger of becoming another Dunkirk. He turned to his Airborne adviser, Bill Yarborough who put together an Airborne plan to drop around 1,200 paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne into the area. The plan would boost morale of the shattered 36th and 45th Infantry as well as plug the hole in the gap between the 45th and British forces.

At about 12:00 noon on September 13, General Clark wrote a letter to General Ridgway requesting the urgent drop of paratroopers into Salerno. A fighter pilot volunteered to deliver the message and took off for Licata airfield where General Ridgway was stationed. Ridgway received the letter after some drama and expense of valuable time since the pilot was ordered by Clark to give the letter to Ridgway and no one else.

This was an emergency situation. In a scaled back version of GIANT I, The 505th was at the time preparing for their drop on Capua to secure the bridgeheads on the Volturno River, so using them was out of the question. Instead Ridgway chose Colonel Reuben Tucker’s 504th PIR for the jump.

Fears of another Sicily like friendly fire attack were very real. While the route for GIANT II had been set up to eliminate the possibility of Allied friendly fire, there was no time to plan and implement similar measures for this impromptu mission. To reduce the chances of a repeat of the July 11 tragedy, Ridgway ignored the chain of command – General Alexander, in particular – by radioing Clark’s headquarters directly. His message asked Clark to order all Allied forces to withhold firing on any aircraft from 9:00 PM onwards unless ordered otherwise. Clark complied, giving instructions to his staff accordingly to inform all such forces not to fire on aircraft. Source: “Ridgway’s Paratroopers” Blair, C. Carter, R., 1956, p.150

Troop Carrier Command rushed to inform those antiaircraft batteries stationed in Sicily about the flight. Source: “Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942 – 1945” USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1955 P. 61

The plan was implemented all too quickly. C-47’s from the 61st, 313th and 314th Troop Carrier Groups were moved about to the airfields of Trapani and Cosimo where Tucker’s 1st and 2nd Battalions were to take off. Colonel Gavin of the 505th was sent to meet with with Tucker and his officers at their bivouac and in short order informed them of the plan. source: Source: “All American All the Way” Nordyke, P., 2005, page 106

504 PIR Paratroopers loading for equipment packs delivery via parachute late in the day September 13, 1943

Source: Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942 – 1945 USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1955 P. 63

Just before the 1st battalion 504 was loaded onto the planes to make the Salerno jump Colonel Tucker, in the short time available, made a notable motivational speech to his troops.

“A jeep drove up. Colonel Reuben Tucker, the regimental commander, was standing up in it, his flushed, be mustached intense face set in deep lines. He halted at every plane and yelled ‘Men, it’s open season on Krautheads. You know what to do!” Source: “Those Devils in Baggy Pants” Carter, R., 1951, p.44

Colonel Ruben “Rube” Tucker Commander of the 504th PIR

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Tucker’s attitude was something he very effectively instilled in his troops, from his officers down through all of his personnel. Here’s a quote from one of his platoon leaders before the Salerno jump:

“Men here’s the [****]. Those goddamned Krauts are kicking the hell out of our straight-legs [non paratroopers] over at Salerno. Mark Clark wants us to rescue his boys. When the green light comes on, jump. When you hit the ground, be ready for anything. We’re supposed to drop behind our own lines – but the krauts might be on the DZ when we get there. Any questions?” Source: “Geronimo!: American Paratroopers in WWII” Breuer W., 1989, p. 127

According to Gerard Delvin in his book Paratrooper!:

“Paratroop company commanders were given only sketchy information to pass on to their platoon leaders. By the time the work got passed down to the infantry squad level, the briefings went something like this: ‘The Krauts are kicking the [expletive] out of our boys at Salerno. We’re going to jump into the beachhead tonight and rescue them. Put on your parachutes and get on the plane – we’re taking off in a few minutes for the gates of hell.’” Source: Paratrooper!” Devlin, G., 1979 p. 301

The troop carrier pilots were just as quickly informed of the mission:

“There, while the men of the 504th were climbing aboard the planes, the troop carrier personnel were briefed “by the light of a few flashlights and maps held up against the side of a plane” Source: “Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942 – 1945” USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1955 P. 61

There were serious omissions on the mission’s specifics including a lack of aerial photographs and a reliance on oral instructions which caused much confusion amongst the pilots. It seems miraculous that no serious errors were made.

