For many years after the war Bill was silent about the Ardennes campaign. Perhaps the only person who really knew all of the details was his father, in whom he confided much about his wartime experiences. Although Henry Clark Sr. did tell Bill’s mother, Virgia, about his secret mission into Normandy three days before the drop, Henry took to the grave almost all else Bill told him. Whatever he told his father, Bill undoubtedly asked him to tell no one else.

Bill’s silence about the Ardennes campaign is typical of his humility and yet again it leaves frustrating unanswered questions concerning his involvement in it. Fortunately, there are enough bread crumbs to follow for this chapter of Bill’s war to piece together the puzzle of what happened to him and how he came to be in the Ardennes offensive. It is a story of deep loyalty, an indomitable will, and a supreme test of character against daunting odds which could well have cost his life.

It would not be until several decades after the war when Bill was in his seventies, that he talked openly about it. It happened at a family gathering at his aunt Eva’s home where his sister, Doris, two of his brothers, Henry and James (and his wife, Mary) had gathered for a visit. Henry Jr. , James and Mary had recently returned from a trip to Europe. One of the places they had visited was Verdun, France. Henry Clark Jr. had been stationed near there from September, 1944 to May, 1945 with the US Army Air Corps, 47th Liaison Squadron. Bill was stationed nearby with the 82nd Airborne in the vicinity of Reims, France. The close proximity allowed the brothers three precious visits to one another in March, April, and May of 1945. Eva and Henry were making jokes about something that Henry had done in the war, when Doris seized the opportunity and tactfully asked Bill if he was at the Battle of the Bulge.

Knowing Bill’s characteristic reticence to open up about the war, to everyone's quiet amazement Bill started talking. What he had to say took them by surprise. None of them had heard the story before because when asked about the war he would usually either ignore the questions, change the subject, or state that he didn’t want to discuss it. It was also more than a little scary to ask him pointed questions. Always the amiable jokester, if you did make the mistake of asking him an unsolicited war question, he would suddenly change character fixing you with a frightening stare from his cold blue eyes. They would mercilessly sear into you, leaving a permanent brand of uttermost embarrassment. Such was the intensity with which they conveyed his profound sorrow, regret and anger undiminished even 50 and more years on. With reactions like this, respecting his privacy on these matters became sacrosanct to the family.

In recounting Bill’s experiences during the Ardennes offensive, notes were used from interviews with his brothers, his sister, and his sister-in-law, together with materials from the “Military Biography of William A. Clark” by Herd L. Bennett, Attorney at Law, January 26, 2000.

Bill’s Ordeal in Reaching the 82nd Airborne’s Frontline Position via Paris - Reims - Liege - Werbomont

On Leave in Paris

Bill said that when the German offensive began he was on leave in Paris with another younger, green, inexperienced trooper whom he had taken under his wing. It was a day or so after they arrived in the city that he was approached by MPs while drinking in a bar. One MP physically handed Bill paper orders in an envelope and said they were entrusted to him. Not wanting to lose them, Bill said he stuffed the orders securely into his jacket pocket. The MP told him that his leave and that of his friend was cancelled effective immediately and that they were to return to base. Their was a rendezvous point where trucks would take them back. The younger trooper was not with Bill at the time.

Already a seasoned veteran of four campaigns, Bill sensed grave danger about this unexpected and apparently comprehensive cancellation of leave. There was a lot of confusion in the air and nobody could tell him what was really going on. Feeling responsible for his younger companion, and knowing they would be in deep trouble if they didn’t get back to base on time, he decided to go get him; then head together to the rendezvous area where the trucks would be waiting.

It took Bill some time to locate his buddy since he wasn’t where he thought he would be. When Bill finally tracked him down he was drunk with a woman in an obscure bordello. It was dark when they ran back to the rendezvous point, arriving just in time to see the trucks moving off. They ran toward them as they drove away, frantically waving their arms and shouting for them to stop, but no one in the convoy saw nor heard them. Their shouts and antics did draw the attention of the MPs at the rendezvous point. Fearful of being caught and thrown in jail for missing the convoy, the pair scampered off into the side streets and alleyways before they could be intercepted and detained. In telling this part of his story Bill’s voice quavered as the profound despair he felt that night unexpectedly came rushing back.

A large group of around 350 troopers from the 508 PIR were on leave in Paris at the same time as Bill and his buddy. Their experience mirrors Bill’s quite closely. Scheduled to return on Sunday night of December 17, they left their base in Sissonne, France on Friday morning, December 15 in a convoy of trucks bound for Paris arriving in the afternoon. Once they were assigned rooms the troopers avidly began indulging themselves in all that the famous “city of light” had to offer. Their trucks were parked in a large motor pool run by MPs. It was there that the troopers were to assemble on Sunday night for the ride back to base. Source: Nordyke, P., “Put us Down in Hell: The Combat History of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” 2012, pp. 391 – 392.

Unbeknownst to the 508 troopers in the afternoon of Saturday, December 16 the decision had been made to cancel leave and recall all men back to their stations around Reims. The order spread very quickly. MPs wasted no time and drove through the streets of Paris using loudspeakers calling the men to report back to their units. They scoured bars and whorehouses in an effort to leave no man behind. The troopers responded by assembling at the MP motor pool throughout the remainder of the afternoon. Four or five of the 508 men were unaccounted for when at 8:00 PM on Saturday, December 16 the trucks drove away reaching base early on Sunday morning. Source: Ibid.

Besides the few missing 508 PIR men, some troopers from the 505 and 504 did not make the truck convoy departure on December 16. In fact it has been recorded that as late as Sunday, December 17, MPs in Paris were still in the process of finding paratroopers who were unaware of the orders to return to base.

