Bill’s First Impressions of Berlin

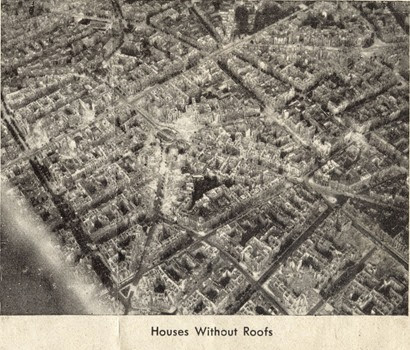

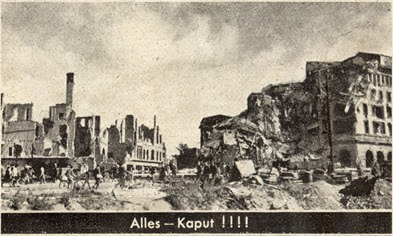

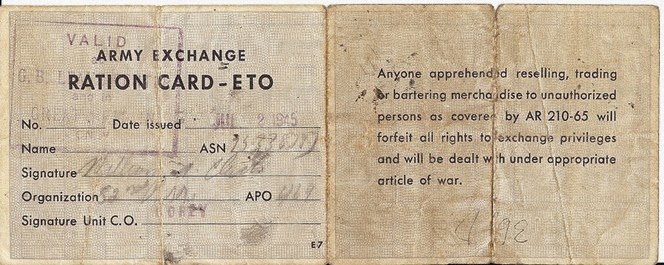

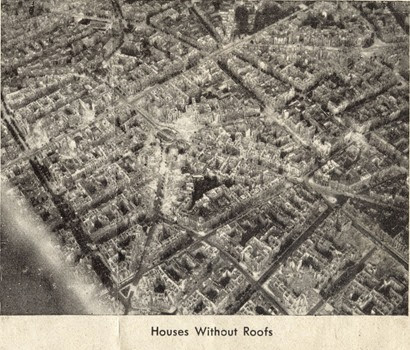

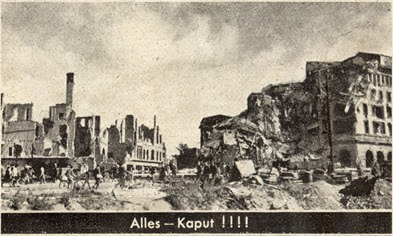

The long lice infested journey from Reims, France was finally at an end. As the train made its way into town, Bill leaned against the open door of the wooden boxcar, scanning the wreckage of destroyed buildings and craters in the streets of the once great German Capitol. Through his war jaded eyes Berlin bore all the wounds of a cataclysmic battle. It seemed that no structure was unscathed by the Allied air raids which left most buildings roofless or obliterated. Nearly all those still standing needed to be demolished. Avenging Soviet ground forces had completed the destruction. They had viciously mauled the fanatical Nazi defenders, utterly and literally smashing down the Third Reich’s last stronghold. Along the railway Bill saw desperate Germans stumbling about in confusion, pathetically clawing here and there, stooping to collect scraps of material, organizing piles of debris in futility. “The carnage of war” he mused to himself gazing at the devastation. The heady surge of unquenchable vengeance coursed through him again, engulfing his whole being. Over the years of war it had become an inescapable, automatic response and one he had come to embrace. “They had it comin’…” he murmured. “…And Ivan sure kicked the hell out of 'em”. Although it was undeniably worse compared the bombed out cities of Bonn and Cologne, Berlin’s ruination was a familiar scene for Bill. It gave him a certain comforting feeling and a growing sense of excitement. As he did in those cities, he was sure he would thrive in this hell hole. He thought to himself with giddy anticipation, “A guy could do whatever he wanted in a place like this”.

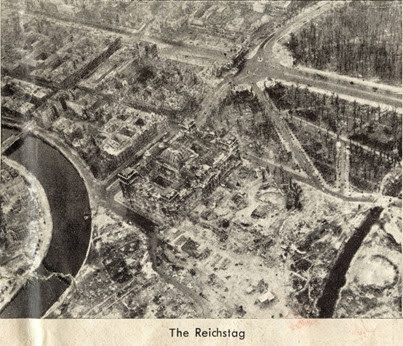

Photos 1 & 2: Aerial Photographs of Berlin in Ruins, circa July, 1945 Source: The 82nd Division Newspaper “‘The All American’ Paraglide, Berlin Edition, 82nd ‘All American’ Division” 1945 Author’s collection

Photo 3: Aerial view of Berlin prior to (left) and after (right) Allied bombing circa April 1945 Source: Fold3.com

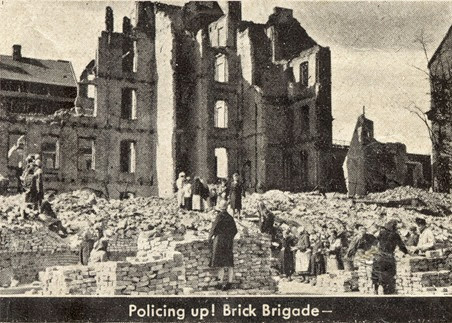

Photo 4: Berlin in ruins at ground level, circa July, 1945 Source: The 82nd Division Newspaper “‘The All American’ Paraglide, Berlin Edition, 82nd ‘All American’ Division” 1945 Author’s collection

In stark contrast to these pictures, Bill truly enjoyed his time in Berlin. Decades later he made the remark:

“Berlin… Now that was good living.” – Bill Clark, January 26, 2000

At first thought it might seem unnatural and macabre for anyone to derive enjoyment from such an experience, especially given the appalling condition of the city and its pitiable inhabitants. Indeed, some of Bill’s experiences in Berlin are humorous, while others are tragic, some terrifying, and there are a few that readers may find abhorrent. All are fascinating. They speak loudly of the personal price paid and consequent life long burdens that he and his fellow paratroopers had to bear after having lived through more than two years overseas at war; 316 days of it spent on the front lines, miraculously without meeting their own deaths, as they watched 19,586 of their buddies become casualties. Source of statistics: Anzuoni, R., “’I’m the 82nd Airborne Division!’: A History of the All American Division in World War II After Action Reports”, 2005, p. 351.

After surviving all of that hell, it was with a yearning heart that Bill volunteered for dangerous occupation duty in Berlin. To understand his excitement at the prospect, and to appreciate his Berlin experiences with an open mind, one must try to grasp the mentality of a soldier ravaged by war at a young, impressionable age. To get an inkling of that we need go no further than the postwar words spoken by the fellow paratroopers in his unit, the 82nd Parachute Maintenance Company (PMC):

“PARATROOPERS are lusty men. The men of our outfit were paratroopers. Quite without intent, we have suggested in picture, prose and verse, the healthy animal actions so pronounced in units overseas that are sent on dangerous missions. Most of us did not seek the company of the nice girls of Ireland, England and France. We sought the other kind, and what went with them: whiskey, illegitimate children and disease. The men of our outfit will remember this; the average layman may be horrified. Yet morals are lowered everywhere in time of war. Therefore, it is easier to understand how our young men, who normally would have been married (and some who already were), threw themselves into the stream of debauchery and drifted.

