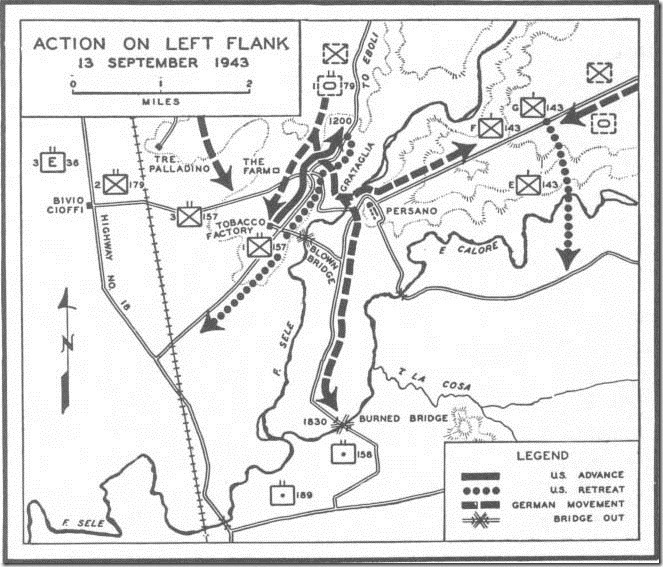

“…there was plenty of artillery going both ways. But the Americans were gradually losing ground. I didn’t stay but few days but from what I saw Salerno made Normandy look like a picnic.” Source: William Clark, letter dated June 13, 1945

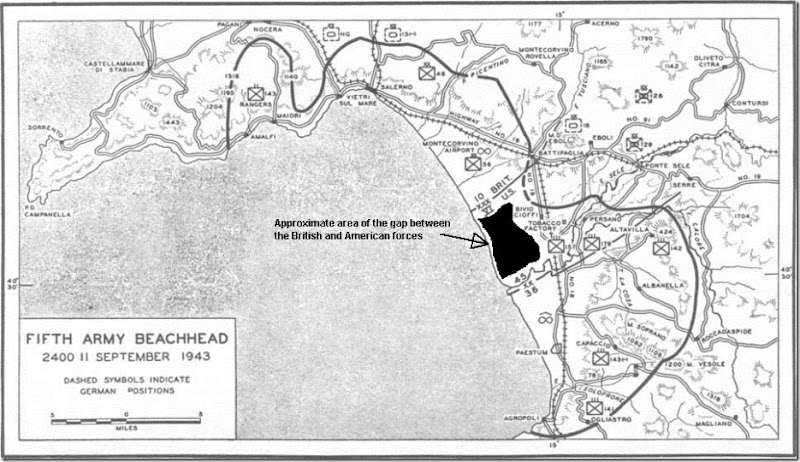

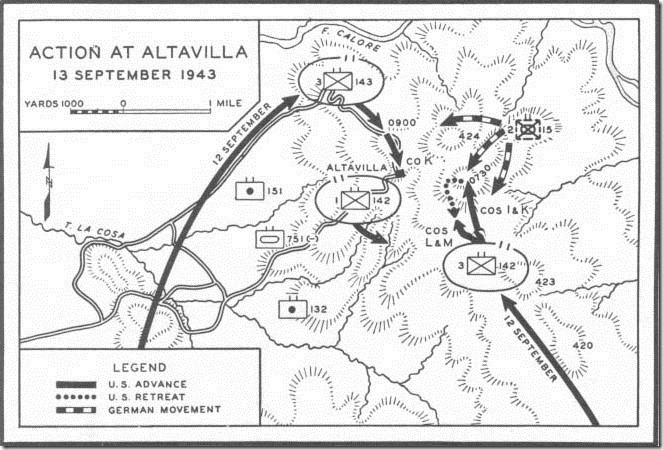

On the evening of September 16,1943 the Allies began to think the Germans might be retreating from the Salerno area. To obtain clues of their intentions and positions the 5th Army had sent out reconnaissance patrols across the Salerno beachhead. Of particular interest to the men in the 504 were the patrols to the strategic hills around Altavilla which returned with reports of intense German artillery, and ominously, 40 panzer tanks on the opposite side of one of the hills. Source: “The operations of the 1st Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry in the Capture of Altavilla, Italy 13 September – 19 September, 1943” Lekson, J., 1948, p. 11