Colonel Tucker commander of the 504 PIR was holding a meeting with his senior officers and staff at 11:30 PM on December 17 detailing what was known about the German attack and organizing for the deployment scheduled for 9:00 AM on Monday, December 18. During the meeting one officer, platoon leader Moffatt Burriss, stated that some of his men were still on leave in Paris and that they would not know of the German attack. Colonel Tucker responded:

“As we speak, all military personnel in Paris are being rounded up. Your men should be back by daylight”. Source: Burriss, T., “Strike and Hold: A Memoir of the 82nd Airborne in World War II” 2000, pp. 165 - 167

The motor pool maintained by the MPs in Paris served the whole 82nd Airborne Division and likely other outfits. It was almost certainly the same place that Bill and his friend were running toward as the trucks drove away. But they were not running toward it on the night of December 16. As the timeline of subsequent events will reveal it was evening of December 17 that they missed the convoy Colonel Tucker referred to in his staff meeting held on the same evening. If they would have made it to the trucks on the night of December 17, they would have been back by daylight of December 18 in time to leave for the front.

Hiding themselves from the prowling MPs on the night of December 17, the pair carefully stole their way unobserved out of Paris in the pre-dawn hours of Monday, December 18. They hoped to hitch a ride back to Reims; a distance of about 145 kilometers or 90 miles. Based on inferences made in documented testimonies it was a drive that took somewhere between 6 – 10 hours in a troop carrier. That Monday was the first of several bitterly cold days and nights the two men would spend scrambling to reach their unit with only their summer uniforms to protect them against the worst Belgian winter in living memory.

The Journey Back to Base

After walking most of the day, they were able to flag down a civilian flat bed truck sometime on December 18. The language barrier proved to be very difficult, but Bill thought the driver communicated that on his way to his destination he would drop them off at Reims. The truck drove for several hours. There being no room in the cab, Bill and his buddy huddled together for warmth on the back of the exposed flatbed. When the truck pulled over to drop them off, they were still outside of Reims. They walked the rest of the way to their base where they found it deserted except for a contingent of guards. Bill said their duty was to guard the base while the 82nd Airborne was deployed.

Before the 504th PIR departed from camp Sissonne the decision was made to leave behind two men from each company as rear echelon. Furthermore kitchen personnel also stayed at the camp initially. Almost certainly, the same decision was made by the other 82nd regiments. Source: Campana, V., “The Operations of the 2nd Battalion 504th Parachute Infantry(82nd Airborne Div) in the German Counter-offensive, 18 December 1944 – 10 January 1945 (Ardennes Campaign) (Personal Experience of a Battalion S-3)” N.D., p. 6. Retrieved from Maneuver Center of Excellence Libraries, MCoE HQ Donovan Research Library, World War II Student Paper Collection. http://www.benning.army.mil/library/content/Virtual/Donovanpapers/wwii/index.htm

View Bill & his Buddy travel from Paris to their base near Reims in a larger map

Map 1: Bill and Friend's Approximate Route from Paris to the 505 PIR Base near Reims, France

The precise time they arrived at the base is not known, but Bill said guards stationed there told them that the Division had moved out earlier that day. The guards probably knew the general location where the 82nd Airborne had been deployed since it was expected that there would be cases of stragglers trying to get from the 82nd bases to their units at the front.

At first the 82nd had been ordered to Bastogne and the 101st Airborne had been ordered to Werbomont. However, while en route to Bastogne, General Gavin received an order from General Hodges, commander of the 1st US Army, to change the destination to Werbomont. The rationale was that Werbomont was the junction of key roads in the north of the Bulge which if captured would enable the Germans to move with ease in all directions and particularly toward their prime objective of Antwerp via Liege. Source: Ibid. p. 9.

It was logical to divert the 82nd from Bastogne since its men had departed before the 101st and at the time it was the closest of the two divisions to Werbomont. For the 101st, they were ordered to Bastogne. Source: LoFaro G., “The Sword of St. Michael: The 82nd Airborne Division in World War II” 2011, p. 439.

It is unknown to me whether the men guarding the bases knew of the precise location of the 82nd. It is reasonable to assume that they would have been informed via phone or messenger as soon as possible in order to alert stragglers to the change of deployment area.

The implications of this is that depending on when he arrived in Reims, Bill may or may not have known that he and his friend had to get to Werbomont. If they did know of the redirection to Werbomont, they probably weren’t given a good map of the route. On the night of December 17, working under intense time pressure, maps had been produced of the route to Bastogne by Division G-3 staff and these had been rushed to the Divisional units for use by the truck drivers. Source: Lebenson L., “Surrounded by Heroes: Six Campaigns with Division Headquarters, 82nd Airborne Division, 1942 – 1945. 2007, p. 166.

Perhaps there was a wall or desk map left behind showing the route the Division took to get to Bastogne. It may or may not have indicated the route the 82nd used to drive to Werbomont. If there was such a map, late comers could have used it to draw their own rudimentary “mud maps” of the route. There would not have been sufficient copies made for use by individual or small groups of non-ranking stragglers.

For Bill and his friend there were no vehicles left that they could take. All forms of transportation either had been taken by the Division units when they initially departed for the front on the morning of December 18, or were taken by stragglers before Bill and his friend arrived at camp, or were reserved for other uses.

One such straggler was the 18th Airborne Corps commander General Ridgway himself, as well as his staff.

“At 0830 [8:30 AM], Ridgway and the corps personnel (and strays from the 82nd and 101st) took off [from England] in fifty-five IX Troop Carrier planes. In spite of the terrible weather, all planes landed safely in Rheims between 1100 and 1300 [11:00 AM and 1:00 PM]”. Source: Blair C., “Ridgway’s Paratroopers: The American Airborne in World War II” 1956, p. 365.