Troop carrier pilots attending a hasty impromptu flight briefing using flashlights and map on a dark C -47

Source: Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942 – 1945 USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1955 P. 64

Just to make sure that the mission did not succumb to antiaircraft attack, the planes flew up from the south hugging the east coast of Italy after rendezvousing off the northeastern tip of Sicily.

Map 5: Proposed and Actual 82nd Airborne Missions

Note: - Actual Mission hugs the coast of Italy and ends at the drop zones (DZ) around Salerno

Source: Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942 – 1945 USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1955 p. 55

This jump was the first time Airborne Pathfinders were used in combat. They left ahead of the main armada and dropped successfully setting up their equipment which would guide the rest of the planes to the correct drop zone.

“On the way down to the ground it looked like the whole earth was on fire it was really an ammunition dump on fire.” – William A. Clark , 1945

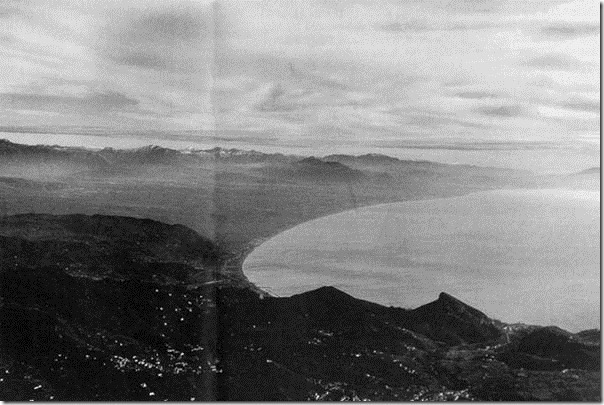

The Bay of Salerno looking down from the north.

Note: The C-47s flew in from the south – the opposite perspective from this photograph

Source: National Archives http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/naples/72-17.htm

The 1st Battalion took off from Cosimo airfield, Sicily on planes from the 61st and 314th Troop Carrier Groups. As part of the 2nd battalion, Bill’s C-47 took off at around 8:40 PM on September 13 from Trapani/Milo Airfield, Sicily where the 313th Troop Carrier Group was based. The 313th carried all of 2nd Battalion 504th PIR into Salerno in 36 planes. Two planes had to turn back due to mechanical trouble. There was one spare plane back at the airfield and into this C-47 one stick of troopers climbed aboard. It quickly caught up with the rest of the 313th. At around 11:26 PM on September 13, Bill jumped at an altitude of 800 feet along with the other 35 planeloads of paratroopers from 2nd Battalion. Source: Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942 – 1945 USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1955 pp. 61-62

Bill wrote that when he jumped he saw an ammunition dump on fire. I can’t find a reference to this in any of the documents on the jump. One can reasonably assume that there were ammunition dumps aflame in places since there were many precarious battles being fought at the time. The German’s were still executing their massive counterstrike. Artillery and air raids were continuous. Fires were burning in many locations.

On the ground a large T Half a mile long and wide marked the drop zone which was made of drums of sand soaked in gasoline and lit when the planes were in range. The jump was a success with most of the troopers landed within 200 yards of the DZ and all of them within 1 mile of it. Source: “Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942 – 1945” USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1955 P. 62

Map 6: 504 PIR Drop Zone (DZ) on the night of 13 (and early morning of 14) September, 1943

Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations Salerno to Cassino.” Blumenson M., 1993, page 128. Retrieved December 14, 2011 from http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-8.html

Due to mechanical problems with some of the 51 planes assigned to fly the 1st Battalion and the Regimental Headquarters Battalion, Colonel Tucker’s serial was late in taking off. The 2nd Battalion serial commanded by Dan Danielson decided not to wait at the rendezvous site for 1st Battalion. Because of radio silence, the decision could not be relayed to Tucker, nor General Clark or anyone else. Source: “Geronimo!: American Paratroopers in WWII” Breuer W., 1989, p. 130

“Tucker paced about like a tiger in a cage, became impatient, and ordered his C-47’s to lift off solo, in pairs and in small groups.” Source: “Geronimo!: American Paratroopers in WWII” Breuer W., 1989, p. 130