OUR BOYS didn’t see nearly as much combat as those of the line outfits. Yet we sent jumpers on every major operation from Sicily to Holland. We are especially proud of this when it is considered that we didn’t have the preliminary training of the linesman and still hurtled down on the enemy with the best of them.

ONE WORD about our dead. When their broken bodies lay bleeding on the ground, when the word came back that one of us had given all, the cursing, laughter, vulgar remarks and horseplay ceased. This tribute to the departed was written on silent faces: There died a better man than I.” Source: Embry, W., (Editor) “The Story of the Parachute Riggers of the 82nd Airborne Division” circa August, 1945 Unpublished Manuscript , p. 1 Author’s collection

Berlin in the Aftermath of the Potsdam Conference

The division of Postwar Germany among the Allied powers of France, England, America, and the Soviet Union was decided during the Potsdam Conference of July 17 – August 2, 1945. Berlin, situated firmly in the Soviet controlled East Germany, was very much isolated from the Western Allies in their administrative sectors of West Germany. The city was a microcosm reflecting these larger national scale divisions of territory. As such it was destined to become a political powder keg. With no common Nazi enemy left to fight, ideological differences between the Western Allies and the USSR boiled to the surface. It was in Berlin that these differences were most apparent.

Map 1: Berlin Sectors of Occupation with Tempelhof Airdrome and the Berlin Black Market indicated.

Tempelhof Airdrome

Bill’s outfit, the 82nd PMC, was based at Tempelhof Airdrome. At three quarts of a mile wide, it made a gigantic vacant hole in the surrounding cityscape. From the sky it resembled the Great Red Spot on Jupiter. It was to become a crucial strategic asset for the Western Allies during the Berlin Airlift. The Soviets coveted Tempelhof for its grandeur, but more importantly for its logistical value. At less than three miles away, its proximity the Soviet sector was a temptation for them.

As occupiers of the airport, possession of Tempelhof gave the Americans another distinct advantage. As a show of strength in the coming months they planned a schedule of airborne drops on the Airdrome. The size of Tempelhof made it feasible to drop whole regiments in a single stroke. Parachute jumps and glide-borne landings were planned for units organic to the 82nd Airborne Division including the 504 and 505 PIRs as well as the 325 GIR. The frequent sight of masses of paratroopers descending in broad daylight would help to ensure the Soviets didn’t underestimate the postwar military might of America and attempt an invasion of the airdrome.

Photo 5: An aerial view of Tempelhof Airdrome, in Berlin, Germany showing terminal buildings, landing area and central hangars. circa March 1945 Source: Fold3.com

Map 2: A close up view of Tempelhof Airdrome (now Tempelhof Park) and immediate environs

Bill’s First Duty in Berlin: Parachute Rigging and Maintenance

Immediately upon their arrival in Berlin, the 82nd PMC riggers set to work:

…[The men of the 82nd PMC] arrived… at Berlin, 12.8k 7 Nord de Guerre, Germany, which was Templehof (sic) Airfield in the heart of Berlin”. Source: Author Unknown, “82nd Airborne Division: 82nd Parachute Maintenance Company” Section 1 Unit History, Date unknown, p. 15

In a very short time the 82nd PMC achieved success on two main tasks. The first was the manufacture of a large number of accoutrements for the 82ns Honor Guard patrol uniforms:

“The maintenance section had another order for 14,000 scarfs and 4,000 more caps, even before the equipment was unloaded [at Tempelhof Airdrome]. After finding enough material for the required products, and setting up the maintenance shop the work was completed in record time”. Source: Ibid.

The second task entailed training of enlisted men newly assigned to the 82nd PMC from the 17th Airborne Division in maintenance and packing of parachutes. There were so many of these unqualified riggers that significant organizational measures were implemented:

“During this time the packing section unpacked as quickly as possible and organized their packing essentials. August 25th they started packing chutes. Because many of the men were not qualified packers, a packing school was organized in the Company to train these men”. Source: Ibid.

Photo 6: Tempelhof Airdrome Terminal Building. The hangars in front of the terminal were used by the 82nd PMC. Photograph taken July, 1945 Photographer: Cort W. Best Source: Fold3.com

There were many parachute drops at Tempelhof while Bill was in Berlin. The 82nd had a surplus of packed parachutes from their time at Camp Moaning Meadows, near Reims, France. Still more were needed:

“Packing for several jumps and for the Division jump school, 3,000 mains and 1,000 reserves were packed by September 13th”. Source: Ibid.

The objective of most training jumps were to keep the men at peak combat readiness, while simultaneously engendering respect on the part of nearby Soviet forces for the power of the Western Allies. Other drops were made to train the men in maneuvers for formal Division reviews.

General Gavin described the latter type in detail in a letter to his daughter dated August 30, 1945:

“This morning in about another hour, I am having Gen. Dwight Eisenhower and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee as our guests for an airborne division review. It is a very interesting affair that we have worked up. The troops walk by in review as they would land, with the artillery of the parachute battalions hand-drawn, etc. As the last man passes the reviewing stand, the first gliders pass overhead, they cut loose and land to the left of the reviewing party, they open and armed jeeps and motorcycles emerge together and pass in review. As the last vehicle passes in review, the first parachute transports appear in formation overhead and to the front. They jump in front of the reviewing party. As the last paratroopers land, the troop carrier pilots fly by “on the deck,” passing in review before the reviewing party.

Quite a deal but very difficult to coordinate properly. We have tried it once and it worked OK. I’m sweating out this morning. Friday I have the same thing for about fifteen Russian generals, I’m sweating out the toasts that follow that one”. Source: Gavin - Fauntleroy, B. “The General & His Daughter: The wartime letters of General James M. Gavin to his Daughter Barbara”, 2007, p. 192.

In this letter, General Gavin mentioned three of these reviews. The one for General Eisenhower as well as the other in front of the fifteen Soviet generals which included the famous Marshal Georgy Zhukov have been recorded elsewhere; and it is likely there were more. Source: Booth, T., “Paratrooper: The Life of General James M. Gavin”, 1994, p. 309

Photo 7: General Eisenhower and Soviet General Zhukov salute the 82nd Honor Guard. Source: The 82nd Division Newspaper “‘The All American’ Paraglide, Berlin Edition, 82nd ‘All American’ Division” 1945 Author’s collection

The complex intricacies of these displays would have necessitated several practice exercises or “dry runs” to ensure they went off without any mistakes or accidents.

The Parachute Accident

However, accidents did occur and there was one in particular which Bill spoke of in detail. His sister remembered that it happened in Berlin probably in a training jump in preparation for a Division review. Bill watched as the planes were coming in to drop their cargo of paratroopers over Tempelhof Airdrome. Soon the sky was filled with silk. It was a beautiful site. The awesome spectacle of so many chutes in the air never failed to amaze even the most hardened veterans. Bill looked on with pride in the Division. A crowd of personnel had gathered to watch the spectacle. They were cheering and waving at the paratroopers.

