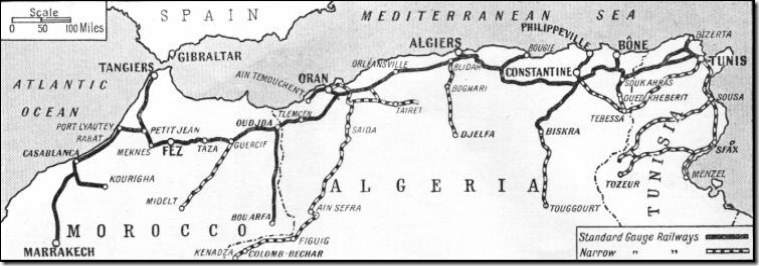

82nd Airborne Training Base Near Oujda, French Morocco, North Africa May – July 1943

Bill often made comment that the time at Oujda was the worst he experienced during the entire war. Matthew Ridgway, Commanding General of the 82nd Airborne handpicked the area near Oujda in French Morocco as the Division’s training base. He believed the conditions there would harden the troopers for the extreme trials of combat they would soon face.

“We had picked, on purpose, land that was not in use for grazing or agricultural purposes. We trained in a fiery furnace, where the hot wind carried a fine dust that clogged the nostrils, burned the eyes, and cut into the throat like an abrasive. We trained at first by day, until the men became lean and gaunt from their hard work in the sun. Then we trained at night, when it was cooler, but the troopers found it impossible to sleep in the savage heat of the African day. The wind and the terrain were our worst enemies. Even on the rare calm days, jumping was a hazard, for the ground was hard, and covered with loose boulders, from the size of a man’s fist to the size of his head.”

Source: Matthew Ridgway and Harold Martin, “Soldier: The Memoirs of Mathew B. Ridgway” 1965, p. 65

Oujda was located about 30 miles (~ 48km) from the coast. The 505 set up camp a few miles outside of town on some open ground adjacent to a large French airfield which was to play a central part in their jump training.

“A C-47 with glider in tow training at Oujda, French Morocco, North Africa, on 17 June 1943.”

(Gives an idea of the terrain around the Oujda training base)

Source: Photo Courtesy of U.S. Army

It was unbearably hot. Temperatures in the shade of 115 - 120 degrees Fahrenheit (~ 46 – 49 degrees Celsius) regularly baked the place. Cases of heat exhaustion quickly mounted, but it wasn’t only the heat that made Oujda the hell it was. It was the flies and the sand and the diseases they carried.

“Making life even more miserable for the men were the African flies that attacked them ‘as one dark and horrible force’ without mercy, determined to destroy them ‘body and soul’.” Source: Barbara Gavin – Fauntleroy “The General & His Daughter” 2007, p. 15

A prevailing wind brought in the flies and sand contaminated with animal dung. These got into everything. Cases of Typhus and Malaria sprang up and were soon followed by waves of dysentery which quickly spread through the camp, making no distinctions across rank.

“…an entrenching tool became a standard part of everyone’s daily uniform. This malady was so universal and struck so suddenly it became commonplace to see someone break ranks and tear off to some unoccupied part of the desert, with no explanation needed or demanded. Toilet paper became more valuable than French franc notes.” Source: Allen Langdon “Ready: A World War II History of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment” 1986, p. 12

Colonel James M. Gavin commander of the 505th (later General of the 82nd Airborne) wrote home about the dysentery in a letter to his daughter.

“Soldiers call everything associated with the Army ‘G.I.’ To their delight, the medicos referred to this ailment as the ‘GIs’ meaning gastro-intestinal disorder.” Source: Barbara Gavin – Fauntleroy “The General & His Daughter”2007, p. 24

The 505 veterans denounced the food at Oujda as terrible, but with everyone suffering from the ‘GIs’ at one time or another, it was perhaps their least concern. Everything they were fed was the same canned or powdered stuff given to just about every World War Two US Army outfit. It was a monotony of things like salmon, eggs, Spam, chipped beef, bread, mashed potatoes, and beans mixed in with disease carrying flies and dung infested sand. They had no access to roughage in the form of vegetables and fruit, so their gums developed painful gingivitis. Water was a huge issue in the heat and its scarcity meant no showers were available. They were each given half a canteen of water a day to wash and shave. The hot, heavily chlorinated drinking water was barely consumable and it burned their throats.