The 1st Battalion serial flew in a disorganized fashion, not properly formed in a V of V formation and was dispersed over 300 miles. General Clark’s staff were becoming increasingly worried about the fate of the Colonel and the rest of his men. The first planes from the serial arrived at around 2:30 AM. Subsequently 1st Battalion was late in arriving at the DZ. Source: “Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942 – 1945” USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1955 P. 62

At 4:30 AM on September 13 Colonel Tucker reported to General Dawley “‘How soon can you assemble your regiment?’ the corps commander asked. ‘They are assembled now and ready for action.”’ the colonel replied. Source: “Geronimo!: American Paratroopers in WWII” Breuer W., 1989, p. 131

Seventy-six men were injured and 120 troopers from Company B were missing. The missing troopers were to rejoin the force later. Source: “Geronimo!: American Paratroopers in WWII” Breuer W., 1989, p. 131

“With daylight, a curious phenomenon swept through the ranks of the beleaguered and weary GIs and Tommies on the fireswept and shrinking bridgehead. Scores of them had stood in their fox holes and cheered lustily when they had seen Tucker’s men bailing out. Word that 1,300 tough American paratroopers had leaped onto the battlefield, like lightening from the black sky, infected haggard and demoralized men with a new sense of confidence, even buoyancy. The spiraling boost to sagging Allied spirits was grossly disproportionate to the relatively small number of parachutists involved. This was the ‘psychological reinforcement’ about which Bill Yarborough had spoken to General Clark.” Source: “Geronimo!: American Paratroopers in WWII” Breuer W., 1989, p. 131

“Most of us landed in a spot between our lines and German lines…” – William A. Clark , 1945

In his letter Bill stated that most of the paratroopers landed in a place between the Allied and enemy lines. On September 13th the lines were as pictured in Map 6 above. What he is referring to is the gap between the British and US forces which was being exploited by the advancing Germans.

After Colonel Tucker arrived he and his key staff had a briefing of the situation and were assigned their objective. They were told of the situation at Altavilla and the German’s advance through the gap between the lines where they had overrun the 36th and 45th Divisions positions and movement towards the American landing beaches at Paestum. The 504’s mission was to fill that gap.

Tucker gave orders for 2nd Battalion to deploy in the gap. He assigned 1st Battalion to their right of this area, on the slopes of Mt. Soprano. Source: “All American All the Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2005, p. 107

They were to “hold to the last man and last round”. Source: “More Than Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2008, p. 80

The 1st and 2nd battalions of the 504 were assembled within an hour of landing. They were placed on trucks, driven part way, then marched the rest of the way to their positions about eight miles from the drop zone near Mt. Soprano. On arrival they began digging in and were finished by 3:00 AM on September 14th. Source: “More Than Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2008, p. 80 – 82

“Word was passed to expect an attack later that morning. In the predawn darkness, the two battalions put out listening posts and patrols toward Albanella in order to gain advanced warning of any German assaults.” Source: “More Than Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2008, p. 83

C Company 504th paratrooper, Ross Carter, in his poignant book, “Those Devils in Baggy Pants”, writes:

“It was three o’clock in the morning of September 14, 1943. We didn’t know where we were on the beachhead and few of us ever learned much about it except that we had jumped at a place called Paestum, just south of Salerno. All next day, hidden in a small valley we listened to a terrific battle taking place a couple of miles away. We were in position to repel the attack if it reached us, but it never did. That night we put out guards and finished digging foxholes.” Source: “Those Devils in Baggy Pants” Carter, R., 1951, p. 45

In the morning of September 14 it was discovered that the enemy appeared to be massing for a drive through the line held by Bill’s 2nd Battalion and units of the 45th Division. General Veitinghoff had ordered everything thrown at the Allies to finish them off. He still believed they were evacuating. At 8:00 AM tanks and infantry from the 16th Panzer and the 29th Panzer Grenadier Divisions, attacked from their positions south of the Sele River. They were met by infantry from 45th Division’s 179th Infantry deployed to the left of Bill’s battalion. Unaware of the new US reinforcements effectively plugging the gap, the Germans found themselves in a pitched battle. Artillery strikes from land and sea were called in destroying several of the tanks, causing the infantry to retreat. The artillery deterred the Germans from making a decisive thrust through the US lines. However, during the day the Germans made further exploratory attacks against the 504 2nd Battalion and German artillery fell on their positions. The Germans were probing, trying to find a weakness in the line through which they could make a panzer led Blitzkrieg strike to the landing beaches where reinforcement troops and supplies were still being unloaded. Source: “More Than Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2008, p. 84 Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations Salerno to Cassino.” Blumenson M., 1993, page 129. Retrieved December 14, 2011 from http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-8.html