Then tragedy struck. One of the white streamers of silk failed to open. It flickered like a candle’s flame in the sky as its human cargo plummeted straight through the formation before hitting the ground with an audible thud not too far from Bill’s position. For some unknown reason the reserve chute had not been deployed. His heart sank as the trooper fell from his place in heaven. Those watching the event let out moans of horror. A medical unit was already on its way to check the trooper’s condition. Bill ran over. When he got there the medic was checking the body for a pulse, but it was obvious the man was dead – his insides undoubtedly had been scrambled on impact and his bones had been shattered. The Division chaplain was running over too with a group of officers.

Working on instinct, Bill read the serial number on the side of the chute sack and ran back to the packing hangar. In the commotion no one noticed him. He entered the unguarded room which held all of the chute packing records and retrieved the 4 x 6 card with the details of who packed the dead trooper’s parachute. He glanced at the name of the man on the card and recognized it.

Bill screamed inside. A man in his prime had just died and the war was over. There was no enemy left to fight. It was an outrage. Thinking quickly he realized there was one thing he could do to prevent further repercussions of injustice. He knew the brass would need answers. Their would be trouble for the rigger who had packed the failed chute. Bill grabbed 5 or 6 cards on either side of the card in his hand. Taking out his Zippo lighter he set the cards on fire, throwing them into a nearby trash can. He watched to make sure they completely burned. The smell of burnt paper was quickly dispelled in the well ventilated hangar. As calmly as he could he walked out of the room housing the records and moved out of the entrance of the hangar to where the crowd had gathered and melded into it.

A few minutes later some men were sent in to retrieve the card. They needed to know who had packed the chute. When they couldn’t find the card they rounded up all the packing supervisors to ask them where it was. A disciplinary review ensued. Bill and the other riggers were questioned. They closed ranks, knowing that the less they said about the incident increased the chances that justice would be served. Nothing conclusive was turned up. When it was over Bill took an oath never to tell a living soul whose name was on the card.

Patrol duty

Along with their usual duties the men of all of 82nd Airborne units were assigned to patrol and/or guard duty. This was true for the 82nd PMC which besides parachute rigging and repair duties, made patrols around the American sector.

“I know he was rigging parachutes in Berlin and showed me how to tie a simple knot that wouldn't unravel which I still use in sewing. In addition to this he made patrols”. Source: Interview with Bill’s sister Doris, March 26, 2006

Upon their arrival in Berlin the men were given an orientation:

“Part of our first day in Berlin was taken up with orientation – the things to do and not to do”. Source: Edwin R. Bayley as quoted in Nordyke, P. “More than Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” 2008, p. 402

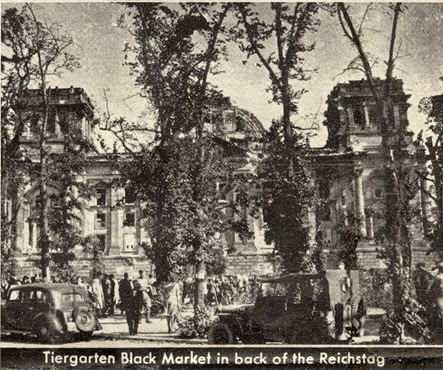

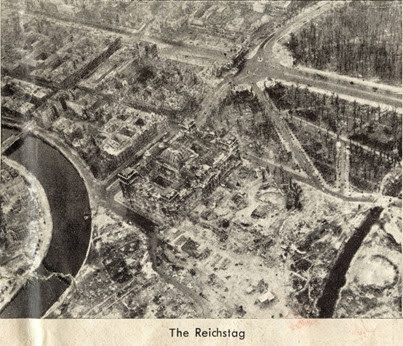

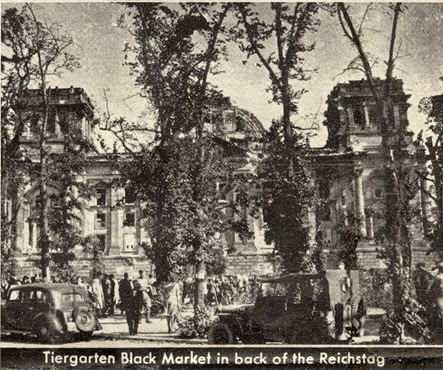

They were lectured about their duties and the dangers of occupying Berlin. They were not to fraternize with any Germans and to do so would lead to a court martial. Another offense punishable by court martial was any involvement in black-marketeering. A black market had already been established in the British controlled Tiergarten, behind the Reichstag building. The men were cautioned that no leniency would be given to anyone caught trading there.

When assigned to patrol the men worked in teams of two and were ordered to never split up. Each patrolman was armed with an M1 Garand rifle, and a knife. Sergeants and officers also carried a Colt .45 caliber pistol. Off duty personnel were forbidden from carrying any firearms and if caught they faced a court martial.

The men were informed of the delicate relations they maintained with the Soviets. An uneasy peace existed between the Soviets and the Western Allies. After the horrendous price they had paid during the barbarous the Nazi offensives, Stalin believed that his Red Army should occupy all of Berlin; that the Western Allies had no claim to it. He had only reluctantly shared it with the Americans, British and French by agreeing to break the city into four sectors, one for each of the major powers. To defend their respective sectors, the city was crammed with soldiers of all four sides.

A number of the experienced 82nd men had volunteered for duty in Berlin. They were well armed and accustomed to killing. Many of them loved it. Hardened veterans like these could have easily been carried away with the unfettered passion of occupation duty. Two years of living to kill had left them keyed up for a fight that no longer existed. The Soviet soldiers were different. They were untrained, poorly disciplined rear echelon troops. After having not been paid wages in years these desperate men had earned the dubious reputation of looting, which inevitably led to the rape, beating and even murder of Berlin civilians. The Western Allied troops regarded the Soviets as crazy and out of control. On both sides there was an abundant stream of alcohol, women, booty and guns – a powerful and volatile mix. The men were forewarned to remain disciplined and not be swept away by the siren song of postwar spoils.

The orientation talk included practical aspects of dealing with the Soviet troops. They could not be trusted under any circumstances. Soviet soldiers had been commonly encountered in the Allied sectors searching for booty and women. The Soviet hierarchy had given General Gavin, the administrator of the American sector, its assurances that this practice would cease. Despite that, incursions into the American sector by armed bands of drunken Soviets had continued unabated. While on patrol, men encountering them were to be cordial and lethal force was only authorized if their lives were threatened. If a Soviet was witnessed in the act of a heinous crime, the men were ordered to look the other way and in no circumstances were they to intervene. To do so was another offense punishable by court martial. Off duty personnel were advised to never travel alone and to stay clear of any Read Army troops they may see.

Encounters with former SS and Hitler Youth in their capacity as “Werewolves” had been anticipated possibilities. The “Werwolf” was a guerrilla movement formed mainly of Hitler Youth and former SS personnel sworn to wreak havoc and destruction in a defeated postwar Germany. At the time little was known of their distribution, strength or capabilities, but Berlin was judged as a credible hotbed of activity due to the high numbers of Hitler Youth reported by the Red Army in their battle to take the city. Any Werewolves were to be captured for interrogation and killed only if they attempted to escape. The insignia of the Werwolf had been discovered inscribed on walls around the city and was a sign that they had recently been active. It was in the form of silhouetted man wearing a trench coat and hat, known as ‘the sign of the dark men’ Source: Biddiscombe, P., “Werwolf!: The History of the National Socialist Guerrilla Movement 1944 – 1946”, 1998, photographic section p. XXVII.