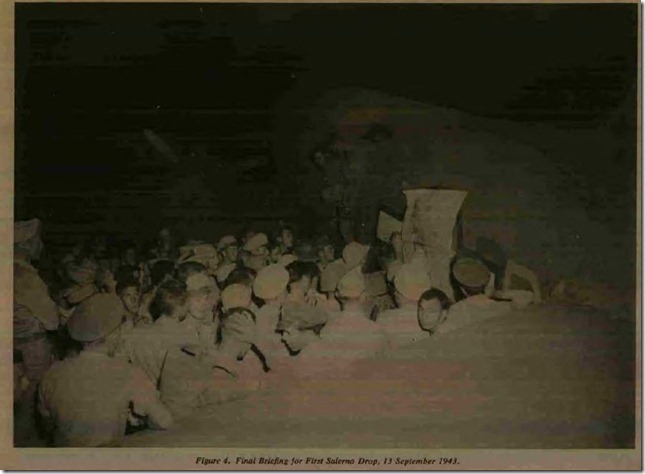

As part of their preparation for the mission to retake Altavilla and hills, the 504 PIR planners were briefed on the terrain and German tactics used to defend the area. The men who briefed them were the survivors of the 36th Division, which lost so many lives in the battles to take, defend, and retake those hills:

“On the slopes of the hills were intermittent streams, dry now, that cut deep gullies into the slopes. Numerous additional erosion features such as dips and gullies marred the hillsides. Many of these had steep sides and narrow bottoms. Trails that went from Albanella to Altavilla followed north on noses jutting from the hill mass. These trails dipped through draws and gullies and often formed defiles as they did so. Lining the trails were tress and stone walls. In places, the trails moved along terraced levels with drops on one side and walls on the other. A profusion of minor footpaths and trails joined the main trail.

Cognizant of the terrain and affected by the heavy American artillery, the Germans had adopted as set of peculiar tactics to hold the hills. Occupying only certain features with outposts and observation parties, the enemy would be alerted as American troops entered the hill mass. From their covered positions would come the enemy main force, which after locating the American forces would maneuver through gullies and ditches to hit the American forces from all directions. Often they were not detected until they were on the positions. With these tactics the enemy had driven out the previous 36th Division attackers”. Source: “The operations of the 1st Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry in the Capture of Altavilla, Italy 13 September – 19 September, 1943” Lekson, J., 1948, p. 15

The peculiar terrain; the way it favored the defenders – and the way the enemy used it to massacre part of the 36th Division – would make taking Altavilla and the hills around it a particularly dangerous – even a suicidal – mission. Several hundred lives on both sides had already been taken. The 504 officers planning the attack must have wondered how many of their own men would perish in this insane but absolutely vital assault.

The Germans still had a powerful incentive to hold the hills behind the Salerno plain. They had fought hard up to that point to destroy the invaders. Now, on the defensive, they would fight ferociously to hold on to the village of Altavilla and its strategic hills to prevent their own cutoff and capture by the Allied forces already beginning to advance from their positions on the Salerno plain below. Moreover, they needed time for their retreating forces to reach Rome and to reorganize while constructing the first of several defensive lines across the Italian peninsula before the British 8th Army could reach them.

