The Journey Home

The date of Bill’s departure from Berlin cannot be known with absolute certainty. His Honorable Discharge states an ASR Score of 92 points on September 2, 1945. The history of the 82nd PMC provides specific dates for the departure of its men from Berlin. Those with high enough ASR Scores left in groups beginning September 7:

“On September 7, 1945, six men with points above ninety, who had signed over, and one person who unfortunately missed the original shipment home because of being in the hospital, now departed for return to the U.S. Since First Sergeant Legg was included in this group, Tech Sergeant Butenhoff was now made acting First Sergeant”. Source: Author Unknown, “82nd Airborne Division: 82nd Parachute Maintenance Company” Section 1 Unit History, Date unknown, p. 15

It is unlikely that Bill was one of these men. Six of them had “signed over” meaning they had been transferred from the 17th Airborne Division to the 82nd Airborne Division. That clearly had not happened to him. He was not the man who missed the original shipment, since he did not qualify at the time to return home with the men of 85 points or above. As told in a previous post, “The Postwar Points Discharge Plan”, Bill took a “shot on points” (a lottery which if a man won, increased his ASR Score sufficiently to allow his early discharge) late in his stay in Berlin. He liked Berlin so much that he delayed the “points shot” and when he took it, he won.

More groups of men left Berlin in the first half of October:

“On October 10th, one man departed from the Company for his return home. The next day, six enlisted men and two commissioned officers departed for the return trip home also. Included in this group was acting First Sergeant Butenhoff, so now Tech Sergeant Moen was give (sic) the responsibility of being First Sergeant. Following these, were five more men and one officer leaving on the 13th of October 1945.” Source: Author Unknown, “82nd Airborne Division: 82nd Parachute Maintenance Company” Section 1 Unit History, Date unknown, p. 16

These were the last groups of men to leave the 82nd PMC before the 82nd Airborne Division was relieved of occupation duty in Berlin on November 19, 1945. So it is most probable that Bill was one of the groups beginning their journey home on either October 10, 11, or 13, 1945. This timeframe fits with the date of his departure from Europe, stated on his Honorable Discharge, of November 1, 1945. These dates also fit with the written account of his journey home given in an interview with his friend, Herd Bennett:

“From Berlin [after he won the ‘shot on points’] he went by train back to Frankfurt, Germany and from there to Antwerp, Belgium. From Antwerp he was sent back to the United States and arrived in New York City in November of 1945. From New York City, Bill was ordered to Indian Town Gap, Pennsylvania and in November of 1945 he was there discharged. He took a train to… Cincinnati Train Terminal where he caught a bus to Hamilton, Ohio. In Hamilton, he went to his aunt’s house and she drove him to his boyhood farm home on Dixon Rd… Bill states that he wanted to surprise his parents with his return from W.W.II, and he was successful.” Source: Herd L. Bennett, Attorney at Law, “Military Biography of William A. Clark” January 26, 2000 p. 22

When he left Bill was accompanied by at least a few other 82nd troopers whom had been discharged in the same timeframe. At the port of Antwerp, they boarded their transport to the US, most likely a liberty ship, on November 1, 1945. Bill had with him a German Luger pistol which he had carried since he took it in Sicily from a German officer killed in the pill box battle of July 9/10 two years and four months before on that dark night of his first combat jump. He said rumor had it that once the ship docked in New York, MPs onboard were under orders to search paratrooper duffle bags, and confiscate any German firearms. Men found with German guns were to be charged and arrested. The rumor had enough scare in it that Bill said he and the other troopers he was travelling with threw their Lugers into the ocean before the ship docked. When they disembarked from the vessel to his extreme dismay he discovered that the rumor was false. No searches of any bags took place. The men were simply herded off the ship as quickly as possible.

The exact date of Bill’s arrival in New York City was 11 November, 1945 making the duration of his transatlantic voyage 11 days.

Bill’s brother Henry arrived back to the US exactly one month later on December 11, 1945. Like Bill, he too was discharged at Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania. Henry wrote in his book that it was a process taking three full days beginning on the morning of December 13 before ending in the late afternoon of the 15th. Source: Clark, H. “The War I Never Fought: ‘Memoirs of a Rear Rank Rudy’” 2001 p. 119.

Henry must have had virtually the same discharge experience as Bill did. Indeed, Bill’s separation is dated November 15, 1945 (see Photo 1 below) which assuming he arrived at Indiantown Gap on the morning of November 13 (as Henry did one month later), he would have been discharged three days later in the late afternoon on November 15.

