For months now I’ve been trying to piece together the dates of Bill’s activities after he finished Basic Training to when his unit shipped overseas. Until recently there wasn’t much to go on, but now it’s possible to reconstruct most of this information.

Bill finished Basic Training at Camp Wheeler, Georgia by the end of January, 1943 and quickly made the 100 mile journey across state to Fort Benning. He had to get there before Monday, February 1st, the start of a 4 week course in parachute training (AKA ‘Jump School’). He arrived in time and graduated on Saturday, February 27th as a fully qualified Paratrooper.

Next he was assigned to train as a Rigger and Parachute Repairman (MOS 620) in Fort Benning’s Parachute Rigger School graduating on or close to Wednesday, March 24th. It was an advanced graduate course where he learned specialist skills in the inspection, maintenance, repair, and packing of parachutes.

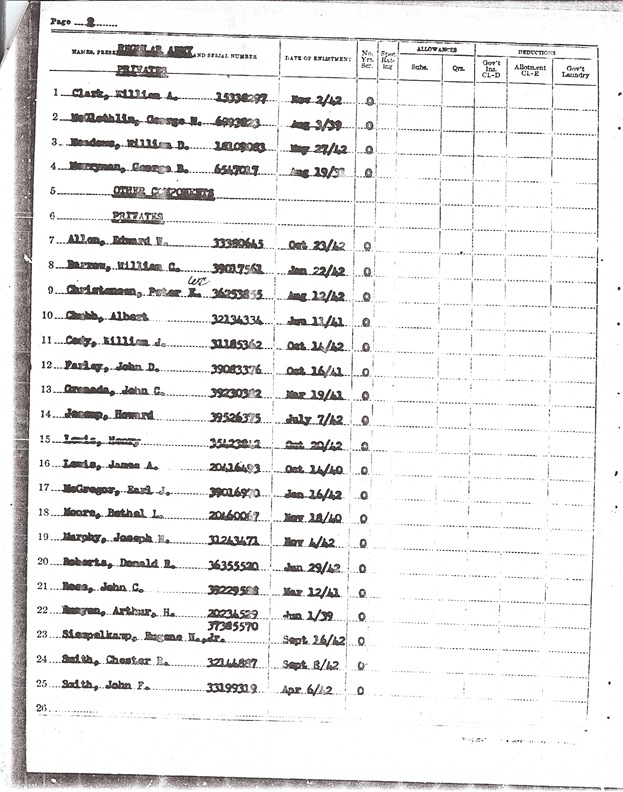

These dates and assignments are deduced from: the letters Bill wrote home during Basic Training; his discharge papers; what is known about Jump School; and the only new trace of information found so far about his time in Fort Benning – a Partial Payment PAY ROLL dated March 24, 1943.

The pay roll is for the Enlisted Parachutists Riggers Class #33. They were assigned to N Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Parachute Training Regiment.

There are three pages to this document which appear below. Click on each page to make it bigger.

Bill is the first man listed on line 1 of Page 2:

Name: Clark, William A.

Serial Number: 15338297

Date of Enlistment: Nov 2/42

Number of Years Service: 0

I recognize the name of a close friend of Bill’s listed on line 11 of Page 2: “Cody, William J.” His nickname was ‘Eagle’. Eagle was eventually assigned to the same unit as Bill: Service Company, 505th PIR. He survived the war, ending up in Berlin with Bill where both of them were assigned to occupation duty in the 82nd Parachute Maintenance Company. They corresponded after the war until at least 1946.

Partial Payment PAY ROLL

March 24, 1943

Enlisted Parachutists Riggers Class #33

N Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Parachute Training Regiment

(Bill Clark Listed on Line 1)

Page 3 Partial Payment PAY ROLL

Significance of the Partial PAY ROLL Document

On lines 10, 11, and 12 of Page 3 the document states:

“The amount set opposite the name of each enlisted man on the payroll have been determined in accordance with the provisions of paragraph 10b, AR 345-155 to include parachutists pay and have been charged against him on his service record.”

Despite this no dollar amount is entered for any of the men. My research sources have indicated that there was no unit roster for Company N, 3rd Battalion (Class #33). It’s probable that this partial payroll served not as a record of the men’s pay, but as the unit roster for those men graduating from the Parachute Rigging Class #33 on March 24, 1943. Furthermore, the fact that the payroll is a partial payment indicates that his parachute rigger training class ended on March 24.