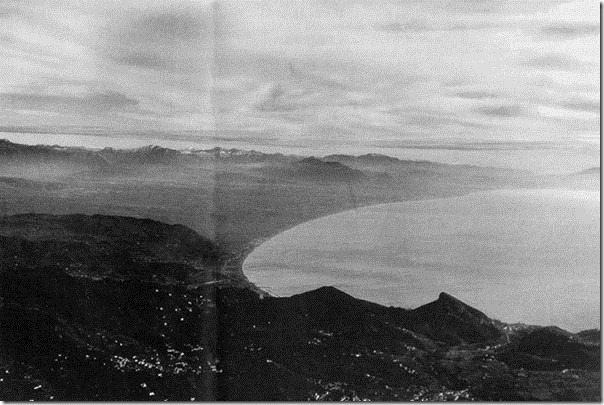

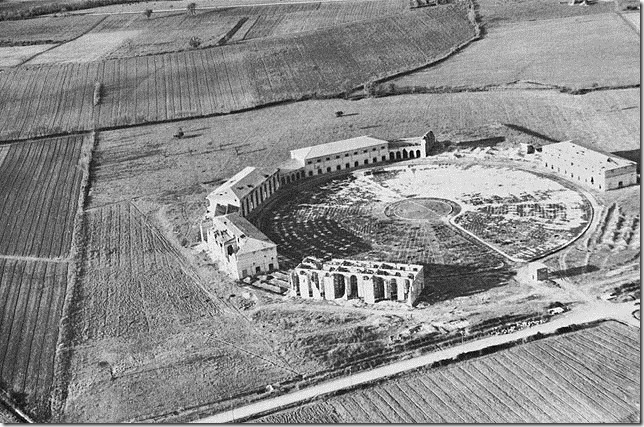

The German view from Altavilla down to the invasion beaches.

Source: NARA

At 3:00 PM on September 16, 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 504 PIR formed a column and began their approximately 8 mile march toward Altavilla. 1st Battalion was assigned Hill 424 to the northeast behind Altavilla. Bill’s 2nd Battalion was to take Hill 344 to the southeast and an “unnumbered” hill between the two east of Altavilla.

Map 1: The approximate route of 1st and 2nd Battalions 504 PIR from Albanella to the foothills near Altavilla

The day was hot. The pace was necessarily fast. They were targeted by German artillery as they crossed the plain to the higher ground. The column was dispersed by the shelling. These were the best trained soldiers of the US Army; physically fit and conditioned from the harsh climate of North Africa. They were rested after the end of the Sicily campaign. In a testament to the severity of the conditions some men passed out from heat exhaustion while the men with heavy mortar equipment couldn’t keep up with the column.

Their route took them though Albanella, but the Germans had already retreated from there. The men doggedly continued their march climbing into the steep hills toward their objectives. Colonel Tucker had made Albanella his headquarters for the mission. But that was a short lived decision – at least for him. Having tried and failed to raise either battalion by radio, he took troopers from the 504 Regimental Headquarters Company and some stray 505 PIR troopers, and went looking for them. He left behind a contingent of personnel to run the 504 headquarters. At around 11:00 PM he made contact with some of Company C on the northwestern side of the unnumbered hill. He discovered they had become victims of the peculiar terrain the 36th Division had described.

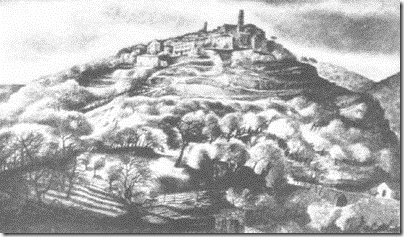

The village of Altavilla from the perspective of the Allies on the Salerno Plain

Source: NARA

After nightfall on the march up into the hills the column broke into fragmented groups of companies and platoons and were unable to reestablish contact with each other. In some cases the cause was men falling asleep while the rest of the column moved on. In others they were attacked by enemy machine guns and became separated. Patrols were sent back and forth to try and reestablish contact. With a paucity of maps these groups became disorientated. Even when some semblance of order was restored, in the rough terrain typified by steep hills, gullies and thick brush, groups in both battalions became confused as to their relative positions. Their disorientation was compounded by an inability to establish radio contact with one another.

When Colonel Tucker eventually found elements of Company C he expected the rest of 1st Battalion to arrive soon. Relying on this expectation, Tucker decided to take Hill 424 with a small force from his Regimental Headquarters Company and the part of Company C he stumbled upon.

The remainder of 1st Battalion had serious problems reaching Hill 424. The illusive key was to find the correct trail, in the dark, which would lead the separated Companies A, B, and the remainder of Company C to Hill 424. The terrain features and lack of maps continued to work against them making reliable progress all but impossible. By dawn Companies A and B managed to dig in on the slopes on the northwest of the unnumbered hill, while the remainder of Company C moved from their location on that hill to the slopes of their objective – Hill 424.