Photo 1: Bill’s Identification Card for enlistment in the Army Reserve Corps Dated November 15, 1945. Approximately 24 hours after this card was issued, Bill arrived home. Source: Author’s Collection

In Henry’s case on December 16, the next morning after his discharge, he boarded a bus to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania where he caught a train to Richmond, Indiana. From there he hired a taxi arriving home at about 4:00 AM on December 17. Source: Clark, H. “The War I Never Fought: ‘Memoirs of a Rear Rank Rudy’” 2001 p. 119.

As we shall see shortly, the US Army had sent Bill on his way with at least equal efficiency. He rode on a train to Cincinnati, Ohio, as per his interview with Herd Bennett cited above, on the morning of November 16. Later that same day he caught a bus to Hamilton, Ohio where his aunt drove him home arriving that evening.

It is known that Bill arrived in the evening and that his mother and father stayed up for two days talking with him. For his parents to stay up for two days must have meant that he arrived on a Friday night. Bill’s father was employed full time as a machinist at the nearby Airtemp factory. He left for work at 5:00 AM and arrived home at 6:00 PM each evening. The only days of the week he could have spent 48 hours on anything outside of work was Saturday thru Sunday.

Therefore, Bill must have arrived home the evening of Friday, November 16, 1945, most likely after 6:00 PM.

Home at Last

The family was very surprised to see Bill the night he came home. He was spotted outside past the front living room window and no one could believe their eyes. They knew he was coming soon, but not when. Exactly one month and a few hours later, Henry arrived home. Everyone was so overjoyed to be together again.

Bill brought home a big green duffle bag almost bursting with all sorts of memorabilia. It was a treasure trove of German military attire, medals, books, silverware, coins, bank notes, knives etc. Over the ensuing years most of its contents have been lost, given away, or thrown out. Very little of it remains today.

Photo 2: Bill’s 82nd Airborne coat hangs from the door knob of the family farm barn. Left is an unknown tube shaped object. Front left is an 88 mm shell casing. The WWI helmet belonged to Bill’s father Henry Clark Sr. The duffle bag belonged to Bill. His name and serial number are visible. Circa 1978 Source: Author’s Collection

Photo 3: A 5 Reichsmark bank note, dated 1942. The Nazi emblem of an eagle clasping a swastika in its talons is still visible in the lower left. A Hitler youth is illustrated on the right. Perhaps already battered and torn when it came into Bill’s hands, this is one of the few artifacts from his duffle bag with the fortune to survive to the present day. Source: Author’s Collection

Photo 4: Reverse side of the 5 Reichsmark bank note apparently displays a church with a farm worker on the left and a carpenter on the right. Source: Author’s Collection

Photo 5: This 2 Rentenmark bank note dated 1937 has survived the ravages of time in quite good condition. The Rentenmark was issued to battle hyperinflation, rampant in Germany after WWI. The first issue of the currency occurred in 1923 and the last in 1937 – the date of this particular note. Source: Author’s Collection

Photo 6: Reverse side of the 2 Rentenmark bank note. Source: Author’s Collection

Photo 7: One of Bill’s 82nd Airborne “All American” AA shoulder patches. There are eight of them remaining. Most are heavily soiled like this one with ground in dirt. It was customary for paratroopers to remove their shoulder patches as a keepsake after a battle was over as soon as they received a new uniform. Source: Author’s Collection

Photo 8: Another of Bill’s 82nd Airborne shoulder patches. This one is perfectly clean. Source: Author’s Collection

Photo 9: The complete 82nd shoulder patche with the word “Airborne” positioned above the AA insignia, exactly as it appeared on Bill’s Ike jacket. Source: Author’s Collection

Photo 10: One of Bill’s original Parachutist patches worn on his garrison cap. It was replaced by the patch superimposing a glider over a parachute on one patch, much to the annoyance of the early qualified paratroopers who disapproved of the change. Source: Author’s Collection

Adjustment to Civilian Life

After Bill’s initial joy at returning home in one piece, the economic privations of the postwar period began to set in. The road to recovery looked like it was to be long and drawn out. For a time and to varying degrees the wartime rationing of food, shoes and gasoline continued. Living on the farm insured the Clark’s had plentiful food including chickens, milk, eggs, and vegetables. Fabric for home sewing was unavailable. Everything that could be was recycled and repurposed.

Bill’s brother Henry reflected on the lack of economic goods:

“I tried on one of my suits and it still fit. My brother [Bill] told me that I would be wearing the O.D.s (olive drab) for a while, he was right. Everything was in short supply for a while. Buying a car was out of the question, however my brother and I had bought a car before the war and it was still in fairly good shape. Gas now was no problem”. Source: Clark, H. “The War I Never Fought: WWII Memoirs of a ‘Rear Rank Rudy’”, 2000 p. 119.