America’s Guard of Honor

The 82nd Airborne maintained an honor guard while in Berlin. The honor guard uniform used consisted of white gloves; a matching white belt around the waist of the Ike jacket; a golden lanyard hung over the right shoulder; a silk scarf made out of white parachute silk was tucked around the neck; and a garrison cap with smart looking piping topped it off. The classy ensemble included an M1 Garand rifle, with shiny lacquered wood, a polished barrel with a gleaming chrome dipped bayonet attached. It looked sharp and impressed Bill very much. He talked about it for years afterward. In his role as a rigger, Bill may have been among those charged with manufacturing the uniforms used by the guard. All of the men chosen for honor guard duty were at least 6 feet tall, so at 5’ 7”, Bill was excluded. Men of appropriate height were chosen from each company to march in the honor guard on a rotation basis. General Patton commented that the 82nd honor guard in Berlin was the best he had ever seen. They were so good that the Division quickly became known as “America’s Guard of Honor”, a title still in use today.

Photo 8: The 82nd Airborne Honor Guard at Kammergericht, Berlin, circa August, 1945 Source: The 82nd Division Newspaper “‘The All American’ Paraglide, Berlin Edition, 82nd ‘All American’ Division” 1945 Author’s collection

“Werwolf”: The Postwar Nazi Resistance Movement

Dangers of Night Patrols

Bill said that they always patrolled in pairs and that night patrols were particularly dangerous, frightening experiences. He would patrol an area at night only to see the next morning new signs of the Werwolf’s ‘dark men’ etched using charcoal onto fences and buildings, in the exact same place he had patrolled just hours before. Sometimes these signs were found outside of the very buildings Americans were quartered. This was a clear sign that there was an underground resistance movement present in Berlin, even during this relatively late postwar period.

In fact, organized Nazi resistance groups continued their activities in Berlin well into 1947. Source: Biddiscombe, P., “The Last Nazis: SS Werewolf Guerrilla Resistance in Europe 1944 – 1947”, 2004, p. 190.

Photo 9: A likely patrol beat. Destruction in a Berlin street located just off of the Unter den Linden "Under the Lime Trees" (a major arterial road in Berlin) July 3, 1945 Source: No 5 UK Army Film & Photographic Unit, Wilkes A (Sergeant) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Indeed other reports by veterans have corroborated the presence of postwar Nazi guerillas active in Berlin during the Allied occupation:

“We were required to carry weapons and to travel in pairs, because the German youth still wouldn’t accept the fact they had lost the war. If a soldier was caught alone he might be attacked and killed. Some of the bodies of Allied soldiers were found in canals, where they had been dumped after being killed”. Source: Plebanek, Frank. A., “18 Months in ‘E’ Company, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment” as quoted in Nordyke, P. “All American All The Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II” 2005, p. 764.

Attacks by Dogs

Bill also shared other evidence of guerilla warfare in the form of German military guard dogs left behind which were somehow programmed to attack American soldiers. He thought it seemed that handlers were still directing them but if not that, then the dogs were still following former training because they were intent on attack. The only defense was to shoot them and he said he had to do that several times. He never liked dogs after that although he was the one who cared for most and enjoyed the farm dogs before he enlisted in the Army.

Bill said that the former German police force was being employed in the American sector of Berlin to help keep the piece. When these German police patrolled, they usually did so with Alsatian guard dogs. In one incident in particular, Bill said he was walking past a police officer and his dog when the dog began growling at him and barking loudly. It looked as if an attack from the dog was imminent. Bill drew his Colt .45 pistol and aimed. The policeman waved his arms and pleaded to Bill not to shoot his dog. The dog did not back down and was beginning to pounce at him. As it launched its attack, he pulled the trigger and shot it dead. Curiously, the policeman became very upset and wept over the dog’s dead body.

Caught off Guard – Bill’s Encounter with Postwar Nazis

Bill did have an encounter with what he concluded was a Nazi guerilla fighter, but it was not on a patrol. It happened off duty while enjoying the nightlife in Berlin. The city’s nightclubs were in full swing at the time and even after Paris he was more than surprised at the entertainment available in them. He didn't go into details, but he was in awe at what they offered. When visiting these places fraternization with German women was an inevitability. Even though fraternization was forbidden it was impossible to enforce as the following 82nd veteran’s account clearly illustrates:

“We were each issued three condoms and an emergency prophylactic kit. The condoms were to be used if one fraternized, and the kit was to be used if one did not use a condom. If a military policeman or an officer stopped a soldier and one of the three condoms or prophylactic kit was missing or used, this was a criminal offense subject to court-martial and possible confinement. Obviously, with thousands of soldiers and hundreds of thousands of lonesome girls and women not having any sexual contact for a long time or ever, this was a no-win situation. There was no way that fraternization and sexual activity could be prevented. The results were predictable for both officers and enlisted personnel – venereal disease for some, pregnancies for others, and lots of fun and amusement, and in some cases eventual marriage for others”. Source: Edwin R. Bayley as quoted in Nordyke, P. “More than Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” 2008, pp. 402- 403

When on patrol or guard duty the paratroopers were armed with M1 Garand rifles and pistols for sergeants and officers. Orders were issued that firearms were not to be carried while off duty. The Soviets had no such restriction making it particularly dangerous to go anywhere without a weapon. Bill said that when off duty he always carried his standard issue Colt .45 pistol, cleverly concealed in a special pocket he had sewn into his jacket. He said it was foolhardy not to carry a firearm for protection. Other men did the same. In some cases they were caught and tried for the offense:

“An H Company [504 PIR] man was arrested by the MPs for carrying a concealed weapon. At his summary court trial he demonstrated that the Colt .45 caliber pistol, which he had been charged with carrying, was not operable. He had removed the firing pin, which he produced as evidence. He did not, therefore, believe he was carrying a real weapon. He intended to deliver the pistol to a friend scheduled to leave soon for the States. The court ruled against him, saying that even though the pistol lacked a firing pin, it could still be looked upon as a weapon”. Source: Megellas, J., “All The Way To Berlin: A Paratrooper at War in Europe”, 2003, p. 279.

Like virtually all men, Bill fell prey to the allure of the Berlin nightlife. On one night it had almost cost him his life. After a lot of alcohol and dancing Bill found himself drunk and in the arms of a woman who led him to a nearby partially damaged building which was being used as a bordello. Leaving the raging nightclub behind, Bill followed her up a flight of stairs and into the first room directly in front of the landing. She opened the door to a spacious chamber with a large bed. She lit an oil lamp which burned softly in a corner casting long shadows across the room. Along the entire length of the exterior wall hung a thick velvet curtain used to protect against the cold from the shattered windows behind. It moved ever so slightly in the Indian Summer night’s breeze.

Bill sat down on the edge of the bed facing the curtains, unlaced his jump boots and took off his uniform. After they were finished he dressed quickly. Once more he sat down on the edge of the bed and was lacing up his jump boots when something caught his eye. The toes of a pair of boots were sticking out from behind the curtains. In his drunken state, he wasn’t sure whether or not they were there when he had unlaced his boots.