After arriving at the airfield near Reims, Ridgway and his staff then drove to nearby Epernay about 20 miles south, where the advanced 18th Airborne Corps CP was located. The 82nd Airborne had already departed and Ridgway stayed in Epernay until the last battalion of the 101st was on its way to Bastogne. His staff procured some old sedans (the only transportation available) and set out to Werbomont via Bastogne with thick fog and drizzle obscuring everything. The roads were jammed with heavy traffic going both ways. They arrived in Bastogne and stayed the night. The next morning December 19, Ridgway discovered rumors had spread that the city was surrounded. He wasn’t worried, however. His paratroopers were used to being surrounded. It was how they fought. He departed at first light en route to Werbomont where he was to establish the 18th Airborne Corps CP. The route took him north through Houffalize and Manhay a distance of 40 miles. A sixth sense warned him that the Germans might have taken Houffalize, so he diverted around the town, safely reaching Manhay and then Werbomont. That same morning the German spearhead had taken Houffalize. Source: Blair C., “Ridgway’s Paratroopers: The American Airborne in World War II” 1956, pp. 365-366.

The Long Cold Slog from Reims, France to Liege, Belgium

A point worth noting is that Bill was definitely working under the belief that he had to reach his unit in the 82nd Airborne at the front. If his orders mentioned only that he had to return to base, then he could have stayed there with his friend perhaps helping as rear guards. Their orders must have included information specifying that they reach their unit. Their unit must have been sent to the front with the rest of the 82nd. To obey the orders they decided to make it on their own.

The next thing Bill said they did was walk in the direction of Liege, Belgium via their base near Reims. Liege, itself is some 160 miles north of Reims and around 250 miles north of Paris depending on the route taken.

Knowledge of the precise route they took is lost. However, following the route taken by the 82nd to Werbomont could have put them too close to the front to find a ride, or worse taken them behind German lines. At that time it was known that the German offensive was headed west, but no one really knew its strength, how fast it was moving, nor the breadth of the offensive. For all they knew, the northern parts of the roads used by the 82nd may well have been overrun already, which was indeed the case as reported in General Ridgway’s experience on the morning of December 19.

Indeed some of the northern route was unsafe even before general Ridgway made the journey on December 19, and specifically by the time the last of the 505 PIR convoy had passed through on December 18.

“We [the 456th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion(PFAB)] were three hours behind the head of the of the 505th RCT’s column, bringing up its rear. Battery C, the last unit in a trailing serial, was fired on by German guns at the Houffalize intersection. They were not stopped and suffered no casualties. It was only through the greatest of good luck that the entire 82nd Airborne Division passed the intersection without any serious interference”. Source: McKenzie J., “On Time On Target: The World War II Memoir of a Paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne” 2000, p. 95.

Map 2: Routes taken by the 82nd Airborne from the Reims Area to Werbomont Belgium (published after the fact) Source: 82nd Airborne After Action Report, 29 March 1945

It is unknown how much of the situation Bill knew or suspected. It is known that he decided on travelling to Liege. So Bill’s most probable rationale (considering the possible extent of the German advance) was that the road north out of the large town of Reims gave them a better chance of catching a ride to Liege due to a larger likely comparative volume of traffic. Vehicles heading from Reims to Liege would probably take the more western route to give the advancing Germans a wide birth. If Bill and his friend could get to the city of Liege they would have been in a good position for finding the location of the 82nd and of catching a ride to it.

View Bill's Journey to the Battle of the Bulge in a larger map

Map 3: Bill’s Probable and Approximate Route from the 505 Base near Reims to the 82nd Airborne’s Position at the Front

But traffic heading to Liege proved sparse. Almost all of it was heading in the opposite direction away from the battle zone. The pair slogged their way along roads of snow and ice. Nights were spent in whatever shelter could be found including frozen roadside ditches. With each passing frigid day and sleepless night of plummeting temperatures, they suffered increasingly from exposure and exhaustion. After several days enduring these conditions still only clothed in their summer uniforms, the haggard men almost did not register it when a civilian truck stopped and offered them a ride. Before their minds could decide what to do, their dumb bodies clambered into its cab. They shivered uncontrollably for hours. Bill said he gathered the truck was bound for some place near Liege. At that stage he did not care where it was headed. The warmth it provided was all consuming.

A long trip later the truck dropped them off in an unknown village somewhere in the vicinity of Liege. Exhausted from their harrowing journey the pair laid up in the village to rest. Two days later after regaining scant strength they recommenced their journey. Bill could not tell where the village was in relation to the 82nd’s position. He made several inquires, but no one knew anything. At night he saw flashes in the sky to the east which gave him a bearing on the general direction of the front. So he decided they would start walking that way. Perhaps he used his rudimentary map if he indeed had one. Once they arrived at the front, or along they way, he hoped they would find an Allied unit of some kind which would point them to, or better yet, take them to the 82nd Airborne. So he and his buddy started walking eastward in the lethal winter conditions.

At some point they flagged down a tank retriever. As luck would have it, the driver told them he was headed to the 82nd’s position at the front. The distance from Liege to Werbomont is about 25 miles. They climbed onto the hull of the vehicle somehow finding the strength to endure the icy wind chill as their slow moving ride lurched toward its destination.

Photo 1: A Grant ARV (Armored Recovery Vehicle) AKA Tank Retriever used in 1945 to retrieve damaged vehicles from battle fields Source: Wikipedia Commons

Arrival Worse for Wear at the 82nd Airborne Division’s Position in the Vicinity of Werbomont, Belgium

Bill said it was a very cold day when they finally arrived. He and his buddy were in awful shape. They were still suffering from exposure and their condition was worsening. Even after the rest in the Belgian village, the march to the front and ride on the exterior of the tank retriever had taken their toll. Moreover, Bill said they had eaten very little to no food for a week.