“…and there was plenty of artillery going both ways.” – William A. Clark , 1945

Bill’s 2nd Battalion movements are documented in the Unit Journal of the 2nd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry. In numerous places it talks about the extensive use of artillery during the battle at Altavilla. On page 22 it states:

“About 2100, [9:00 PM] we moved slowly to our high ground objective, which we reached about 0200 [2:00 AM], after numerous stops. Artillery fire was directed at our column throughout the night. The battalion dug in on the high ground assigned to us. The 1st Battalion was on the hill north of us. F Company and most of the 81 mm mortar platoon became detached from us in the dark and were somewhere to our rear”. Source: “Unit Journal of the 2nd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry”. Garrison, C. 1945 p.22.

Shelling in the form of mortar, tank, self propelled gun, and naval gun fire had been frequent and at times a constant presence during the upcoming battle and during the battles for the Hills fought by the 36th Division.

On the way up into the hills Company C trooper, Ross Carter, commented in his must read book, “Those Devils in Baggy Pants”, on the artillery exchanges Bill mentioned in his letter.

“Carey, Lt. Toland, the Arab, and I were lying in a little ditch in a vineyard waiting for the column to move out ahead of us when a shell followed by three others screamed over the hill, hit mere yards from us and exploded, each explosion covering us with dirt and rocks. I’d never known real terror until that moment. The column moved on up the hill under [German] shells moaning high overhead, heading for the beaches….”. Source: “Those Devils in Baggy Pants”, Carter, R., 1951, p. 46

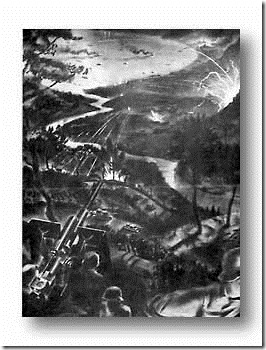

504 paratroopers firing mortar shells on German positions, September 1943

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Dawn came as Tucker’s small force dug in on the hill. The devastating effect of German artillery on the 36th Division was shocking to see. The 504 troopers saw first hand this artillery induced carnage. Ross Carter of Company C was on Hill 424 at the time and later recalled the scene:

“Cadavers lay everywhere. Having seen only a few corpses in Sicily, it was a horrible experience for us to see dead men, purpled and blackened by the intense heat, lying scattered all over the hill. The body of a huge man, eyes bloated out of their sockets, who lay dead about twenty yards from me, had swollen and burst. First lieutenant’s bars were on his shoulders. His pistol belt with open compass case and empty binocular case bore witness to the quality of our equipment: the Krauts had looted them. A broken carbine lay by the body.” Source: “Those Devils in Baggy Pants”, Carter, R., 1951, p. 46

While the 504 were reaching or searching for their objectives, the Germans had become aware of their positions on Hill 424 and on the hillside of the unnumbered hill. In the morning they sent out infantry supported by tanks and mobile artillery pieces. They were seen by Company B from their positions in the heights on the unnumbered hill and by the mixed units from 1st battalion on Hill 424. At dawn Company C sent out two patrols from Hill 424 to reconnoiter to the west and to find the rest of 1st Battalion. Both patrols were repelled by German armor and infantry. After a concentrated mortar strike on Hill 424 the German infantry launched their first attack on the hill.

“The Krautheads began counterattacking. Since only a few of our machine guns and automatic rifles had reached us, it was up to the riflemen and tommy gunners to hold off the assault. The boys lay in their foxholes around the top of the hill and calmly squeezed off their shots. A Kraut machine gun would cackle and then a heavy, deliberate trooper’s rifle shot would lay the egg! The machine gun would remain silent. American riflemen were the best in the world, and our legion riflemen [the men of the 504 PIR] were the best in the army. In about thirty minutes the attack was broken up”. Source: “Those Devils in Baggy Pants”, Carter, R., 1951, p. 50