Photo 11: At Right Bill’s father Henry Clark Sr.; left Bill’s youngest brother James Clark; Middle Bill’s older brother Henry Clark Jr., dressed in his Army Air Corps uniform, Circa December, 1945. Source: Author’s Collection

The brothers reluctantly wore their uniforms for a time. However, there was one item of military attire which Bill favored and that was his pair of paratrooper jump boots. They were of such good quality and so smart looking that he wore them for years until they finally succumbed to wear and tear. Until clothing eventually became more widely available, Bill used his sewing skills from his time as a parachute rigger to fashion several good shirts for himself out of the cotton sacks used to deliver chicken feed. Surprisingly, the cotton being of garment quality was quite smooth and the sacks large enough to make man sized shirts with seams in the right places. Source: Interview with Bill’s Sister Doris, 2006

Wage and price controls were still in effect in1949 and housing was unavailable because nothing was built during the war. Returning soldiers married quickly and were in desperate need of housing. They bought land and started building their homes by constructing the basement first. They covered it with a roof and lived in it until they were able to acquire more building materials which could take years and in some cases never happened. Source: Ibid.

Veterans had great difficulty finding jobs with the economy wide shift from war materiel to peacetime products and services and a large pool of skilled factory labor left over from the war years. Combat veterans, for the most part did not have the skills required of manufacturing, nor those of service industries.

One 505 PIR veteran wrote of these problems on recalling his exit interview from the Army at the Indiantown Gap Separation Center:

“The interviewing officer was supposed to write my military occupations on some form or other so my prospective employer would know my skills. ‘So, what did you do during the war?’ he asked. I explained that I had held positions of squad leader, platoon sergeant, and platoon leader in combat in the parachute infantry. ‘Yes, but what did you really do in the war?’ he replied.

I was getting a little upset. The guy was a captain and I was a second lieutenant. I said, ‘what do you mean? We fought the war.’ Then he said, ‘Yeah, but what skills did you learn?’ Now I was really agitated. ‘You don’t have to put anything on that form,’ I said, ‘because there’s not much need in civilian life for how to throw a grenade, push a bayonet into someone, shoot people, tear down a machine gun and reassemble it, or for combat leadership skills. I don’t know how to relate these things to civilian experience’. Source: Wurst S., & Wurst G. “Descending from the Clouds: A Memoir of Combat in the 505 Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division” 2004, p. 256.

Because of their lack of civilian job skills, and the trauma they continued to suffer, a number of veterans were unable to make the transition back to civilian society. Some became drifters and vagrants, while others only partially made the adjustment. These men paid one of the highest prices for surviving the war and even today the fates of a number of them are unknown.

Obviously Bill was traumatized by what he had endured. His suffering never went away. On top of that, he was torn between the excitement of a life of war and the more sedate life of a civilian. He had to unlearn all of the psychological coping mechanisms needed to embrace the horror and terror of armed conflict and relearn those needed for a life of peace. It was an arduous process which took years and was never fully completed. During the early period after his return he had been in contact with several other veterans from his unit. They wrote letters to one another once back in the States with the singular purpose of organizing themselves to re-enlist the Airborne. It is clear from these letters there were times when the temptation to permanently break away from civilian society proved almost too strong.

One letter from fellow 82nd PMC rigger, William Cody, is telling of their troubles:

September 12, 1946

Hi Stab, [Bill’s nickname given to him by the men in his Company]

How goes it. Got your letter last night when I went home from work. Yep, it’s true. I am working for a change. What a job. I don’t do a thing all day. But boy the walking I do is enough for six men. I bet I cover about 30 miles a day.

Now about that letter you didn’t get from me telling you to come on up [from Ohio to Massachusetts]. I wrote it but never did mail it. I found it a few days ago and burnt it. Now if you want to wait a month or more we will go back to the army then. Right now I have to work to get some cash…

In the mean time you can look for Pee Wee [fellow 505 PIR rigger Henry Lewis - an enormously respected and popular figure in the 82nd Airborne Division in WWII]. I sure would like to have him with us. How about it. If we had Pee Wee with us every thing would be fine. Then the “big 3” would be together once more. If you see him tell him I said to get on the ball an drop me a line telling me whether he is going with us or not. And he had better say he is…

Your Pal,

Bill (Eagle)

From the perspective of employment, Bill was one of the lucky veterans. He went to work at the Aetna Paper Company. The company had kept his job open for him during the war and even paid his Christmas bonus each year he was away. Bill stayed with the company until his retirement 40 years later.