The tank retriever dropped them off somewhere in the 82nd Airborne’s zone of operation. Soon after an officer in a jeep from the 2nd Battalion 505 PIR was driving by and recognizing Bill, pulled over to talk to him. He listened to the pair’s story while assessing their physical condition. Referring to their generally poor appearance, the officer said he didn’t think they could do much good. Speaking for himself, Bill wryly replied, “I may look bad, but I can still pull a trigger.” Source: Herd L. Bennett, Attorney at Law,“Military Biography of William A. Clark” January 26, 2000 p. 20.

Taken to a Medical Station for Assessment and Aid, but Which One?

The officer told them to get in the jeep and drove them to a medical station where triage was being performed on wounded personnel. Bill described the building housing the casualties as a “cow barn”. He said it was horrific place filled to overflowing with sick, wounded, dying and dead men. He said there was a lot of blood everywhere and:

“…it looked as if everybody in the 82nd was shot up – decimated”. Source: Herd L. Bennett, Attorney at Law,“Military Biography of William A. Clark” January 26, 2000 p. 20.

There were two medical units serving the 82nd Airborne in the Battle of the Bulge. One was the organic 307th Airborne Medical Company composed of 15 Officers and 187 Enlisted Men. The other was Detachment A of the 50th Field Hospital composed of ten officers, six Nurses and 47 Enlisted Men. It was attached to the 82nd Airborne Division before the Ardennes offensive and served as part of the 307th during the battle. Immediately upon arrival the 307th set up a Clearing Station composed of tents one mile east of Werbomont. Source: Author Unknown, 307th Airborne Medical Company: Unit History. Retrieved from http://www.med-dept.com/unit_histories/307_abn_med_co.php

Then on December 26 the Clearing Station was moved to Chevron. There, in a hotel, medical services were provided. The distance from the front to the rear meant that an advanced Collecting Station had to be set up. Source: Ibid.

The location of this advanced Collecting Station is not mentioned in the 307th Unit History and the date it was setup is not clear.

On January 3, the 307th Airborne Medical Company moved the advanced Collecting Station to a “comfortable building” in Haute-Bodeux, which proved adequate size for treating casualties, but was too small to accommodate the Enlisted Men, most of whom had to stay in tents around the facility. Source: Ibid.

I have since found a description of the advanced Collecting Station that closely matches the one Bill gave of the medical station he and his friend were taken to by the 2nd battalion 505 officer. In his memoirs, Spencer Wurst, a 505 trooper from the 2nd Battalion, Company F wrote:

“I had been feeling terrible for three or four days just before Christmas week, as though I had recurrent malaria. Lieutenant Hamula sent me to the [2nd] battalion aid station, where the surgeon diagnosed me as a bad case of bronchitis going into pneumonia. I was confined to a litter and evacuated to a collecting station by a quarter-ton ambulance, a jeep that had litter racks mounted on the sides and back.

It was after dark on Christmas Eve when I arrived at the collecting station, a large, barn-like building housing up to seventy-five litter patients. The whole place looked like a scene from hell. The medical personnel were past the point of exhaustion, working by lanterns amidst terrible moaning and groaning. As we were brought in, the staff checked our emergency medical tags and gave us a quick examination, grouping arriving casualties by the severity of their wounds or illnesses, according to the practice of triage. Those with little or no hope of surviving were low priority, while those who had severe wounds but could be saved by immediate operation were moved to the top of the list.

Horrific pictures of this collecting station remain in my mind to this day. There was little or no heat. People were dying all around me. There were some very badly wounded, and many burn cases from armored outfits where the tanks had caught fire. All of them had bloody clothes. I felt guilty as I lay there, because so many were much worse off than I was. There were also many cases of trench foot, who were maybe as ‘well off’.” Source: Wurst S., & Wurst G. “Descending from the Clouds: A Memoir of Combat in the 505 Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division” 2004, p. 230.

Bill’s description of the medical station being in “a cow barn”; his memory of the condition of the patients being sick, wounded, dying and dead; and of the place; there was blood everywhere, and “it looked as if everybody in the 82nd was shot up – decimated” is very similar to that of Spencer Wurst’s “…barn-like building…” with “…People…dying all around me…” and “All of them had bloody clothes…”

The Unit History of the 307th Airborne Medical Company states that there were only four locations serving the 82nd Airborne’s medical needs outside of the individual Battalion Aid Stations. These were: the tent Clearing Station one mile east of Werbomont functioning from December 19 – 26; the Clearing Station run in the hotel in Chevron east of Werbomont functioning from December 26 onwards; an advanced Collecting Station closer to the front in an unknown location established at an unknown time which was then moved on January 3 to Haute-Bodeux. Source: Author Unknown, 307th Airborne Medical Company: Unit History. Retrieved from http://www.med-dept.com/unit_histories/307_abn_med_co.php

These medical installations minus the first and unknown position of the advanced Collecting Station are plotted in Map 4 below.

The 2nd Battalion 505 officer who gave Bill and his friend the jeep ride would have taken the men to one of the 307th Airborne Medical Company’s facilities since they were the only medical stations in the area. Given the similarity of Bill’s description of the medical station and that of Spencer Wurst’s Collecting Station, (both as a barn), the only likely station is the advanced Collecting Station of unknown location mentioned in the History of the 307th Airborne Medical Company. It could not have been either of the Clearing Stations near Werbomont, nor Chevron, since they are respectively described as being composed of tents, and a hotel. It could not have been at the “comfortable building” near Haute-Bodeux because that Collecting Station was established on January 3 and Spencer Wurst said he arrived at the barn like Collecting Station on the evening of December 24.

View 307th Airborne Medical Company Stations in a larger map

Map 4: Approximate Locations of the Medical Stations of the 307th Airborne Medical Company in the Battle of the Bulge

Note: Two Clearing Stations and location of the second advanced Collecting Station are displayed. The location of the initial advanced Collecting Station is unknown.