In the midst of all this misery, the men were subjected to an intense training schedule. Due to the heat, Colonel Gavin was forced to change the timing for infantry training exercises. Infantry training began at dusk and finished at dawn. They trained in infantry tactics designed specifically for Airborne troops. Individual training concentrated on refining hand-to-hand combat skills and bayonet fighting.

Initially an extensive program of jump training was scheduled, but it was soon discovered that an unforeseen strong wind blew across the area for days on end presenting a big problem for parachuting. The high winds and the rocky terrain around the drop zone (DZ) led to a large number of injuries. In the end Ridgway and Gavin were forced limit the practice jumps and focus on tactical ground training. Even with the truncated jump training program all troopers got in at least one practice jump in while at Oujda. Gavin and Ridgway worried that it wasn’t enough. Ridgway personally believed the 82nd was ill prepared and doomed to a disastrous failure in the upcoming Sicily invasion, but outwardly he projected an indomitable optimism and confidence in his men.

“Troops of the 82nd Airborne Division jump en mass, during a demonstration at Oujda, French Morocco, North Africa, on 3 June 1943”

Source: Photo Courtesy of U.S. Army

For the 505, Gavin made sure that training went on. He knew that in combat they would have to jump behind enemy lines and fight as a lightly armed infantry force for extended periods of time without hope of resupply. When dropped at night they would need to find their way to their respective objectives individually and in small groups. Arriving at the objective they could well be disorganized with combat company troopers mixed in with men from the rear echelons.

Gavin believed that to be effective in these situations every man should be able to fight. His orders were that all 505 personnel would take a battle training program. Rear echelon troopers were taught the same fighting skills as combat troopers. Absolutely no personnel were omitted. Despite the Geneva Convention’s stipulations against medics carrying rifles, Gavin even had medics learn how to shoot M1 Garand rifles in the eventuality that they would need to do so in combat.

Bill talked about his training in Africa prior to the invasion of Sicily. He said it was done using models of buildings constructed to be identical to ones they would need to capture in Sicily. This is something documented in several of the histories of the 505 training in Oujda.

Gavin was told of the date of Operation HUSKY (the code name for the invasion of Sicily) a couple of days after arriving in Oujda. So he studied aerial photographs of the area around their planned jump zones and gave orders for the construction of full scale model pill boxes and other defensive structures such as trenches and barbed wire, for training purposes:

“The units maneuvered against the targets with live ammunition, the men moving forward while their own machine guns fired over their heads at the enemy. They learned that weapons sound one way to the firer, but sound completely different downrange. They learned to distinguish American from enemy weapons. They learned to keep their heads down and hug the earth, and they learned to move forward when told. And since the tendency for green soldiers is to fire all their ammunition rapidly, leaving none for the final assault, the men of the 505th were taught to use their ammo wisely.” Source: Ed Ruggero “Combat Jump: The Young Men Who Led the Assault into Fortress Europe, July 1943” 2003, p. 107

“Members of the 82nd Airborne Division load a 75mm howitzer into a Waco glider during training at Oujda, French Morocco, North Africa, on 11 June 1943”

(Notice the troopers are training in full battle dress in the 120 degree heat!)

Source: Photo Courtesy of U.S. Army

Off Duty Drama

On top of the grueling training and abysmal living conditions, the 505 was plagued by a local people left desperately poor by the War. This quote by a 504th PIR trooper gives a good idea how the men felt about their Moroccan neighbors:

“The Arabs swarmed all over us like roaches over food. They wanted to trade with us, or preferably, to steal. They were particularly interested in our sheets, mattress covers, cigarettes, and chocolate. For these things they offered trinkets and fresh food – dates, exotic bread, and meats of dubious origin. We were to post guards twenty-four hours a day in order to keep them from stealing everything we had. Theft was so common that we came to regard the Arabs with almost as much ill will as we did the Germans.” Source: Moffatt Burriss “Strike and Hold” 2000, pp. 29-30

The poverty among the local Arabs was so bad it drove them to take extremely brazen risks. Risks which often had lethal consequences. Bill told a story of when he was off duty at the base with a couple of friends on one typically hot day. There wasn’t much shade to be had in Oujda, but on that day a rare opportunity presented itself. A flat top railway car had been temporarily left on a nearby siding. The flat top offered a good vantage point for observing the comings and goings around the base so not surprisingly it was occupied by a 505 paratrooper on guard duty.