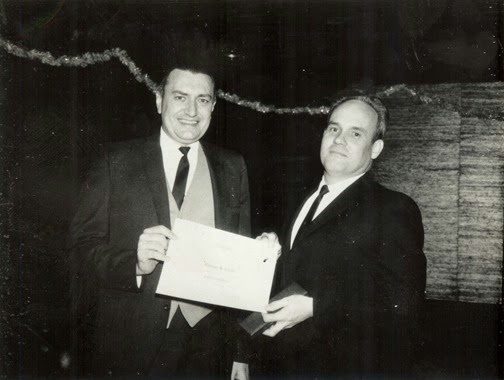

Photo 12: Bill on right receiving his award for 30 years of service as an employee at the St. Regis Paper Company (Previously the Aetna Paper Company and later the Howard Paper Company). Source: Author’s Collection

The company eventually went out of business and later succumbed to vandalism and arson. It was demolished in 2010. Follow this Flickr link for pictures of it before being torn down https://m.flickr.com/#/photos/49506449@N08/sets/72157624916054683/.

Photo 13: Bill’s certificate recognizing his 30 years of service to the company. He retired 10 years later after 40 years of employment. Source: Author’s Collection

Bill was active on the margins 0f the 82nd Airborne veteran’s society for a few years after his discharge, but that didn’t last long and neither did his desire to re-enlist in the Airborne. He decided to sever all ties with his former friends and the 82nd Airborne in general as part of his effort to move ahead with his life. In doing so he had the strong support of his parents and later the unwavering devotion of his wife, Isabel. Of particular note was his father and WWI veteran, in whom over the years he confided a great deal about the war. He also maintained a close relationship with his cousin Bill Rogers, a fellow WWII paratrooper, who had fought with the 101st Airborne Division from Normandy until the end of the war. Late in life, these two were known to visit one another often; regularly taking six mile walks together almost every evening. In these people, at different stages, Bill had the support network to make the adjustment back to civilian life. In himself, he found the courage needed to lead a solid postwar life. He successfully held down his job, married, and raised a family.

On at least two occasions Bill went back to tour many of the places he had been stationed including North Africa, Ireland, England, France, Netherlands, Belgium and even Germany.

Nevertheless, the war had left deep wounds in his psyche which lasted all of his life. A quote from his sister sums it up quite well:

“Another free time activity [of paratroopers] was sharpening their knives to a razor edge. He [Bill] described how to creep up on an enemy and kill him silently and how to break a bottle on a bar and use the neck for a weapon. When anyone pulled a knife on you if he aimed in the direction of stomach or heart with the sharp side of the blade pointing up he showed that he was an experienced knife fighter. Any other stance was not threatening and could be defended. This information was just what I needed to know to cultivate nightmares. One could easily be overcome with grief when you look at this young man whom you have known all your life and realize what he had to learn to survive, then reverse the process to live in civilian society. You have to respect the courage on both ends of that kind of life.” Source: Bill’s Sister Doris, 2005

In 2001 my father and I made a trip to see Bill in his Ohio rest home, and had the good fortune to gain a rare insight into Bill’s past through his “Ike jacket”. The jacket’s official designation was “Wool Field Jacket, M-1944”. Troops also referred to it as the ETO (European Theater of Operations) jacket, but it was more popular to call it by General Eisenhower’s nickname.

Whenever we would visit Bill, he always liked to take trips over to the farm house outside of Eaton Ohio, about 2 hours’ drive away. During this trip our plane arrived at Columbus Ohio airport at about 4:00 PM, giving us the evening to prepare before visiting Bill first thing the next morning. Dad took advantage of the time by driving out and checking on the farm house. One of the things he did was to position Bill’s Ike jacket, so that he would be sure to notice it as we walked through the house the next day.

On the morning of this visit, we got up early, had breakfast, picked up Bill and drove off towards Preble County from Bill’s rest home in Dayton, Ohio. As we made our way, Bill talked fondly of farming, tractors and life in Preble County. He got excited as we approached the farm.

When we got out of the car the first thing he wanted to do was to check in on the farm house. We entered through the back door opening into the kitchen. As we walked into the dining room, Bill saw his WWII Ike Jacket hanging on a chair next to the old dining table. A look of surprise came over his face accompanied by a warm smile as if he was unexpectedly reunited with an old friend. Bill hurried over to the jacket and affectionately caressed its coarse wool. His breathing began to quicken. His demeanor sharpened and the years appeared to drain away. It was as though he was once again the young man to whom the jacket belonged. The light in the dining room was diffuse and faint making his cool blue eyes reflect the deeper blue behind the 82nd Airborne’s AA insignia on the jacket’s shoulder patch. While he gazed upon his jacket I became transfixed and all at once it seemed that these were the only two colors in the dim room. With a faraway look in his eyes and in a distant voice he humbly murmured:

“Mmm… I guess I was useful to someone at one time or another”.

William Abner Clark October 5, 1922 - February 13, 2008

© Copyright Jeffrey Clark 2014 All Rights Reserved.

Good post.

ReplyDeleteWow! this is Amazing! I got free 10,000 instagram followers! Click here to get your free instagram followers!

ReplyDeletegeen

ReplyDelete