Determining the Date of Bill’s Arrival at the Front

The 307th Airborne Medical Company’s initial advanced Collecting Station in the unknown location must have been in a barn behind the defensive line occupied by the 82nd units on December 24 for Spencer Wurst to have been admitted to it on that night. He said he arrived at the Collecting Station “…after dark on Christmas Eve…”.

Bill and his friend’s arrival at the 82nd must have been several days after December 19 - 20, the dates the 82nd units had first been deployed. Given Bill’s description of the medical facility, their date of arrival must have been at a time when a lot of sick and wounded soldiers were filtering back through the lines.

Bill mentioned that when they arrived he had eaten little or no food for a week. Earlier it was determined that he and his friend started walking from Paris towards Reims on the morning of December 18 and caught a ride later that day before walking again to reach their base. They probably would have arrived at base the afternoon or evening of December 18. After their long journey from Paris, they probably would have eaten at the base before heading to Reims.

So the last definite opportunity to eat something substantial would have been late on December 18 or the morning of December 19 depending on when they departed for Reims. A week after those dates is either December 24 or 25 and would place them with the 82nd at the front sometime on either of those dates.

As an aside, while it is theoretically possible that they took food with them before they left the base, it is unlikely to have been anything worth mentioning. The 82nd had taken what meager rations were available with it to the front. These rations consisted of very little. Spencer Wurst wrote about the distribution of food on the morning of December 18 to 505 PIR troopers:

“One day’s worth of K and D rations was all we had. We literally went into the Ardennes with nothing much to eat but candy bars.” Source: Wurst S., & Wurst G. “Descending from the Clouds: A Memoir of Combat in the 505 Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division” 2004, p.215 - 216.

Others were a tiny bit more fortunate. James Megallas of the 504 PIR wrote of the hasty preparations for departure his company was making early in the morning of December 18:

“The company area was a beehive of activity. Two days of K rations and two D rations (hard chocolate) sent down from division were distributed.” Source: Megellas, J. “All the Way to Berlin: A Paratrooper at War in Europe” 2003, p. 182.

Bill and his friend must have arrived at the front in time to see the stream of the casualties arriving at the Collecting Station from the retreat on the night of December 24. These wounded were not only 82nd men. They were the men from the armored units and infantry who retreated through the 82nd Airborne's line on the night of December 24/25 after fighting in the St. Vith pocket. It is unknown when the last of these men were processed through the 307th Collecting Station, and the Clearing Station. Movement through the winter conditions was slow, but the retreat was completed by December 25. Given Bill’s description, it is reasonable to conclude that he and his friend arrived in time to see it. Probably on December 25. Bill’s description fits with that timeframe and with what Spencer Wurst saw on the night of December 24.

What this means is they they arrived at a time when the forward Collecting Station was located in a barn and when the 2nd, 9th, and remnants of the 1st SS Panzer Divisions were perusing the 82nd and US Army outfits (retreating from the St. Vith pocket) back to their new lines of defense on December 24 - 25.

The 307th Airborne Medical Company Unit History unfortunately does not provide complete figures for the casualties during the battle for December, 1944. It states that for December there were 95 cases of exhaustion from combat and 115 trench foot injuries. Source: Author Unknown, 307th Airborne Medical Company: Unit History. Retrieved from http://www.med-dept.com/unit_histories/307_abn_med_co.php

The 82nd Airborne Division after action report for the Battle of the Bulge states that inclusive of December 31, 1944 the battle and non battle casualties for organic and attached units was 1618 enlisted men and 76 officers. These numbers are more than enough to account for what Bill and Spencer Wurst witnessed especially when it is known that many wounded personnel received medical treatment during the retreat on December 24 – 25.

Medical Treatment, Interrogation, and Unit Assignment

Sometime after arriving, Bill and his friend were interrogated to validate their story. Bill produced the paper orders he had stashed in his jacket, and told of their ordeal. They were both cleared of any potential wrong doing for being AWOL. He said that he subsequently volunteered for combat duty and was assigned to a unit. He did not explain to which unit, what happened to his buddy, nor anything about the remainder of his time in the 82nd Airborne’s sector in the Bulge. He only said that after it was over:

“Headquarters took the 82nd out of the front lines. They always took us out first – I guess because they wanted to save us for another slaughter someplace else.” Source: Herd L. Bennett, Attorney at Law,“Military Biography of William A. Clark” January 26, 2000 p. 21.

He also remembered arriving back at his base near Reims in February, 1945.

Because of their condition upon arrival he and his friend must have received treatment for exposure, were given food, and scrounged around for some warmer clothes.

The unit Bill was assigned to before the Ardennes offensive was launched by the Germans almost certainly was Service Company 505 because at this point in the war that was his parent company when not assigned to temporary duty with the 82nd Parachute Maintenance Company (PMC) Provisional. The exception to this being those cases where he was assigned to combat companies and other units during combat jumps.

He obviously was compelled to reach the 82nd Airborne’s front line position to rejoin his unit at the front. Service Company was unquestionably at the front as was documented in the last blog post, when on December 22, 40 Service Company troopers from the 505 PIR took their rifles and plugged a hole in the line through which Panzer Grenadiers of the 9th SS Panzer Division had attempted a penetration. The Service Company troopers successfully through them back, halting the attack and closing the breach. The photo below, also provides evidence that Service Company 505 continued to participate by providing for the needs of combat companies deployed on the front lines.

Photo 2: Vehicles of and Troopers of Service Company 505th PIR in the ‘Battle of the Bulge’, January 1945 Source: National Archives

However, given the fact that Bill had combat experience he may have been temporarily assigned to a combat company. The ranks of the 82nd were thinned by the fighting and cold and they would soon have to counterattack on January 3, 1945, advancing over a wide front. Every able bodied man with combat experience was precious and most riggers including Bill were seasoned combat veterans.