Nevertheless a charge of adrenalin coursed through his veins. He rose to his feet and quickly made for the door. His left hand opened the door while his right retrieved his Colt .45 pistol from the hidden pocket he’d rigged into his jacket. He closed the door behind him and headed for the stairwell.

He was partway down the stairs when the door suddenly swung open. A man’s voice shouted something at him in German. Turning around Bill saw a man dressed in street clothes preparing to fire a German Luger pistol at him. It was obvious to Bill that his intent was not to rob, but to kill. Before the German had a chance to shoot, Bill aimed and pulled the trigger on his Colt .45. Drunk and in a state of surprise, fear took the reins. He kept firing until the weapon was empty. The man was propelled backwards by the bullets which left a great hole in his chest the size of a softball. The body fell backwards and hit the floor.

Bill turned and raced down the stairs cursing his bad judgment. How could he have been so stupid to trust a Nazi woman and follow her drunk to a place of ambush? Why didn’t he have the sense to check the curtains beforehand? Only God knew how many others were still up there and he didn’t have a reserve ammo clip. Filled with terror, he ran all the way back to the barracks resolving never to leave again without extra ammo. Berlin had shaped up to be a much more dangerous place than he had considered when he first volunteered for occupation duty.

It is more than interesting to note that Nazi resistance groups are documented to have been active in the American sector, in the Neukolln borough, less than a mile away from Bill’s barracks at Tempelhof Airdrome:

“…small scale Nazi resistance activities in Neukolln continued to percolate even after the arrival of American occupation troops in July 1945, when the borough became part of the US sector of Berlin. In March 1946, American authorities reported that they had ‘a number of… suspected groups under surveillance’, and that arrests would be made upon the termination of investigations. Later that year, ‘a gang of young troublemakers’ was busy terrorizing members of the ‘Victims of Fascism’ movement, and pro-Nazi leaflets were reported to be circulating at the borough magistrate offices”. Source: Biddiscombe, P., “The Last Nazis: SS Werewolf Guerrilla Resistance in Europe 1944 – 1947”, 2004, p. 190.

Could Bill have encountered a member of one these same Nazi resistance groups? Were they Werewolves? These questions remain open, but he undoubtedly killed a German man that night whom he was certain was a postwar Nazi resistance fighter.

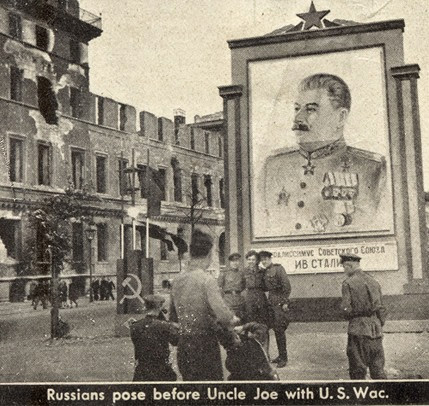

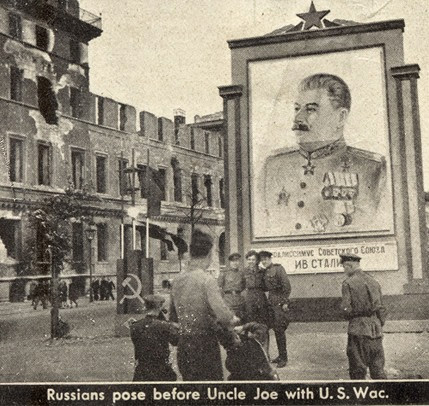

Of the Soviets: “I must tell you, however, the men who follow us are pigs.” - unknown Soviet Lieutenant, circa May, 1945

“Berliners were sometimes surprised by the discipline, even the kindness, of frontline Red Army veterans. They did not act like barbarians but stopped to befriend children or share a glass of wine with adults. ‘I must tell you, however,’ a Soviet lieutenant warned the mother superior of a convent, ‘the men who follow us are pigs.’

Though the lieutenant’s comrades were no angels, he was right about many of those who arrived later to occupy the city: Women were raped by the tens of thousands; neither the very young nor the elderly were spared. Hundreds of Russians got drunk and roamed the streets. One band of soldiers raided a film-studio costume department and cavorted through the city wearing Napoleonic hats and 19th Century skirts, and firing their weapons into the air.” Source: Simons, G. (Ed.) “Victory in Europe: World War II”, Time-Life Books, 1982, p. 158

Photo 10: Soviet soldiers pose in front of a mural to Stalin circa October – November, 1945 after armed Soviet incursions into the American Sector were halted. Source: The 82nd Division Newspaper “‘The All American’ Paraglide, Berlin Edition, 82nd ‘All American’ Division” 1945 Author’s collection

The 82nd Airborne Meet the Soviets in Lethal Confrontations

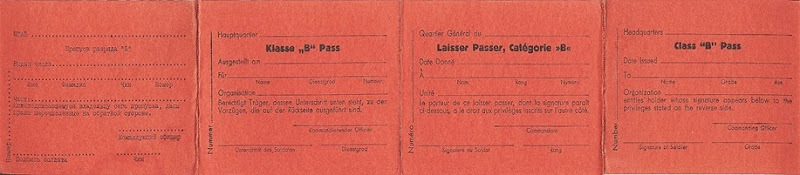

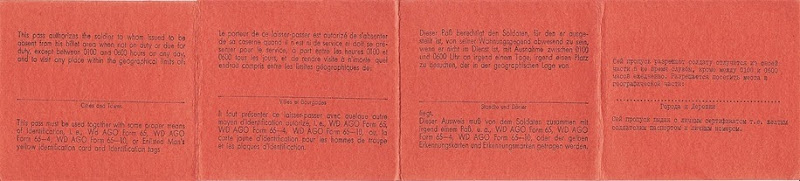

After the Potsdam agreement, Allied soldiers of all nations were allowed to visit all other Berlin sectors. In practice, the Allied soldiers of Britain, France, and America were able to freely visit each other’s sectors at will. However, the Americans were under orders not to visit the Soviet sector without permission. If caught there they faced disciplinary action from the US Army. Source: McKenzie, J., “On Time on target: The World War II Memoir of a Paratrooper in the 82d Airborne.” 2000, pp. 186.

For their part the Soviets had installed roadblocks and had taken means to discourage Allied soldiers from entering their sector. Furthermore, they instituted a double standard by allowing Soviet soldiers to enter any other sector at will and to carry weapons when the did so. Source: Nordyke, P. “All American All The Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II” 2005, p. 763.

