Bill said that he stayed in Casablanca for one week before boarding a train to the location of their North African training base in Oujda, French Morocco. The date that the Division began moving to Oujda was May 12, 1943. Bill arrived in Casablanca on May 10, so his train probably departed on May 17 or soon after.

The trip lasted about 48 hours so Bill would have arrived at Oujda sometime on May 19.

Here’s a humorous excerpt about the train journey from “Ready: A World War II History of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment” by former 505 WWII paratrooper, Allen Langdon.

“…most of the regiment went by rail and so got its first introduction to that famous (or infamous) mode of travel, the French 40 & 8 railroad car, – in this case a rickety railroad that must have been the inspiration for the old “Toonerville Trolley” comics. While on this trip 505ers got their first look at some of Hitler’s supermen, the equivalent of whom they would be facing in the near future. At some point in the desert the train stopped on a siding directly opposite a train load of big, blond, bronzed Afrika Korps prisoners of war. Riding on top of each of the box cars was an equally big, inky- black Senegalese soldier with a tommy gun. One German who spoke English began talking to the troopers and the following conversation took place:

Afrika Korps POW: “Where do you Americans think you are going?”

Paratrooper”: “We’re going to Berlin.”

Afrika Korps POW: Well, that’s fair enough, We’re headed for New York.” Source: “Ready: A World War II History of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment” Allen Langdon, 1986, p. 9.

Here’s a picture of a Toonerville Trolley comic strip from 1917 to give some context to what the paratroopers were reminded of by the French trains.

Image Source: Wikipedia Commons

Here’s a richly descriptive account from a trooper who made the journey not by train, but in a convoy of trucks. I felt compelled to include it since it captured so well the magnificence of the Moroccan countryside, the ancient culture of the native people, and the mindless destruction of both by the war.

“…On the trip to Oujda we passed through some of the most wonderful country imaginable. There were grain fields, olive orchards, citrus trees, vineyards, flowers, snow capped mountains, pretty rock formations and unique cities. We saw the antique methods of farming with plows made of scraps pulled by oxen. Some of the plows were made of wood, which is very difficult to find anywhere in North Africa. All of the natives went to the fields very early and as they marched along with that slow gait of theirs they all chanted the religious music that they so well love. In several places we saw them harvesting the wheat by cutting it with hand made scythes and tying the bundles with the straw……..”

“We visited several wineries and sampled some of the famous wines, but the places were so filthy that we almost became sick. We gathered some apricots, walnuts, peaches, grapes, lemons, limes, oranges, almonds, plums and dates and had a real feast along the route. We saw crude little French trains as they sped along at twenty m.p.h. We were much amused by the huge charcoal burning busses that hauled fifty or sixty passengers. Most of them broke down every few miles, but the people did not mind that at all. We saw the ‘Wadis’ (creeks) running wild at the foot of the mountains as the melted snow came down in torrents.”

“We passed by some of the olden castles and cities and soon got into the battle areas where we began to really see what a war does to a country. We began to see roadside graves marked with the fallen soldier’s helmet or rifle. We passed a few neat cemeteries, which were kept up by the Arabs. We began to see the destroyed tanks, trucks and planes and other impedimenta. We were amazed at the amount of equipment that Jerry had deserted in his hasty retreat. The fields were covered with his supplies. Some of the cemeteries were almost beautiful, with ornamental walks and gadgets made by the soldiers….” Source: 0f All American All the Way: The Combat History of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II, Phil Nordyke, 2005, pp. 28 - 29.

Bill’s EGB unit set up camp a couple of miles away from the 82nd Division’s main encampment. I’m not sure why they set the EGBers so far away except maybe to ensure they didn’t get in the way of the Division’s main training activities. The men of the EGBs themselves trained hard and stayed in excellent shape. They were subjected to the same demanding training and adhered to the tough discipline which typified life in the 82nd Airborne.

Bill said he stayed in Oudja for one month. Not all of that time was spent in the EGB. In fact after arriving, his time as an EGB man was to last only seven more days. His big break came on May 26, 1943 when a Special Court Martial was held at the 505th Regimental Headquarters at the Oujda base.