Throughout the day the Germans launched more attacks. The fine dirt of the Salerno plain thrown up by German armored vehicle movements and the enemy’s use of smoke camouflage easily gave away their positions. Allied superiority in land based artillery and naval gun fire proved to be effective against any German advancement.

On the evening of September 14 the situation seemed to be under control – at least from the viewpoint of securing the beachhead. The line had held despite continued exploratory attacks by the Germans. In an effort to gain vital intelligence on enemy movements and intentions, Tuckers two 504 battalions were sending patrols up to 3 miles in front of their lines.

In the meantime more reinforcements were arriving. The 325th Glider Infantry Division with all but their Company H had landed on the Paestum beaches. The 45th Division’s, 180th Infantry was moved from floating reserve and deployed near Mount Soprano. During the night of 14/15 September the 505 PIR parachuted into the DZ at Paestum with and additional 2,100 paratroopers. Now the Americans had several thousand more men to throw into the fight.

At Kesseling’s headquarters in Rome, on September 14, it was becoming more apparent that the Allies were not evacuating. However, he still wanted Vietinghoff to attack with the aim of destroying the Allied beachhead in order to gain favor with the German High Command in Berlin. Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations Salerno to Cassino.” Blumenson M., 1993, page 131. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-8.html

For the Germans, with the forces they had, the Allied naval and air bombardments proved too powerful to make a strike at the beach successful. On September 15 Kesselring advised Vietinghoff to attack in the hills above the bay out of range of the naval guns. Attacks that day against Allied positions on the Salerno plain were small and insubstantial. Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations Salerno to Cassino.” Blumenson M., 1993, page 133. Retrieved from http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-9.html

The Germans began pulling out towards the Sele-Calore river junction. By the end of September 15, the Allies began to understand the Germans were retreating. Vietinghoff got approval from Kesseling to withdraw from the battle due to the overpowering might of the naval artillery and the threat posed by the British approaching from the south now a mere 50 miles away of Paestum. Source: “United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations Salerno to Cassino.” Blumenson M., 1993, page 134. Retrieved from http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-MTO-Salerno/USA-MTO-Salerno-9.html

On the American side there was less concern that the beachhead was vulnerable. Plans for an evacuation were abandoned. General Clark congratulated the men. The Allies began thinking of the next steps. The first was an attack on Altavilla to retake the strategic high ground of Hill 424.

The mission of taking Hill 424 and its commanding views of the invasion beaches now fell to the 504 PIR. It was to be a costly one.

© Copyright Jeffrey Clark 2012 All Rights Reserved.

![Italy-Proposed-and-Actual-missions_t[1] Italy-Proposed-and-Actual-missions_t[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj7UCG7UuXqbeU8ZYtHyHigsrc5luEQEyW_ez6HOvlOL7nG7NF3h72ZJDAnPIrApePKPLWX7aTCQ173IFi4N0ypGCSHu1spQkEfmOTOD2PYCaFjKIBqhrUu9HUsieR3ILWfV4HWjRPlyjo/?imgmax=800)

Thanks for your blog. It is great reading every time I come back on it.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting stories. My father was a paratrooper during WWII assigned to the 47th troop carrier squadron 313th troop carrier group. He received 7 bronze stars for action in Normandy, Southern France, Northern France, Central Europe, Ardennes, Rome-Arno and Rhineland. He passed during January 1991. He never shared his experiences with anyone and rarely spoke about the war. Thank you sharing your uncle's stories and many other details of various battles.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your efforts. Dad was in F-Company, 141st, 36th and was there all way through France were he was severally wounded. He talked about when the paratroopers came. Thank you again. http://www.texasmilitaryforcesmuseum.org/36division/archives/memorial/cahoon.htm

ReplyDelete