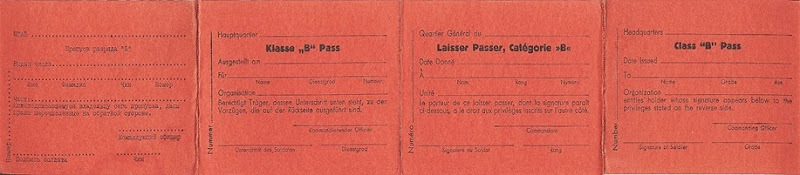

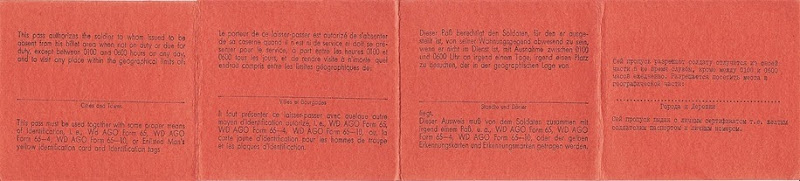

Photos 11 & 12: One of Bill’s Unused Class “B” Passes written in English, French, German, and Russian. Theoretically required for entry into other Allied sectors Source: Author’s Collection (Click on them to read in higher resolution)

In the first month of occupation, gangs of Red Army occupation troops roamed across Berlin as they had before the 82nd Airborne had arrived in the city. They had been in the habit of raping women, looting property, and murdering civilians if they resisted. The new Potsdam accord of dividing the city into Allied administrative sectors meant nothing to them. Their depraved orgy continued unabated with raids into the American and other Allied sectors. Road blocks were put up at entry points into the American sector in an attempt to curb these incursions. The Soviet soldiers ignored them. Instead of stopping at checkpoints, the fired their weapons. Being combat soldiers, the paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne did not meet such blatant disregard for their authority with impotence. They took action which resulted in at least 20 Red Army troops killed in the first month of occupation. Source: Ibid.

During this time the drunken bands of Soviets sometimes liked to play a game reminiscent of an American “old west” main street gunfighter shootout. When they came across patrols of 82nd men in the American sector they would draw their weapons and take aim at the paratroopers. Not being able to speak Russian, the Americans could not tell whether they were joking or if these were real challenges. Unwilling to take the risk, and being trained to make split second life and death decisions, the veteran paratroopers invariably drew their weapons and killed the Soviets without hesitation. Source: McKenzie, J., “On Time on target: The World War II Memoir of a Paratrooper in the 82d Airborne.” 2000, pp. 187.

Written accounts of the Soviet occupation force in Berlin describe them committing graphic atrocities, brazen looting, and of having a complete disregard for their own personal safety. John McKenzie a replacement who first jumped with the 82nd Airborne into Normandy, despite having accumulated sufficient points, had volunteered for Berlin duty.

As a sergeant of the guard McKenzie was placed in charge of a 59 man detail guarding the Steglitz railway station on every third day. Steglitz station was the first railway stop in the American sector for trains coming from the Soviet sector. Every day the trains were packed with refugees escaping the comparatively pitiful conditions they had endured in East Berlin. Most of them were old and young people, and women. Before they left East Berlin, these train passengers were searched by Red Army soldiers who stripped them of anything of even meager value. The Soviets inspected their victims’ mouths. Using pliers which they always carried, they painfully wrenched out any teeth containing gold fillings. If a person verbally protested they were either severely beaten, or murdered. Source: McKenzie, J., “On Time on target: The World War II Memoir of a Paratrooper in the 82d Airborne.” 2000, pp. 192 – 197

Taking advantage of the rule that all Allied soldiers on occupation duty could visit any sector in Berlin, regardless of their nationality; Soviet soldiers did not stop their “inspections” of trains bound for the American sector at the border. They continued their cruel and grisly methods of wealth generation into the American sector. Under the law of occupation at the time, the 82nd Airborne (indeed all Allied occupation forces) was under orders not to challenge any Allied soldiers regardless of their behavior. This was the law even if it meant witnessing a Red Army soldier raping or murdering an old woman. Under no circumstances were 82nd paratroopers to intervene. As the days passed the Soviets took advantage of this and became increasingly brazen in their immoral conduct. The paratroopers from privates, corporals, sergeants, and officers, on up the chain of command complained vigorously about the intolerability of the situation. Finally, after a week of listening to the complaints, the Commandant of the American sector, General Gavin himself, decided to take action. He personally toured Steglitz station and was appalled as he witnessed the Soviets at their horrific game. It so angered him that he pursued some of them trying to get back to their sector. As the criminals fled, Gavin drew his pistol to shoot them. He would have done so, but was restrained by his men. Not only did the inhumane acts of the Soviets anger the General, the fact that they carried them out in Steglitz station plainly showed they had no regard for American authority in the American sector. Source: Ibid.

General Gavin stormed off, determined to put an end to the brutality. A few days later the 82nd Airborne’s orders were changed. From then on if an Allied soldier of any nationality was found by a guard or patrolman assaulting civilians, he was ordered to challenge and make an arrest. If the offender failed to stop or fled, a warning shot would be fired. At that point if he did not surrender, the soldier was ordered to shoot to kill. Source: Ibid.

The brutality of the Soviets toward the Berlin civilians was not restricted to railway stations. They occurred across the American sector and were even directed at 82nd Airborne personnel. In one incident it was reported that 30 Soviet troops had killed a paratrooper near to a theater. Source: Nordyke, P. “All American All The Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II” 2005, p. 764.

In the ensuing days many Soviet soldiers were killed by 82nd troopers until they learned to respect their authority and stopped harming civilians in the American sector.

Bill’s Observations of the Soviet Occupation Troops

While on patrol and during his free time Bill was given firsthand insight into the mentality of the Soviet occupation troops. In his observation, they were slovenly drunks with no respect for themselves, those around them, nor even the equipment they relied upon for their survival. Bill said that they would think nothing of raping women in the middle of streets in broad daylight. Trucks would pull up in front of houses and Soviet soldiers would pile out to systematically loot whole neighborhoods.

In Bill’s mind, the worst thing about these incidents was that they had happened in the American sector and the Americans were powerless for a time to do anything about it. He said that as the loot ran out in their sector, Soviets had with increased frequency conducted armed raids into the American sector to rape and pillage with impunity. If a trooper was caught killing a Soviet, even under these circumstances, a court martial was the penalty and it would have been enforced.

The Spree River cuts through Berlin and during the occupation it separated the Soviets from the Americans, the British and the French in their respective sectors of the city. On a few occasions, Bill said he and some other men visited an area of river front which separated the Soviet and American sectors to take a look at the Red Army troops on the other side. From the American side of the Spree, they could get a good clear view into the Soviet side. On one visit, Bill said a large number of Soviets with vehicles had gathered together at the base of an embankment on their side which had been made muddy from a rain shower. All of them were drunk. Bill and his friends decided to watch them. The Soviets began driving their trucks and cars up and down the embankment apparently in a game of “smash up derby”. They would gain speed and ram into one another’s vehicles seemingly for the fun of it. By the sound of the crunching gears and lugging engines they also had no clue of how to drive. Some of them were hurt in the crashes. In a few cases it appeared they had sustained life threatening injuries. It was a sloppy display of completely undisciplined troops.

Ever since he’d arrived in Berlin Bill had observed an inordinate number of broken down Soviet jeeps, troop carriers and the like scattered around. Being mechanically inclined, every now and then he stopped to inspect one. Expecting to see major damage such as a broken axle or a cracked engine manifold, he was a little surprised to see that many of them only had flat tires, or had run out of radiator water. He had wondered why the Soviets wouldn’t fix these simple problems instead of wasting a valuable resource. Later, in light of the spectacle of degeneracy at the river embankment, the abandoned vehicles began to make more sense. It stood to reason that they would drive them until they broke down. They simply had no respect for their equipment and no idea of how to maintain it, nor use it.