Earlier in the day, Bill and his friends had moved over to take some shade in the flat top’s shadow. As they were whiling away the time, Bill said they saw a solitary figure rippling though a mirage a long distance away, but still within rifle shot. The figure had moved into a restricted area occupied by a supply dump. After a short time the figure started to move off in a direction away from base. To the paratrooper on guard it looked like the figure was in the process of stealing supplies. He jumped up on top of the railway car where he could see him better and taking good aim, he shot him dead. Bill said the figure slumped over on the ground. They all went over to investigate and found the body was an Arab boy of about 12 years. His hands were empty. They couldn’t tell if he had tried unsuccessfully to steal supplies, or whether he was reconnoitering the supply dump in order to make a report to others who were perhaps preparing for a raid.

On June 27th in a letter home Gavin wrote about these incidents:

“This afternoon we are, among other things, having a sniper contest. Fun. These youngsters are getting to be good shots. Regrettably, in the past few days they have practiced on some menacing looking parasitic Arabs. It makes them mad to get shot and we should stop it. It is difficult to sell international goodwill to a private soldier.” Source: Barbara Gavin – Fauntleroy “The General & His Daughter” 2007, p. 33

Moroccan's and Their Fezzes

Bill used to tell another story of how the men would get back at the Arab’s for stealing their belongings. He said the Moroccan men wore a traditional hat called a Fez . Perhaps it looked something like the one pictured below.

North African Fez

Image Source: Wikipedia Commons

Their custom was to carry their valuables consisting of French Franc’s, jewels, watches and so on around in these hats. The paratroopers were trucked around from place to place for training exercises and other activities. Often they went through towns and places like railway stations where they encountered crowds of Arab men going about their business. Naturally the trucks had to slow down to negotiate a path through. That’s when the 505ers would get their revenge by reaching down and grabbing the fezzes right off the men’s heads. The 505ers would retrieve the valuables before throwing the empty fezzes to the ground to avoid the lice they carried. The Arab men would naturally go crazy, but there was little they could do against the well trained and armed soldiers. At times Bill said they actually recovered previously stolen watches and other personal items belonging to paratroopers.

Camels and Mortars

Besides these eye-for-an-eye reprisals, Bill said the troopers designed other ways to make the Moroccans atone for the thefts. Apparently during a day time training maneuver a man was inexplicably leading his camel through the area in which Bill’s unit was practicing mortar fire. They tried to scare the man off by firing rifle shots into the air. It worked and the guy began running trying to get out of the way. In his fright he and the camel became separated with the animal running haphazardly across the field of fire. The men kidded with one another that the randomly moving camel would make good target practice. Eventually, one trooper dared another trooper to take a mortar shot at the camel. He accepted the dare and in a testament to how good the training program was, they scored a direct hit on the camel instantly killing the animal. After the “fun” was over the men were reported and fined. They had to pay the man for killing his camel.

Bill didn’t say how much they were fined, but in another case $25.00 was paid to a local whose donkey had been similarly killed. Source: Phil Nordyke “All American All the Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II” 2005, p. 31.

To be sure, the paratroopers and the Moroccan locals had a difficult relationship to say the least. For all of the pain both groups suffered while living virtually on top of each other there were upsides. Obviously, the Moroccan’s suffered through the process of liberation and foreign Allied occupation. However, it is important to stress with emphasis that they were indeed liberated from the tyranny of the Axis powers.