Length of Basic Training 10 – 12 Weeks (Early November - January 29, 1943)

Basic Training programs in World War Two took anywhere from 8 to 15 weeks to complete depending on the particular unit to which a soldier was assigned. So how long did Bill’s take?

His last correspondence from Camp Wheeler is post marked January 27, 1943 on the envelope – the same as the internal date on the letter. Bill’s discharge papers state he received his Parachute Wings (aka ‘Jump Wings’) in February, 1943. The corresponding Jump School program lasted exactly four weeks. For Bill to have written a letter on January 27 from Camp Wheeler and graduate from Jump School some 100 miles away at Fort Benning in February must mean that he completed Basic Training close to the very end of January and probably on Friday, January 29th.

He would have needed to start Jump School by Monday, February 1st at the latest to finish the four week program and earn his Jump Wings in February. It would take time to cover the distance from the two camps, say about a day, with potentially some time needed to get organized on either end of the journey. So to make the start of Jump School on February 1st, Bill probably left Camp Wheeler by January 30th at the latest.

Following this logic, since he enlisted on November 2, 1943 and it took say a couple of days to get to Camp Wheeler from Fort Campbell, Kentucky Bill’s basic training at Camp Wheeler would have taken most of November, all of December, and all of January; a period that lasted between 10 and 12 weeks.

Jump School 4 Weeks (February 1 – 27, 1943)

Parachute training was designed to be an impossibly difficult mental and physical test of a man’s strength of will. It was a four week course comprising of Week A, B, C, and D. It was so intense that only half of all recruits that started it would ever earn their Jump Wings.

To become a paratrooper in WWII was a huge deal. Even those veterans I’ve interviewed who never made combat jumps during the war, but who made it through Jump School are immensely proud of their accomplishment. An indication of how tough Jump School was is that the other paratroopers who did make combat jumps treat these non-jumper graduates with a measure of respect.

Week A of the course was used to weed out those who were physically weak and without sufficient character to become a paratrooper. It consisted of grueling physical programs that made any boot camp experience of WWII look like a picnic. These programs consisted of constant, unceasing exercise for at least nine hours straight each day. They included rope climbing, pushups, long runs day and night, judo training, tumbling exercises for breaking your fall during a jump, and brutal hand-to-hand combat fights emphasizing silent killing techniques.

As if this wasn’t enough, men were regularly and frequently pulled aside by officers and drill sergeants for minor infractions and often for no reason at all; and then ordered go for a run or to do 30, 50, even 100 pushups – sometimes one armed. No one was allowed to walk. They had to run everywhere. All this was designed to push the men beyond their physical and mental limits.

To quit of one’s own volition meant swift expulsion from the Airborne. If a man failed to achieve at an established level of performance he was out. There were no second chances. Any man who quit or couldn’t keep up was immediately escorted off the base. Most washouts occurred during the first two weeks.

Week B aimed to teach the trainees how to parachute. They learned the function of the parachute: how to exit the aircraft and properly position their bodies during the jump; how to steer while in the air; how to avoid injury upon landing; and when to use the main chute strapped to their backs versus the reserve chute on their chests.

They used wooden models of C-47 airplanes to learn the sequence of making a parachute jump as part of a ‘stick’ or team of 18 paratroopers. They drilled on getting it faster – down to at least two men per second. The quicker they exited the closer together they would be on the ground and therefore, the better their chances of functioning as a fighting unit and surviving in combat.

During Week B, the hard physical training programs of Week A intensified in difficulty, washing more recruits out.

Week C kept up the impossible pace of the physical exercise and repeated the jump training. On top of this, the main objective during this week was to test each man’s courage. They learned to jump from two towers; one of 250 feet and the other of only 30 feet.

In the 250 foot tower exercise each man was put in a harness connected to a parachute that was fastened to a strap and hoisted up using a pulley system to the top of the tower. They were let go and the parachute would open. Most men made it easily.