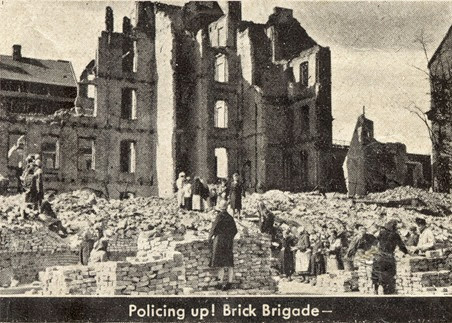

During Bill’s day patrols, the German civilians would come out onto the streets and were busy going about their tasks. Some were organizing and cleaning the debris. Others were washing clothes next to communal water pumps or repairing what they could with the meager tools and supplies at hand. All of the people he and his patrol partner saw were working including very young children whose faces all bore the same sad expression of shattered innocence. It was a look Bill had seen all over occupied Germany. Like the other conquered Germans he’d encountered the people of the city were wary of the paratroopers, intimidated by their smart uniforms and weapons.

Photo 13: So called “Rubble Women” work to clear debris in a Berlin suburb. These German women worked in organized teams all across postwar Germany to restore order to towns and cities shattered by aerial and ground bombardment. Source: The 82nd Division Newspaper “‘The All American’ Paraglide, Berlin Edition, 82nd ‘All American’ Division” 1945 Author’s collection

The behavior of the Berliners Bill had seen while on patrols stood in contrast to the Soviets destructive and wasteful attitude to valuable resources. Not that Bill was prone to empathizing with the German plight in Berlin. Quite the opposite. He was disgusted by them, after all the destruction and exploitation he had seen the Nazi’s perpetrate against innocent people. However, he was convinced that the Allied forces could have and should have pushed the Soviets back into Russia. His observations of the how the undisciplined Red Army troops mistreated themselves and their vehicles was telling. Because of this he thought that they could not have fought a mechanized war and therefore could have been beaten, thus avoiding the looming Cold War. He may have never known that the Soviets occupying Berlin were in fact rear echelon troops. Unlike the front line Red Army units which had driven the Germans back across Eastern Europe and captured Berlin, the occupiers of East Berlin were poorly trained, and had no combat experience. Perhaps his opinion may have changed if he had been able to observe the original Soviet conquerors of Berlin.

Bill’s Soviet Encounter

Sometime in the 82nd Airborne’s tenure in Berlin, Bill and a buddy had an encounter they would never forget. One day while on a patrol they were captured and kidnapped by Soviets. It is a story of survival to which I have found no precedent in any of the 82nd Airborne literature of first hand veteran accounts, nor any works of derivative research. It is unknown exactly where these events took place, although they must have started somewhere in the American sector. What is also uncertain is what prompted the capture and kidnapping.

All paratroopers took a dim view of the various atrocities committed by the Soviets, but the most disdainful was rape and murder. For these crimes, paratroopers had to fight the urge to step in and stop the act. One possibility is that Bill and buddy intervened in a Soviet looting raid. However, it is more likely that they were running to the defense or aid of a female being raped, or a civilian being beaten, or one about to be murdered.

While it is unknown precisely when these events took place, it is likely that they occurred after the new rules were enforced, which enabled 82nd troopers to take action in cases of looting, assault, murder, and rape. Prior to this time, the Americans were not allowed to intervene in any wrong doing on the part of Soviets, no matter how grievous. Indeed it was a court martial offense to do so. As mentioned earlier, the new rules required that if a soldier on patrol found an Allied soldier of any nationality assaulting civilians, he was ordered to challenge and make an arrest. If the offender failed to stop or fled, a warning shot would be fired. At that point if he did not surrender, the guard or patrolman was ordered to shoot to kill.

It is my belief that Bill and his fellow patrolman came upon a criminal act in progress being perpetrated by a group of Soviets in the American sector. In this most likely of scenarios, when challenged, they failed to stop, and instead of fleeing the scene, the Soviets outnumbering the two man American patrol, turned the tables and counter-challenged them. Outgunned, Bill and his partner were forced to drop their weapons and surrender to the Soviets.

When Bill told the story he said they were captured and quickly marched out of the American sector and into the Soviet sector where they entered a bomb damaged house and were led through one room and into another. There were no windows in the room and the only exit was through the the front door via the room from which they had entered. Bill could make out the remains of a stairway leading upwards. It was impassable, choked with debris from the floor above. Another doorway led back further into the building presumably to the kitchen, but it too was filled with bricks, boards and plaster from a cave in.

The Soviets stayed with them in the room and started drinking. Bill said they were not drinking vodka – the standard drink issued to all Red Army troops. Instead it was kerosene of all things. He said that the odor of it on their breath was unmistakable. Their captors offered him and his partner a drink of it, but they both refused. This appeared to anger them. After a while the drunken Soviets all got up and speaking incoherently, they stumbled through the door. The last one to leave, closed it. The sound of a dead bolt could be heard sliding though its loops, locking Bill and and his partner in the room. For the next hour or so the sounds of continued drinking and conversation could be heard coming from the other room as the Soviets imbibed more of the kerosene.

Bill had no idea of what their fate would be. However, it did not appear at point that they planned to kill them yet. Whomever their captors were, it seemed that they were awaiting an assessment from a higher authority to decide their future. Bill reasoned that if their lives were to be spared, it was possible that they might be exchanged for something the Soviets wanted from the Americans. Alternatively, perhaps frightened by the possibility of an escalation of the mutual animosity between the two Allies, the Soviets might have been planning to kill them and anonymously dump their bodies in their sector to avoid any unwanted scrutiny. The Soviet leadership attributed very little value to their individual soldiers. The Americans in contrast, valued each soldier much more highly. On the one hand if they did not return, the Americans might ask questions and upon discovering their fate, demand their safe return. On the other hand the Soviets could all too easily have disposed of them after a summary execution.

While all of this weighed on their minds they searched for a way to escape. As luck had it they found one. Bill noticed that above the door there was a transom. The thickness of a door, a transom is a 1 foot by 4 feet piece of wood set on a horizontal hinge above the top of a door frame. It usually has a full 90 degrees of movement either outwards or inwards. It is used to ventilate a room without having to leave doors open and has a supporting rod connected to a latching mechanism to hold it in place while open.

The pair waited for the Soviets to fall asleep before attempting a breakout. Bill’s buddy hoisted him up to look through the transom for any signs of conscious life. Finding only comatose drunks he took the transom off of the supporting rod that propped it open. It creaked loudly as it was lifted. He waited a few moments, but there was no reaction from any of the sleepers. Peering through, Bill had a good view into the room. It was dark, but the coals from a fire cast their dying light across the room and with his dark adapted vision he was able to verify that all of the Soviets had passed out, sleeping deeply. Both men climbed up and one after the other slipped through the open transom.

As quietly as the creaking floors allowed, the pair made their way past the sleeping Soviets to the front door. Bill’s hand fumbled at the knob. It turned, but the door didn’t open. He frantically felt above it silently praying for a key to be in the deadlock. To his relief there was one. The key turned easily enough and the lock slid back. The door opened. They quickly checked for guards posted outside. Nobody was there and the street was deserted. With their hearts pumping madly the two began running full tilt, tracing their path back to their point of capture. A few minutes later they were back to the relative safety of the American lines. It wasn’t long before they met up with an American patrol and were nearly shot in a case of mistaken identity. But they lived to tell their tale and were never happier to be on the business end of an M1 Garand.