The Germans also began attacking Company B’s position. After dawn Company B saw Germans coming from Altavilla to their positions on the hillside of the unnumbered hill. They let loose mortar fire on them. The German attack slowed and then retaliated with concentrated artillery fire. After that Germans tanks came from Altavilla and started firing on foxholes occupied by men of Companies A and B located on the slopes of the unnumbered hill. The fire was accurate and killed several men even though they were inside their protective holes. A German infantry attack followed but was defeated. At this time, with their ammunition running low, radio contact was reestablished with artillery units on the Salerno plain. They opened fire on the village of Altavilla. The German’s retreated under the Allied bombardment and launched an artillery barrage of their own on the American positions. Source: “The operations of the 1st Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry in the Capture of Altavilla, Italy 13 September – 19 September, 1943” Lekson, J., 1948, pp. 27 – 29

At 9:30 AM the small force under Colonel Tucker on Hill 424 saw what looked like friendlies on the unnumbered hill itself. All of them abandoned Hill424 to make contact with the men down there. Upon meeting up with them, Tucker ordered Company A to retake Hill 424 with Company C in support. He gave orders for Company B to occupy the unnumbered hill. Company A advanced on Hill 424 and found the Germans moving up the hill to take it. They fought aggressively, driving the Germans down the hill. Source: “Beyond Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2008 p. 94

“…from what I saw Salerno made Normandy look like a picnic” – William A. Clark , 1945

After taking the hill while organizing its defense Company A took stock of the situation. Sergeant Otto Huebner wrote a report on the scene. It mirrors what Ross Carter saw and is perhaps why Bill thought at least in his eyes that Salerno made Normandy look like a picnic.

“The sight on the hill was an unpleasant one. This was the same place that the 1st Battalion of the 142d Infantry, 36th Division, four days previously was finally forced to withdraw after great losses were inflicted on both sides. The hill was infested with scattered dead German and American soldiers, supplies and ammunition. There were machine guns still in their original emplacements, rifles, packs, clothing, ammunition belts, machine gun boxes and stacks of 60 mm mortar shells scattered all over the hill. One machine gun was still manned by two men of the 142d Infantry. The ammunition was gathered up and distributed through the company as soon as possible. Without this ammunition the hill could not have been held. The platoons began digging positions in their sectors. Fox holes dug by the 142d Infantry were improved and used in many cases. Slit trenches were also used in many instances instead of fox holes, because the hard ground made digging difficult.” Source: Huebner, O., “The Operations of Company A, 504th Parachute Infantry in the Defense of Hill 424 Near Altavilla, Italy, 17 – 19 September 1943” 1949 p. 17.

After entrenching themselves Company A came under fire from a lengthy, continuous and extremely accurate tank and artillery attack. Then German infantry tried to take the hill. Company A radioed Company B on the unnumbered hill which managed to call in an artillery strike on the advancing German troops. It stopped the attack, but after a few minutes the Germans resumed the infantry assault. Source: Huebner, O., “The Operations of Company A, 504th Parachute Infantry in the Defense of Hill 424 Near Altavilla, Italy, 17 – 19 September 1943” 1949 p. 18.

“A second counterattack was launched and again the boys picked the Krautheads off like squirrels. Kearny, lying by a thicket, saw some bushes quivering. Covering it with his rifle, he waited. A head stuck up into sight and Kearny shot the left eye out. Schneider, a German-American whose twin brother had been killed in the 9th Division in Africa, had the obsession that if he met enough Krautheads in battle he would at last find the man who killed his brother. He was watching a stretch of ground with another trooper when he saw an enemy machine gun squad advancing to attack. Schneider killed the sergeant and yelled orders in German to the remaining Krautheads. ‘You dumb ********, move to the right, or you’ll all get it.’ They obeyed the orders because they thought one of their own men was giving them. Moreover, in the strain of battle men obey anyone who appears to know what he is doing. Their right now being on the other trooper’s left, he killed three more of them. Schneider then raged out at them again. ‘You dumb sons of *******! I said go to the left. You’re all going to get it if you don’t listen to me.’ They moved to the left in front of Schneider, who killed two more.” Source: “Those Devils in Baggy Pants”, Carter, R., 1951, pp. 51 – 53

The German attack kept coming on despite these efforts. The range was close enough for both sides to use grenades in addition to rifle and small arms fire. Then an unexpected heavy barrage of artillery landed on the German positions and they began to retreat. The Germans lost about 50 men in the fight while the paratroopers lost about 25.