One of the last letters Colonel Gavin wrote home while stationed in Oujda ended with this positive assessment of the Moroccans:

“I have frequently written to you of the poor quality of the native Arabs. They are certainly that, in addition they are most interesting. As a racial group they are like no other people in the world…The evaluation of a people is made in the last analysis in two ways: by the world at large and by the people themselves. To the world at large, the measure of worth of a racial group is evaluated in terms of their contributions, creative, to the arts, sciences, and welfare of the human race as a whole. To the people, their race is measured by their own happiness and contentment. For this they [the North Africans] do not need material things like cars, movies, etc…..

So despite all that I have said about these people, they are in their own way seeking ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ and not doing a bad job of it at that.” Source: Barbara Gavin – Fauntleroy “The General & His Daughter” 2007, p. 29

On Bill’s part he later became intrigued by North Africa. In 1961 and 1981 (perhaps surprisingly at first thought) he even returned as a tourist. Both times he visited Libya, Morocco, and Egypt. He must have had enough curiosity about the region to want to return. Perhaps he was drawn back by a combination of factors such as: North Africa’s beautiful mountainous landscape; the complexity of its people; and to witness their own notable contributions to civilization.

General Patton Addresses the 82nd Airborne in Oujda

While in Oujda the 505 was visited at various times by several dignitaries. One of these was General George Patton, the famous and controversial commander of the US 7th Army. Bill was present when Patton gave one of his colorful speeches to the troops.

“During the training period, George Patton visited the division at least twice……During these visits, Patton exhorted the paratroopers and gliderists with earthy pep talks. Gavin recalled that Patton began one such talk with an epigram that would become legendary” ‘Now I want you to remember that no sonuva**tch ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making the other poor dumb sonuva***tch die for his country.’.....

….In a final meeting with all of his top Sicily commanders including Ridgway and Max Taylor, Patton was at his theatrical best. ‘In a grand peroration’ Taylor recalled, he turned on us with a roar and, waving a menacing swagger-stick under our noses, concluded: ‘Now we’ll break up, and I never want to see you bastards again unless it’s at your post on the shores of Sicily.” Source: Clay Blair “Ridgway’s Paratroopers” 1985, p. 80.

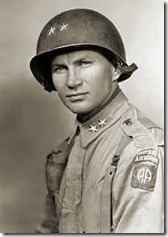

General George S. Patton

Image Source: Wikipedia Commons

In Bill’s opinion Patton was one of the very few generals the US had that was really good. Like other veterans, Bill made mention that even though his commands sustained high casualty rates, he thought the likelihood of survival under Patton was higher because the General’s philosophy was to always keep advancing and never to give ground.

After a visit by Patton and other dignitaries on June 3rd Gavin wrote of his troops:

“Everyone was very complementary about the appearance of our troops today. They are looking fine these days. We have been training and working very hard. I have always thought that these parachute soldiers were very good and of a special cut but I am more than ever convinced now as I see them reach their peak in training. During the past few weeks their training has been very realistic and there have been several casualties. Those we have left are the very best…I will always think that the parachute private is an unusual guy. The saying now is that the AA in the division insignia means ‘Awful Anxious’” Source: Barbara Gavin – Fauntleroy “The General & His Daughter”, 2007 p. 20

82nd Airborne Insignia. Worn as a shoulder patch

Image Source: Wikipedia Commons

“Awful Anxious” is a phrase which seems to encapsulate the spirit of the men after their training in Oujda as this quote expresses:

“Finally it all came to an end and probably no regiment, before or since, was in a better frame of mind to go into combat. The men were lean and mean and at that time would have cheerfully jumped on top of Berlin itself if it meant leaving Africa. To a man they were convinced that combat would be a picnic compared to the incessant weeks of training they had undergone, and with an ‘esprit de corps’ second to none, they were more than confident that they could take on the best the Axis had to offer. History proves that their confidence was more than justified.” Source: Allen Langdon “Ready: A World War II History of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment” 1986, p. 14

The disease, jump injuries, intense training in the heat all took their toll on the 505. The men were naturally toughened from harsh childhoods of the Great Depression. They were further toughened from the brutal Airborne training at Fort Benning, Georgia. Those who survived the hellish trials of Oujda were molded into fearless hardened fighting men – undoubtedly some of the best the world has ever seen.