The 30 foot tower was more of a problem. The trainees had to climb to the top of the tower and were ordered to jump from a model of a C-47 airplane door. They were harnessed and connected by a strap to a cable that was terminated in such a way so as to catch their fall before they hit the ground. It was so close to the ground that a lot of men instinctively balked at the unnatural situation and could not trust the cable to terminate properly when their time came. If they failed to jump they had to walk back down the tower. Perhaps surprisingly to those of us who never did it, the 30 foot tower exercise washed a lot of otherwise physically capable men out of the program.

An additional requirement during Week C was for each man to learn how to pack his own parachute. The men were incented to pay close attention and learn this skill very well because in the final Week D of the program they were made to jump with the parachute they had packed. If a man’s chute failed to open – and there were some that didn’t – he would have only himself to blame for his death.

Week D continued with the physical torture of the previous weeks. On top of that the trainees were required to make five jumps. They would have to confront and overcome their fear of heights, parachute failure, and death – all a full five times. The first jump took place on Monday and the last on Friday. Monday’s was the hardest because it was their first time jumping and most of them had not even been in an airplane before. After each jump, with their bodies and brains spent from the constant exercise, those that were left had to pack their parachutes again for the next day’s jump.

At the end of the week each surviving man graduated from Jump School. The graduation ceremonies were held on a Saturday. The new Paratroopers were presented with their silver Jump Wings which they wore pinned to their left breast. They were allowed to wear their jump boots (which had been issued during Week A) off of the training base and to tuck their pant legs into them. Known as ‘blousing', this was something which distinguished them from all other US armed forces personnel.

On Saturday February 27, 1943 Bill had graduated earning his Jump Wings. Mentally disciplined and physically toughened, he had overcome his fears and proven himself worthy. Now he was a Paratrooper; an elite. He was a member of the best team of soldiers America would produce in WWII. The realization filled his young mind with enormous pride – and ‘balls’.

Parachute Wings aka ‘Jump Wings’ issued to Paratroopers upon completion of Jump School

Image Source: Wikipedia Commons

Parachute Rigger School 3 Weeks (March 1 – 24, 1943)

Bill’s discharge papers state that he attended the “Parachute Rigger School, Fort Benning GA Feb’ 43”. His attendance at the Rigger School is corroborated by the Partial PAY ROLL document. However, it is not possible that he was trained as a Rigger before completing Jump School. Every want-to-be paratrooper had to complete Jump School first before anything else could happen. With Bill’s Basic Training finishing at the end of January, the only time he could have attended a Rigger course was to do it at the beginning of March after he completed Jump School.

So why does Bill’s discharge record say that he attended a Parachute Rigger School in February, 1943? The answer lies in the way men were selected for occupations in the 82nd Airborne during the war.

Their military records (if they had any), Basic Training evaluation reports, and their skills acquired during civilian life were all reviewed to determine the unit they would be assigned. Besides combat troopers, there was a need for clerks, cooks, typists, mechanics, illustrators, polyglots (with German and Italian in high demand), drivers, carpenters, medics, and so on. Men with skills in these and other areas were tagged for assignment to a Service Company in a parachute regiment.

Bill’s Separation Record gives a description of his work and skills before the war as a Back Tender at the Aetna Paper Mill. Being skilled in controlling and adjusting the machines used in making paper and manipulating the paper sheets does correspond to repairing, and maintaining things. Parachutes, like paper, are essentially two dimensional objects . It is not a big step to construe that the skills of a back tender could be useful in repairing, maintaining and packing parachutes.

When Bill arrived at Fort Benning, someone likely looked at his civilian background as a paper mill back tender and decided that he had much needed skills relating to parachute rigging, repair, and packing. They assigned him to the Parachute Rigger School in February. This school taught him the Jump School course first in February. After he graduated he completed the Rigger class by March 24th. Judging by the partial payroll date it probably started on Monday March 1st and lasted for around three weeks.

Parachute rigging had always been part of the Fort Benning Jump School training program. At first men had to learn everything about parachuting, including: how to jump; load equipment; and inspect, repair, and pack chutes. But as the Jump School graduates swelled to fill the ranks of the growing number of US Army Airborne Divisions the loading of equipment and advanced skills of parachute inspection and repair were dropped from the course. These skills took too much time to learn which slowed the training process down. Ultimately the decision was made to design an advanced course on packing and maintenance of parachutes. This is the course which Bill took.