Late in the morning Bill’s 2nd Battalion received orders to move from Hill 344 to the unnumbered hill. According to the 2nd Battalion unit journal:

“At 13:00 the battalion began to move forward to the hill originally assigned to them, but which had been held by the 1st Battalion. We moved out with E Company in the lead, F Company, Battalion CP, Headquarters Company, and D Company. Another climb; it took at least three hours to get everybody there”. Source: “Unit Journal of the 2nd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry”. Garrison, C., 1945 p.22.

In an interview with his friend Herd Bennett, Bill said the Germans had loud speakers in the trees and from these speakers, in an effort to undermine American morale, the Germans played music such as “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny”. Bill said that “the Germans thought they had us beat,…but the music just made us more determined”. Source: Interview with William Clark by Herd Bennett, January 26, 2000.

Company C came up Hill 424 to reinforce Company A. Small firefights broke out on the hill and there were periods of shelling as the Germans probed the Americans for weak points and to keep them penned down. Then at 3:00 PM they launched a massive counterattack beginning with a heavy artillery barrage for around an hour. After that they used machine gun nests to cover the advance of an estimated force of two infantry companies against the positions occupied by Companies A and C. Source: “The operations of the 1st Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry in the Capture of Altavilla, Italy 13 September – 19 September, 1943” Lekson, J., 1948, p. 34 – 35.

The Germans were making good progress up the hill. They broke through the perimeter in places and were close enough to use grenades. The paratroopers responded killing many of them.

The attack went on for two hours. Losses were mounting on both sides. It appeared that the Germans might overrun the hill unless Allied artillery fire could halt the enemy advance. The paratroopers radioed for artillery support, but were only able to receive it from the navy. Due to the close proximity of the Germans to the troopers, the huge naval shells could easily kill men on both sides. The 504 were so desperate, they decided to chance it.

“The word was passed along for the men to get deep down in their holes as the navy began firing. The shell bursts, landing on the northwest slope, seemed to rock the entire hill. The fox holes cracked like class, and the topsoil around sprinkled into the fox holes with every burst. One could hear terror stricken screams coming from the Germans along the slope of the hill, which made one’s backbone quiver.” Source: Huebner, O., “The Operations of Company A, 504th Parachute Infantry in the Defense of Hill 424 Near Altavilla, Italy, 17 – 19 September 1943” 1949 p. 25.

Then massive artillery barrage decimated the Germans and they withdrew.

On the unnumbered hill, Bill’s 2nd Battalion unit journal recalls the bombardment:

“The Artillery became particularly stiff at about 1700 [5:00 PM]. One barrage was constant for 2 minutes. Colonel Tucker set up in our Battalion CP area…many of the regimental staff were casualties. About 1730 [5:30 PM] a messenger came through with information that we were to return to Albanella. This was much to our disgust, as we had the hill and not suffering undue casualties.” Source: “Unit Journal of the 2nd Battalion, 504th Parachute Infantry”. Garrison, C., 1945 p.22.

Click on Altavilla & Hills: 16 - 18 September 1943 to view it in a larger map

(Click on the shapes, lines and blue markers for more information)