Berlin’s Black Market

Bill did not speak much about Berlin’s black market except to say that it was big and busy. Whatever dealings he had there he kept to himself. More than a few of the men did take part in black marketeering and racketeering in France and Germany. The latter part of the war and into the postwar period presented many tempting opportunities to make significant amounts of money given the desperation of Germans and the chronic shortage of basic necessities all across the European continent. Source: Embry, W., (Editor) “The Story of the Parachute Riggers of the 82nd Airborne Division” circa August, 1945 Unpublished Manuscript , p. 78 Author’s collection

Photo 14: Postwar Berlin’s vibrant Black Market was set up in the Tiergarten behind the battered Reichstag. Source: The 82nd Division Newspaper “‘The All American’ Paraglide, Berlin Edition, 82nd ‘All American’ Division” 1945 Author’s collection

The occupation currency in Berlin at the time was the Allied military German Mark. The Western Allies controlled the number of Marks available to French, British, and American service men. Americans could convert these Marks into US Dollars at a rate of 1 Mark to 1 Dollar.

For their part the Soviet troops always had plenty to spend because their authorities printed Marks without restriction and used them to pay their soldiers, many of whom had not been paid in years. The Red Army soldiers were forbidden to convert Marks into Soviet Rubles; so the only way for them to make money was to buy small valuable items such as watches and jewelry and sell them when they arrived back to the Soviet Union.

Photos 15 & 16: Bill brought home this German Occupation Mark in ½ Mark Denomination Source: Author’s Collection

Americans could send their Marks converted into dollars home for safe keeping by relatives. Once back in the States the money they had earned in Berlin was to prove very helpful in the depressed postwar economy. The remainder of the money not sent home was used for entertainment and alcohol in the Berlin nightclubs.

An average American soldier from other units was paid $17.00 per month. Paratroopers received the same base pay and a bonus “jump pay” of $55.00 per month in 1942 for the inherent hazards of parachuting behind enemy lines. Source: Mast, G., “To Be A Paratrooper”, 2007, p. 14

With the exception of heavy gamblers, given their high wages, almost all paratroopers were flush with cash even before they arrived in Berlin. Indeed, Bill had so much money that like most of the men he had his pay permanently deducted. Each month he sent a portion of it home to his family. In fact, the men had always been encouraged to send some of their money home.

In Berlin, the black market was so profitable, troopers were initially sending home upwards of 200 percent of their pay. This practice if allowed to continue would have quickly become untenable so a rule had been put in place that only allowed 110 percent of a trooper’s pay to be sent home. Resourceful men managed to find loop holes which enabled them to collude with a gambler or smoker who did not send much or any money home. For instance, for a fee a gambler could send a fellow trooper’s excess money home to the gambler's family who would then arrange for it to be forwarded to the trooper’s family. In this way men could send virtually all of their excess money home in amounts of thousands of dollars above their pay. Source: McKenzie, J., “On Time on target: The World War II Memoir of a Paratrooper in the 82d Airborne.” 2000, p. 190.

By the time the first units of the 82nd airborne arrived, Berlin’s black market was an established, thriving industry. On any given day and in obvious violation of Army regulations forbidding black-marketeering, Americans were soon seen everywhere with bags containing their goods. The customers included German civilians and Soviet soldiers.

Some troopers had large collections of wrist and pocket watches which they had liberated from surrendered German soldiers. These fortunate men made a lot of money. Watches sold for 100 – 250 Marks depending on quality. Mickey Mouse watches were in highest demand selling for as much as 1000 Marks. Source: Megellas, J., “All The Way To Berlin: A Paratrooper at War in Europe”, 2003, p. 282.

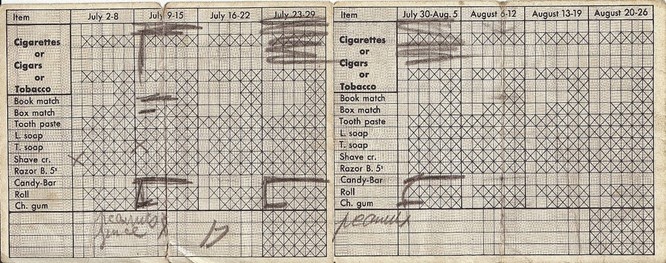

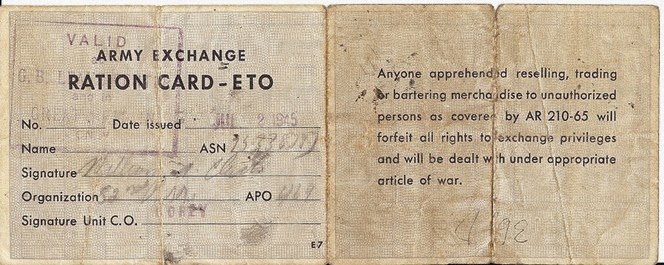

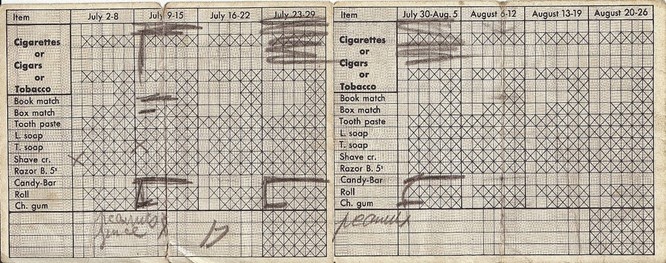

To have additional goods to sell, the men would visit the Army PX (Post Exchange) where they obtained their rations of cigarettes, cigars, tobacco, candy bars, peanuts, and chewing gum, etc. for trade.

Photos: 17 & 18: Bill’s Ration Card issued July 2, 1945 and used until August 5. Notice the warning about trade of goods to unauthorized persons. Source: Author’s Collection

A carton of cigarettes containing 10 packs which cost only 5o cents at the Army PX sold for 200 – 300 Marks on the black market. A single chocolate bar sold for 25 Marks. Source: Nordyke, P. “More than Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” 2008, p. 404.

Germans wanted any of the basic necessities of life, all of which were in extremely short supply. Unlike the Soviets they didn’t have much cash. Most of those lucky enough to work for the Americans earned cash, but they only received about 4.50 Marks per month in wages. Many German women turned to prostitution to earn money. Such women could be seen in the black market buying food and other basic goods.

Other desperate Germans would sell valuable cameras and items such as jewelry to Americans in exchange for a few cigarettes, or things like soap and coffee. An enterprising paratrooper could turn around and sell the jewelry and equipment to Soviets for their value in Marks. It was all pure cream. Some of it was used to fund the good times at the expensive Berlin nightclubs with more than enough left over to send home.

Those good times came to an end all too quickly as far as Bill was concerned. He had been on occupation duty in Berlin for approximately 60 days. As we will see in the next and final blog post, Bill was soon ordered to leave for home and his discharge from the Army.

© Copyright Jeffrey Clark 2014 All Rights Reserved.