As was mentioned in the last post on the Battle of the Bulge, when the 82nd Airborne was relieved by the 75th Infantry Division, the men were sent to towns in Belgium over the period of January 12 - 20 to rest and recover. Some were even able to make trips to France.

“Once we [2nd Battalion 505] had settled in around Chevron, we were told we would rest there for at least two weeks as long as no unusual emergencies arose. During this period commanders were able to provide everyone not under arrest with a three-day pass. The lucky ones went to Paris and Brussels, and a few went to Liege or Spa.” Source: McKenzie J., “On Time On Target: The World War II Memoir of a Paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne” 2000, p. 124.

During this time, Bill wrote a letter to his sister, dated January 14, 1945. It is a brief letter. He does not talk about his ordeal in reaching his unit. Bill rarely wrote letters home so the purpose of this letter was to convey a simple message that he was okay. Back in the US, the family were aware of the Ardennes offensive and the 82nd Division’s role in it. The letter was his way of informing them that he was still alive. The return address is also important because it states his unit assignment (at least on January 14, 1945) as Service Company:

Pvt. W. A. Clark 15378297

Det. 1/ Ser. Co. 505 Prcht. Inf.

apo. 467 c/o Post Master. Ny. Ny.

The date of the letter is coincides with the dates that the 82nd was recovering in Belgian and French towns. In one of those towns he rested and recovered before the 82nd was called upon again to eliminate the Bulge by fighting the Germans back to the banks of the Rohr river from January 28 - 31. He then proceeded with the 82nd and fought in the Hurtgen Forest from February 7 - 16, before the Division returned to camps in the Reims area on February 19, 1945. Source: “Four Stars of Valor: The Combat history of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2006 pp. 378 - 388.

As was his habit, Bill kept souvenirs of various types from the places where he had fought. Bill carried two bibles with him throughout the war. One of larger format dating back to his basic training at Camp Wheeler, Georgia and another of smaller format dated March 17, 1943 from his time in paratrooper training in Fort Benning, Georgia. This Belgian 10 Franc note was found in the larger bible where he had also stashed money from France, and Germany.

Photo 3: A 10 Franc note from the National Bank of Belgium. This side of the note is in French. Source: Author’s Collection

Photo 4: This Opposite side is in Flemish Source: Author’s Collection

The 82nd PMC Riggers on Assignment in England

At the time Bill was in the Ardennes, his temporary duty unit, the 82nd PMC (Parachute Maintenance Company) Provisional was in England. They didn’t arrive anywhere near the Ardennes until February 19, 1945 when they reached their new base in France near Sissonne – popularly known as Camp Moaning Meadows.

Here follows a chronology of the actions carried out by the 82nd PMC (Provisional) from October 7, 1944 through to February 19, 1945:

| “At about the end of the three weeks, [three weeks after the 17 September jump is October 7] the parachute maintenance men left Nijmegen by truck travelling to Brussels, then by plane on to England with the chutes the 504 combat team had salvaged… At this time, boxing up of another move was the order of the day. On Christmas day of all days, a move came up although it wasn’t the expected move. Thirty men moved out on short notice by truck with only a few accessories and found out what the word “cold” meant on that ride to southern England. The remainder of the riggers followed within a few days with the men splitting up into more small sections to work at airfields around Reading. They set up tables and started packing a rush order for equipment chutes for the 1st Allied Airborne Army, and the 490th Airborne Quartermaster Battalion, to resupply outfits that were encircled in the “Bulge”. This rush order consisted of packing 50,000 equipment chutes,; 43,194 of those being packed in 11 days. This number figures to read 35 per man a day, but since all men logically cannot pack at once this figure reveals that from 70 to 100 chutes were packed per table each day. Returning to Ashwell Camp, a little before the middle of January, the men immediately began transferring the hundreds of boxes of equipment from Cottesmore to Oakham by truck, loading it into box cars. Working in the dampness and cold, they loaded 432 English box cars of equipment in five days. The detachments next left Aswell Camp behind. The men pulled away from Oakham by train, going to Camp Hursley near Southampton, England. For two weeks they did nothing but suffer from the continuous diet of C rations, and try not to sink in the mud above their ankles. Finally the men sailed across the Channel, then layed over for a few days in Camp Twenty Grand, near Le Harve. Moving out, they traveled for a couple of days on “40 and 8’s”, during which one 508 man was severely injured about the head, finally reaching their destination on the 19th of February 1945. The new camp was four miles south east of Sissone, France, more popularly known as ‘Camp Moaning Meadows’.” Source: Author Unknown, “82nd Airborne Division: 82nd Parachute Maintenance Company” Section 1 Unit History, Date unknown, p. 12. |

Despite these facts on the whereabouts of the 82nd Airborne PMC (Provisional), Bill’s service record (analyzed in the Appendix below), and story of his involvement in the events of the Battle of the Bulge are clear evidence that he was not assigned to his rigger unit in England at the time the 82nd Airborne was fighting in the Ardennes campaign.

What was Bill’s Assignment and Why was it on the Continent Instead of in England?

Why was Bill stationed in Reims when the 82nd PMC (Provisional) was stationed at Ashwell camp in England?

The answer lies in what happened after Operation Market – Garden. The 82nd Airborne’s role in the Rhineland campaign was finished when Canadians relieved the Division on November 10, 1944. Source: “Four Stars of Valor: The Combat history of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2006 p 315.

On November 16 they moved by truck to their new base in camps around Sissonne and Suippes, near Reims, France. Source: Langdon, A. “Ready: The History of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment , 82nd airborne Division, World War II”, 1986 p. 121.