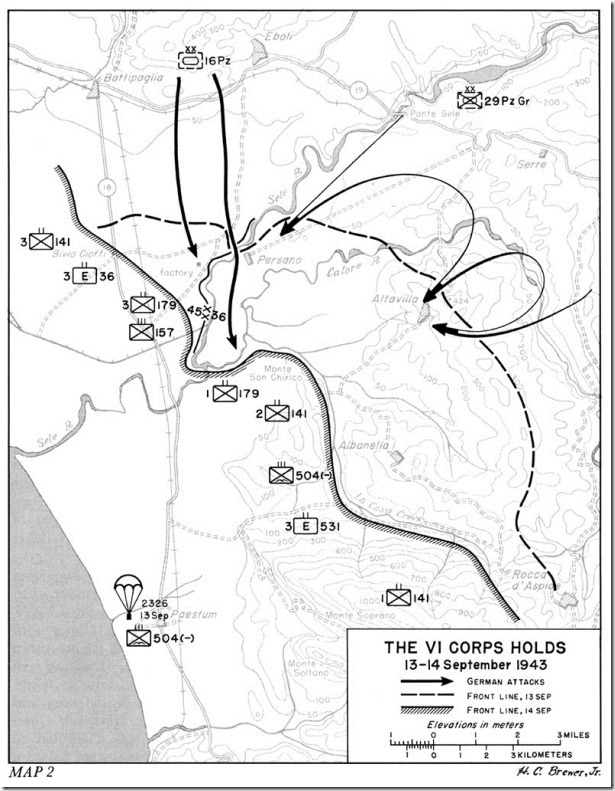

Map 2: The positions of Companies A, B & C and 2nd Battalion from 16 – 18 September, 1943.

“But the Americans were gradually losing ground.”

The situation was bleak for the paratroopers. The Germans had encircled both battalions cutting them off from any retreat. They had sufficient ammunition from the supplies left by the decimated 36th Division soldiers. There was a water source, but food was almost all consumed and they had no way of evacuating the wounded. The Germans continued to shell 1st Battalion on Hill 424 and 2nd Battalion on the unnumbered hill throughout the night. Source: Huebner, O., “The Operations of Company A, 504th Parachute Infantry in the Defense of Hill 424 Near Altavilla, Italy, 17 – 19 September 1943” 1949 p. 25.

Bill mentioned in his letter that the Americans were slowly losing ground. They had been for days before the 504 PIR arrived and even when they reinforced the beachhead the situation was still unpredictable – at least from his perspective as an army private. When he would have learned that the 504 was cut-off and surrounded it probably still appeared that the Americans were losing ground again and that another German counteroffensive was perhaps underway. General Dawley, under General Clark may have thought this was true too:

“General Mike Dawley, commander of the U.S. VI Corps, had received no information regarding Tucker’s two battalions all day. Fearing the worst, and correctly believing that Tucker and his men were now surrounded, Dawley had sent a runner to Tucker with a message instructing him to try to break out while he could still do so. Colonel Tucker ignored the order to retreat to Albanella; his troopers had captured two hills and they were going to keep them. That night, Headquarters Company wiremen ran a sound – powered phone line to Tucker’s command post and General Dawley was patched through. Tucker explained the situation, and Dawley suggested that his two battalions retreat because they were cut off from other friendly forces. Colonel Tucker replied ‘Retreat hell!’ Send me my 3rd Battalion!” Source: “Beyond Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2008 p. 100

Just after mid-night on September 18, Colonel Tucker’s 3rd Battalion (minus Company H which had landed up the coast at Maiori) was assigned to break through to 1st and 2nd Battalions on Hill 424, and the unnumbered Hill. Under very heavy artillery fire from the Germans, Companies G and I traversed the valley from their position of initial attack to the 504 occupied hills. They broke into a run toward the German lines in an effort to get out of range of the artillery.

“After catching our breath and taking count of the men we had left, we moved on Hill 344….Everyone distinguished themselves, knocking out position after position.” Source: “Beyond Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2008 p. 102

At around 3:00 AM 3rd Battalion broke through the German lines and seized Hill 344 below the unnumbered hill. They then made contact with 2nd Battalion on the unnumbered hill. Combat patrols in the morning and then again in the afternoon were made by Company A from their position on Hill 424 to Altavilla and the surrounding area to the north. No Germans were encountered. They had in fact retreated. Food arrived via mule train for the beleaguered men of Companies A and C. Security was set up and the men slept the first time in 72 hours. Colonel Tucker was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his leadership and heroism during the battle for Hill 424. Source: “Beyond Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2008 pp. 101 – 102