Documentation of this event was found in a Morning Report for the 505th PIR at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri.

The primary order of business at the Special Court Martial was assignment of men many of whom were presumably from EGB’s (although that is not indicated) to companies within the 505’s evolving Table of Organization.

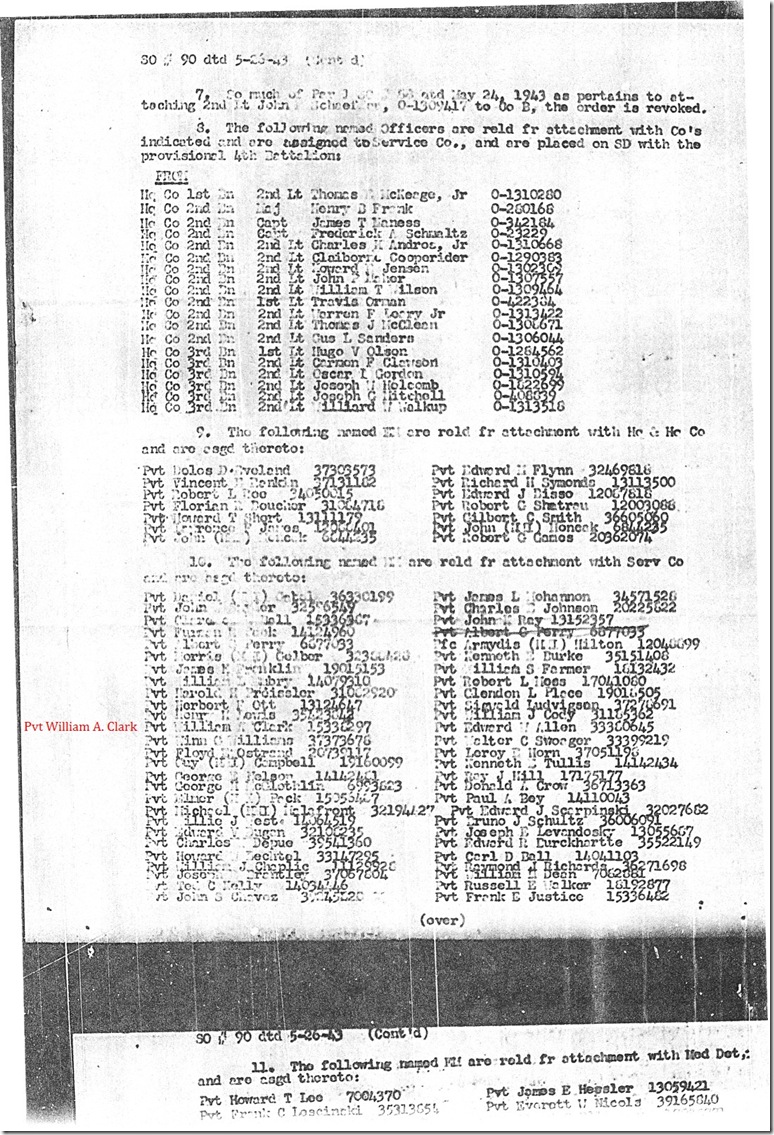

Below is a copy of a portion of the Special Court Martial (Special Order Number 90). It is dated May 26, 1943.

Source: Morning Report 5/1943 for the 505th PIR, National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri

As per Point 1 on the first page, the Special Court Martial met at the 505 Headquarters which was stationed at the Oujda base. It is unclear if Bill was present for the event or whether he received the orders for his assignment later. Direct reference to him can be found on page 2 above.

Under point 10 it states "The following named EM are reld fr attachment with Serv Co and are asgd thereto:”

About half way down the page in the first column is the entry for Bill:

“Pvt William A. Clark 15338297”

Pvt William J Cody is listed in the second column almost directly across from Bill’s entry. In the blog post on Bill’s training I talked about William (Eagle) Cody as being a good friend of Bill’s and one with whom he corresponded after the war.