As soon as the troops arrived General Gavin, not believing that the Germans were finished, began training in earnest. New men were coming into the Division at that time and they needed to be trained. He established a rudimentary jump school to increase the standards of the 82nd’s “airworthiness”, as he put it. Most of the old men who had been in battle in Holland were given furloughs to Paris and England. Source: Booth, T., (1994) “Paratrooper: The life Gen. James M. Gavin” p 243.

As will be explained in a subsequent blog post, two airstrips in the Reims area had been established by the 508th PIR prior to the arrival of the 505 and 504 PIRs. The 508 PIR had also set up a rigging facility south of Sissonne.

The explanation for how he arrived in Reims before the main force of 82nd PMC (Provisional) personnel is that Bill indeed did head back to England with the men from the 82nd PMC (Provisional) on October 7 as per the History of the 82nd PMC. Like most of the 82nd men who had fought in Holland he was given a six day furlough after the fighting was over. He spent his furlough in England in November of 1944 as he stated in the letter he wrote home to his sister dated January 14, 1945. The letter reads:

“I had a six day furlough in England last November. Had a very good time, but I spent a lot of money… A person can have a good time in London but it costs a lot for food etc.” Source: William Clark “Letter to his sister Doris Clark”, January 14, 1945 p. 1

Soon afterward he, and possibly other 505 riggers, were assigned to duty at Reims to pack parachutes, retrieve and repair used parachutes as part of the rudimentary jump school activities that General Gavin had put in place to train the new men arriving into the Division.

It would not have been the first time he was sent ahead or separately from the rest of the 82nd PMC men. He had done so in Northern Africa (as was posted here) where he was involved in shipping a kitchen via C-47 which crashed in the Atlas Mountains and in Northern Ireland (as was posted here) after the Italian campaign was over for the 505 PIR.

These 505 PIR riggers assigned to duty in Reims were probably based at Camp Moaning Meadows near the town of Avaux, France. They were likely assigned to the 505 Service Company.

Sometime after he arrived in Reims, Bill landed a pass to Paris just before the German offensive was launched. The passes to Paris ranged from 2 to 3 days in length and had begun at the end of November right up to the beginning of the Ardennes campaign. Source: Lebenson L., “Surrounded by Heroes: Six Campaigns with Division Headquarters, 82nd Airborne Division, 1942 – 1945. 2007, p. 165.

Bill’s pass must have been issued for the weekend of December 16 – 17, 1944. It is interesting to contemplate how different his experience and possibly his chances of survival might have been if he had not been in Paris that weekend. They may well have been improved.

One has to respect the unassailable determination, stout endurance, and loyalty of Bill and his friend in marching most of the 250 miles to the front in that terrible cold. It had nearly killed them. Yet they kept going, never even considering turning back.

It is a testament to the intense regular training General Gavin had designed and led his paratroopers on – not least of which consisted of the 90 plus mile marches in full pack at night. That and growing up in the privations of the Great Depression had made them into hardened supermen by today’s standards. For his part, Bill was no stranger to cold. Until his enlistment, he had lived on the family farm in Ohio where the winters are cold. The day of his funeral, for instance, my phone displayed that the local temperature had fallen to 8 degrees Fahrenheit (a little more than -13 degrees Celsius).

Appendix

Bill’s Service Record and the Ardennes Campaign

Bill’s Bronze Service Star for the Ardennes Campaign

Bill’s recollections of the Ardennes campaign are reflected in his service record. His Honorable Discharge states under 33. Battles and Campaigns that he received a Bronze Service Star for the Ardennes Campaign and the Belgian fourragère.

A noted in previous posts, photographic evidence was presented in the post Normandy Part 1: Establishing Bill’s Presence in the Invasion which demonstrated that his Honorable Discharge accurately reflects the number of campaigns in which he said he had participated. Photo 1 of that post shows pinned to his breast an Arrowhead Device as well as one Silver Service Star, in lieu of five Bronze Stars, and one Bronze Service Star. The six campaigns were Sicily; Naples-Foggia; Normandy; Rhineland; Ardennes; and Central Europe. In the first post on Normandy, it was mentioned these are not Bronze Star Medals, which were awarded for valor in combat. They are Bronze Service Stars (sometimes referred to as Bronze Battle Stars). Each one indicates that Bill was physically present in the zone of combat during the time frames of the respective campaigns.

Eligibility for the Ardennes Campaign Bronze Service Star

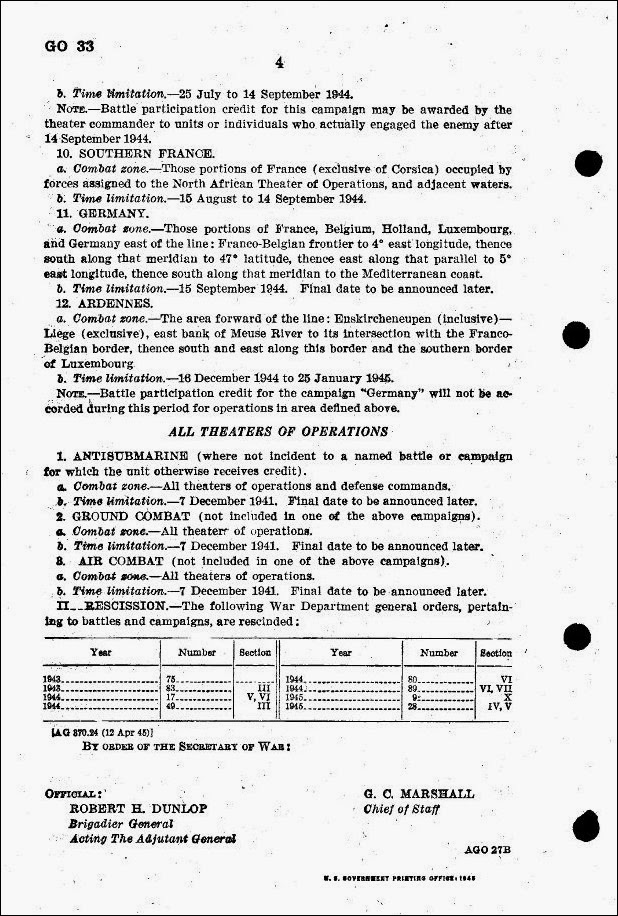

In the case of the Ardennes, the facts about Bill’s Bronze Service Star can be verified by General Orders 33 War Department 1945 (AKA GO 33 WD45) partly reproduced below:

Top Section Identifying General Order 33 War Department 1945 (AKA GO 33 WD45).