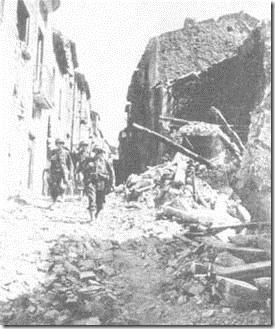

American troops patrol the ruins of Altavilla, September 1943

Source: “SALERNO: American Operations From the Beaches to the Volturno 9 September - 6 October 1943”. p. 79 1990. Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D.C., http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/salerno/sal-pursuing.htm

On the morning of September 19 the 504 was relieved by the 36th Infantry Division. Perhaps at this juncture Bill returned to his Service Company unit in the 505. On Sept 29 the 505th was attached to the British 23rd Armored brigade and moved towards Naples.

“The area in the region of Altavilla for several years had been a firing range for a German artillery school; consequently there was no problem with range, deflection, or prepared concentrations that the enemy had not solved long before the advent of the Americans. Needless to say, hostile artillery and mortar fire were extremely accurate and capable of pinpointing with lethal concentrations such vital features as wells, trails, and draws. During the three days that the 82nd occupied the hills behind Altavilla, approximately 30 paratroopers died, 150 were wounded, and one man was missing in action.

The majority of these casualties were cased by the enemy’s artillery fire. Enemy casualties were, judging from the number of dead left on the field of battle and from information divulged by prisoners, several times those of the troopers. Four separate and distinct attacks by the enemy, launched from the North , east and west of 504 positions were driven back with heavy casualties resulting for the Germans. Capture of Altavilla and Albanella allowed for the Fifth Army to move northward toward Salerno and Naples.” Source: “The Saga of the All American” Dawson, F., 1945 Italy section

“The drop zone at Salerno had already been the scene of action the night before, September 13, when the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 504th had jumped into Italy, their 3rd Battalion arriving on LCIs. The 504 had fought like hell and turned the tide of the battle in favor of the Fifth Army. The beachhead was saved and the Americans were not thrown back into the sea.” Source: “Jump Commander” Alexander M. and Sparry J., 2010 pp. 111 – 112.

“There was still plenty of work to do, however. First they needed to push the Germans back and break out of the beachhead. ‘We organized right away and they marched us up into the mountains to relieve the 504 at Castel San Lorenzo, a little village on the mountainside east of the bay. It looked like they had a hell of a fight. There were dead Germans lying all over the place.’” Source: Jump Commander” Alexander M. and Sparry J., 2010 p. 112.

Below is the Payroll for Service Company 505 September 1 – 30, 1943. Bill’s name appears on line 17. From this it would seem that he was with the 505 during the Salerno battles. To the contrary, and in addition to the evidence in the previous posts, Bill told his friend Herd Bennett that he could have volunteered for Anzio with the 504th, but had decided not to:

“Bill indicates that the 504th Regiment of the 82nd Airborne was still in Italy “at the hell hole known as the ‘Anzio Beachhead’. Bill stated that he could have volunteered to jump at Anzio as he had done at Salerno, but he had not. Bill advises that when the 504th finally joined the 505th Regiment in England, he did not ‘know half a dozen men, because they had all been killed and replaced at Anzio’.” Source: Interview with William Clark by Herd Bennett, January 26, 2000.

In 1996 during my time with Bill he said that he had a lot of good friends in the 504 and it was sad to not see them when they joined the 82nd in England.

Payroll for Service Company 505 September 1 – 30, 1943.

© Copyright Jeffrey Clark 2012 All Rights Reserved.

![Payroll-Ser-Co-505-Sept-1---30-1943_[1] Payroll-Ser-Co-505-Sept-1---30-1943_[1]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/-5BLI5eKNw08/UGHXc4nkhbI/AAAAAAAADMs/XgKJO8MEQok/PayrollSerCo505Sept1301943_4.jpg?imgmax=800)

![Italy-Proposed-and-Actual-missions_t[1] Italy-Proposed-and-Actual-missions_t[1]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/-mmNVT7jovec/UFJXJ8x4NiI/AAAAAAAADKY/h_BWTibNftY/Italy-Proposed-and-Actual-missions_t%25255B1%25255D_thumb.jpg?imgmax=800)