This sequence of training corresponds with historical sources like this one documenting the history of the parachute rigger course used in WWII:

“In a sense, this was a post-graduate course to the main parachute jump training. The scope of the rigger training program was described in these words: ‘At the riggers school the men are trained as specialist maintenance personnel to inspect and to repair parachute equipment and to build new types of rigging, parachute containers and harness[es] for special use.’ At the end of the war the Riggers Course continued to be given, along with the Parachute Course (Basic Airborne Course)…”

- History of the Development of Airborne Courses of Instruction at the Quartermaster School 1947 – 1953, page 6

Assignment to an EGB Battalion (After March 24 – April 17, 1943)

By January, 1943 the 505th PIR was already fully manned and staffed. So after graduation from the Rigger School Bill was assigned to an EGB battalion within the 82nd Airborne, where he continued training as a paratrooper. This would have encompassed a period from March 24th until April 17th; around the time the 82nd Airborne began moving out to deploy.

By the end of April, 1943 there were some 4,000 EGB personnel in the 82nd Airborne, including: orderlies, medics, stenographers, clerks, cooks, carpenters, truck drivers, parachute riggers and combat soldiers. Men in an EGB battalion were replacement troopers yet to be assigned to a unit. They would have to wait until someone died or was injured to take their place – not a thought Bill relished. And not one relished by those men already assigned to units. No one wanted anything to do with his potential replacement.

EBG men referred to themselves as “Excess Government Baggage”. Men of assigned units called them “Easy Going Bastards”.

The name calling aside, Bill wouldn’t have been happy about his predicament. He had trained just as hard as everyone else and was a thoroughly qualified paratrooper. He was just one month too late in finishing Jump School and didn’t make the final intake of assigned troopers in January.

Bill’s training as a Rigger would mean he would eventually be rigging parachutes and jumping into combat as a show of confidence that he’d packed the chutes correctly. He would have to wait for an opening in the Service Company of the either the 505th or 504th PIR for that to happen.

His time in the EGB battalion included combat training in addition to continued parachute rigging. He trained in stealth killing; evasion techniques for war behind enemy lines; hand-to-hand close quarters combat; and as a rifleman in attack and defense of key objectives.

By the end of it all he was a razor; conditioned to respond to any physical threat on instinct and with immediate lethality.

On April 17th, the 82nd Airborne Division was on the move. They assembled at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Bill’s EGB unit was with them. On April 20th, they made a rail journey to Camp Edwards, Massachusetts. They stayed there until April 28th when the Division caught trains to the Port of New York where the men boarded ships.

Before dawn on April 29, 1943, 67 years ago to the day of this blog post, Bill’s ship the USS George Washington set sail. Unbeknown to him he was bound for Casablanca in French Morocco, North Africa and the beginning of his war.

Image Source: Wikipedia Commons

© Copyright Jeffrey Clark 2009 - 2010 All Rights Reserved.

Hello Jeff.... I'm trying to conduct some research concerning a WWII vet who may have served, or worked with, the 82nd Airborne... finding his discharge papers would be extremely helpful for me. Where did you find your uncle's papers? You can contact me at discoduck7@hotmail.com.... my name is Ian Hill. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteGood morning. I'm trying to find records on my father. I know he was a paratrooper w/the 82nd Airborne. I know he got his Jump Wings. I think he did basic training at Ft. Benning. I have his SS#. I know he enlisted 20 Apr 1944 at Ft. George D Meade, MD. How do I obtain payment record, discharge papers and separation record?? He died in 1973. I wonder if anyone is still alive that he served with? You can contact me at bup-bup@juno.com. Thank you, Kim Owen

ReplyDeleteI am looking for any information on my father who was at For Benning Ga. during the years 1943 to 1945 from what I gather he was an instructor there. My fathers name was Elroy Bennett and I do have his service number if that would help.

ReplyDeleteI know from the paper work that my father went over seas in Jan. 1945.

If you can not give any information could you send information on how I could get information on him. He died in 1984 and his children would like to fill in the missing pieces of his life. Thank you, Karen Bennett (Quandt)

This blog post provides fascinating insights into Bill's military training and career.

ReplyDelete