There are several other names that are familiar to me. One in particular is Pvt Gilbert C. Smith. His name appears in the second column of Point 9 being assigned to Regimental Headquarters Company. Twelve days later on June 7, 1943 Gilbert was killed while on duty at Oujda. His company was making a practice jump as part of their training. Gilbert’s parachute failed to fully open. The trail of its white silk followed him to the ground in an accident known as a “streamer”.

There’s a lot of interesting information in the document. From it some observations and can be made and conclusions inferred. With the exception of the few soldiers listed in points 3, 4, 5 and 6, the majority of the officers and enlisted men are being assigned to Regimental Headquarters, Headquarters Company, Service Company, and the Medical Detachment for the 505th PIR. The EGB personnel were to be used as replacements when men were injured or killed. There are too many names listed to conclude that these were EGB men replacing troopers injured in training, or those suffering from diseases – like dysentery which was prevalent at the time. Moreover, combat training jumps (which caused by far the most injuries) only began on June 5, 11 days after these assignments. Instead I believe unless where companies are indicated they were EGB men being assigned to the 505 for the first time.

Furthermore, Point 8 States:

“The following named officers are reld fr attachment with Co's indicated and are assigned to Service Co., and are placed on SD with the provisional 4th Battalion.”

SD means Standard Duty. The word “provisional” likely refers to the planned future designation of a fourth battalion. In the table of organization for the 505th there were three battalions – all of them combat units. 1st Battalion contained Companies A, B, and C; 2nd Battalion contained D, E, and F; while 3rd Battalion contained G, H, and I. The rest of the table of organization consisted of Regimental Headquarters, Headquarters Company, Service Company, and the Medical Detachment for the regiment. Perhaps it was under consideration at the time of this Court Martial that these companies were to be later assigned to 4th battalion 505 which was only provisional at that stage.

Notably, all of the officers in Point 8 are being moved from the Headquarters Companies of the three combat battalions to the 505 Service Company. This is a significant transfer which together with the assignment of the enlisted men in Points 9, 10, and 11 seems to indicate that the regiment was undergoing a reorganization of its existing structure. It’s as if the responsibilities relating to servicing an airborne regiment were being taken from the individual battalions and centralized into one new Service Company.

Based on these observations, it seems reasonable to conclude that even at this late point in the 82nd Division’s activation as a front line fighting force the organization of the 505 was still being developed. This is supportive of the fact that the concept of Airborne Warfare was at the time still in its infancy.

In this regard, the Special Court Martial document quietly underscores the extreme risk facing these early paratroopers. Not only would they soon be facing a well trained and superbly equipped enemy behind their lines, but the very principles of Airborne Warfare were still being formulated and had yet to be proven in actual combat operations. I will come back to this reality and its tragic consequences in later posts on the Sicilian Campaign.

Most if not all paratroopers in the 82nd Airborne wouldn’t have been concerned in the slightest by such considerations. That airborne warfare was a particularly dangerous endeavor was well understood and even embraced by the average paratrooper.

Undoubtedly Bill would have been overjoyed at his finally being selected for assignment to the 505 Service Company. No longer would he languish under the dubious banner of the “Easy Going Bastards”.

I can picture him now after receiving the assignment orders. Head swimming with unbelieving excitement he ducks down into the pup tent which he thought would be his home for forever. His hands fumble as they hastily grab a dusty duffle bag, half empty with meager belongings. He turns to the men who have gathered around, trading farewell jibes with those he will leave in EGB limbo before rushing over to the road to bum a ride to his new digs. No ride appears and in his impatience and despite the heat of 120 degrees he begins eagerly traversing the two miles separating the EGB encampment and the main base where the 505 are bivouacked.

It was to be the beginning of a long assignment with Service Company. But Bill’s joy would have been short lived. The time in North Africa was to be extremely difficult. The location of the camp, a grueling training schedule, outbreaks of dysentery and the climate were to conspire to wash a lot of men out.

In upcoming posts I will relate the stories of Bill’s time in North Africa. Some of them are funny, others are dramatic or tragic, and still others are more than a little adventurous.

Stay tuned.