Source: “Maneuver Center of Excellence Libraries Donovan Research Library US Armor Research Library Historical General Orders/Special Orders Collection: General Orders 1945 copy 2” Retrieved from http://www.benning.army.mil/library/content/Virtual/General%20Orders/GeneralOrders/DAGO1945.pdf

Page 4 of General Order 33 War Department 1945 (AKA GO 33 WD45)

Source: “Maneuver Center of Excellence Libraries Donovan Research Library US Armor Research Library Historical General Orders/Special Orders Collection: General Orders 1945 copy 2” Retrieved from http://www.benning.army.mil/library/content/Virtual/General%20Orders/GeneralOrders/DAGO1945.pdf

Page 4 of GO 33 WD 45 states the conditions for receiving a Bronze Service Star for the Ardennes campaign:

| 12. ARDENNES. b. Time Limitation. – 16 December to 25 January 1945 |

To be eligible for the Bronze Service Star for the ARDENNES Campaign , a soldier had to be present for duty (during the period from 16 December to 25 January 1945) in the combat zone of the areas forward of the “Euskirchen – Eupen” line not including the city of Liege and east of the Meuse river bank from the French-Belgian border southeast to the southern border of Luxembourg. See Map 5 below for the dimensions of the combat zone.

View Ardennes Combat Zone in a larger map

Map 5: Combat Zone for the Ardennes Campaign

As stated Army Regulation 600–8–22, Paragraph 5-13 c. (concerning Award of Bronze Service Stars to the EAME Campaign Medal in WWII) a Bronze Service Star is authorized when a soldier was assigned to a unit and present for duty with that unit at the time the unit participated in combat; he was under orders in the combat zone; and he was either awarded a combat decoration; or had a certificate from a commanding general that he participated in combat; or he served at a normal post of duty.

Basically, a soldier had to be assigned to a unit which was present in the location of the combat zone when the battle was still occurring to be eligible for the award. Presence in that location after it was liberated and the battle was over would make the soldier ineligible for the Bronze Service Star.

The combat zone in paragraph 12 a of GO 33 WD 45 above included the places east of the Salm River where the men of the 82nd Airborne fought. The Bronze Service Star for Ardennes is proof that Bill was physically present and participated in the 82nd Airborne’s battles in the vicinity of points west of the Salm River which included among others: Werbomont, Basse-Bodeux, Trois Ponts, Fosse, Reharmont, Grand-Halleux, Arbrefontaine, Goronne, and Vielsalm . These place names can be found in Maps 3 and 4 above and in the previous post on the 82nd Airborne in the Battle of the Bulge.

Bill’s Belgian Fourragere

Bill’s honorable discharge record also shows that he received the Belgian fourragere. The citation for it states:

| “At the proposal of the Minister of National Defense, we have decreed and we order: Article 1: The 82d Airborne Division with the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment attached is cited twice in the Order of the Day for the Belgian Army and is herewith given the fourragere of 1940, for:

Article 2: The Minister of National Defense is herewith ordered to execute the decree. For the Regent: THE MINISTER OF NATIONAL DEFENSE signed L. MUNDELEER.” |

The Belgian fourragere is a unit award as specified in the post on Foreign Decorations. There is a cord device worn by individual 82nd Airborne members. The award applies to all units of the 82nd Airborne Division. To wear it permanently 82nd Airborne soldiers needed to at least be assigned to a unit in the 82nd airborne Division during the period of from December 17 to December 31, 1944 (see dates in citation 1 above) and from January 1 to 23, 1945 (see the 23 day time frame in citation 2 above). They did not have to be present in the combat zone to be eligible for permanent wear. The 82nd Parachute Maintenance Company (PMC) Provisional was not in Belgium at the time of the Ardennes Campaign. Most of its men were in England at Ashwell camp. Yet they were assigned to the Division and so are authorized to wear it permanently. They are listed as receiving the Belgium fourragere on page 141 of DA Pam 672-1 . Unit Citation and Campaign Participation Credit Register.

Unlike the Dutch Orange lanyard, which states that only members of the 82nd Airborne who fought in the battles around Nijmegen Holland are allowed to wear the award, the Belgium citation is not clear on this.

In any case, as per his Bronze Service Star, Bill was present for duty in the Ardennes combat zone during the period 16 December to 25 January 1945 as stipulated in GO 33 WD 45. Since Bill met the criteria for the Bronze Service Star of the Ardennes campaign, the appearance of the award on his honorable discharge provides evidence that he did participate in the actions recounted in the Belgian decree reproduced above.

© Copyright Jeffrey Clark 2013 All Rights Reserved.

![Bundesarchiv_Bild_183R65485_Joachim_[2] Bundesarchiv_Bild_183R65485_Joachim_[2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEii_A4_Qn-XctqasfhSER-2PLu_MCmbs4_HqgsV9E9hT8VbPUKvTSMKXnyd-6Jxb3Lv75QvAGPsT9IZXyP_DbH5QZRVNnF8IIeoUNPn8pUXoc-odDTt7mrFZkPnztUOzW87Hm1KO1GveYI/?imgmax=800)