Attack on the Aid Station

As we know, Bill injured his knees in the Sicily jump. In his letter to Doris, dated June 13, 1945 he writes:

“First the men with 85 points go home the 25th of this month, I have 84 but still might make it a little later on. What’s left of the division after these men go will move to Berlin to do occupational duty and reform a new or almost new 82nd. Most all the old men have enough points to get out. There are only two of us in this company who came overseas with this outfit and don’t have enough points to be discharged. I really have 89 points but my service record is messed up. Received a “Purple Heart” in Sicily, which was recorded on a medical record. The First Aid Station received a direct hit from an 88m.m. shell shortly after I left it so the records were destroyed. I think I can still get it though, but it will take a long time. I thought it was on my service records, but recently found out it wasn’t.” Source: “Letter to his sister Doris Clark”, William Clark June 13, 1945 page 1

In an annotation to the letter Doris relates some more information about the aid station as told to her by Bill. She writes:

“He explained that he hurt his knee in the jump and later went to the Aid Station. They attended his knee and he was supposed to stay until he was released, but he had a strong feeling that he should get out of there and started to leave. A couple of orderlies tried to hold him, but he broke away and got up to the top of a nearby hill as quickly as he could and sat down to rest. As he watched there was a direct hit on the Aid Station and all of the occupants were killed.” Source: Doris (Clark) Orr, date unknown

On November 4, 2005, I interviewed Bill’s brother Henry Clark about the incident and he confirmed that Bill had told him the same thing as was documented in Doris’ annotation to the letter. In my last interview with Bill himself on March 22, 2006, I asked him if he knew where the aid station was. He tried to tell me. Unfortunately, despite all his efforts he was unable to form any words that would help in positioning the site in time or location.

Operation and Organization of Aid Stations at the time of the Sicily Invasion

To obtain a better contextual understanding of the aid station incident, it is useful to review the operational and organizational practices of the Army Medical Department at the time of Operation HUSKY and then compare them to Bill’s own recollections of the incident. These practices can be found in the:

Medical Field Manual: Mobile Units of the Medical Department (FM 8-5). published by the War Dept. on January 12, 1942.

Medical Field Manual: Medical Service of Field Units (FM 8-10) published by the War Dept. on March 28, 1942; and

Location of an Aid Station

The FM 8-10 manual describes the policy for locating a suitable position of an aid station:

“b. Location.- Because of the greater importance of other requirements the physical features of the site of an aid station will vary from a comfortable building to a few square yards of ground without shelter from the elements.

(1) Desirable features.- It will rarely be possible to find site that satisfies all requirements but the following features are desirable in an aid station site:

(a) Protection from direct enemy fire.

(b) Convenience to, troops served.

(c) Economy in litter carry,

(d) Accessibility to supporting medical troops.

(e) Proximity to natural lines of drift of wounded.

(f) Facility of future movement of the station to front or rear.

(g) Proximity to water.

(h) Protection from the elements.

(2) Undesirable features.- The following features are highly undesirable, and are to be avoided whenever possible.

(a) Exposure to direct enemy fire.

(b) Proximity to terrain features or military establishments that invite enemy fire or air action, such as prom marks, bridges, fords, important road intersections, positions of artillery and heavy weapons, ammunition and other Contributing points.

(c) Proximity to an exposed flank.” Source: “MEDICAL FIELD MANUAL - FM8-10 Medical Service of Field Units March 28, 1942” pp. 42 – 45 Retrieved on May 11, 2011 from http://www.90thidpg.us/Reference/Manuals/FM%208-10.pdf

(3) Type location.-The location of an aid station within wide limits, depending upon the situation. No definite rules can, or should, be laid down, but the following may be offered as a general statement of the type location aid station of an infantry battalion in the front centrally located site, from 3 to 800 yards in rear of the front line combining as few undesirable features with as many desirable features (listed above) as can be had in the terrain available.” Source: Ibid.

Figure 1: Illustration of an Aid Station Location

Source: “MEDICAL FIELD MANUAL - FM8-10 Medical Service of Field Units March 28, 1942” p. 44Retrieved on December 9, 2011 from http://www.90thidpg.us/Reference/Manuals/FM%208-10.pdf

Procedures and Organization of an Aid Station

The FM 8-10 manual goes on to explain the procedures and organization of an aid station:

“d. General procedures of operation.-

(1) The aid station of a unit is established only when movement of the unit is unsteady, very slow, or halted altogether (see (3) below).

(2) An aid station must keep at all times in contact with the unit it is supporting. It must be moved, by echelon if necessary, as soon as movement of the combat elements makes its location unsuitable.

(3) Only such part of an aid station is established as immediate circumstances require, or for which need can be foreseen. Rapid forward movement of combat elements is usually associated with small losses, and casualties can be collected by litter squads into small groups along the axis of advance and given first aid. Such casualties can be evacuated promptly by the medical unit in close support, thus relieving the need for an established aid station and permitting the medical section to keep up with the combat troops.

(4) An aid station is not the proper place for the initiation of elaborate treatment. Such measures will retard the flow of casualties to the rear and immobilize the station.

e. Organization.-

The organization of an aid station will depend upon the unit and the situation. In general, the functions of recording, examination, sorting, treatment, and disposition must be provided for in every situation. These will require one or more medical officers, assisted by non-commissioned officers and enlisted technicians. The allocation of personnel to these functions is a responsibility of the section commander.” Source: “MEDICAL FIELD MANUAL - FM8-10 Medical Service of Field Units March 28, 1942” pp. 42 – 45 Retrieved on May 11, 2011 from http://www.90thidpg.us/Reference/Manuals/FM%208-10.pdf

Types and Numbers of Personnel in an Aid Station

As is explained in the following excerpt from the FM 8-5 manual the aid stations themselves were comprised of a varying number of personnel:

“33. ORGANIZATION AND OPERATION OF AID STATION - The functions of an aid station are relatively constant, and the functional organization will depend largely upon the size of the aid station group among which the duties must be distributed.

a. Type functional organization. - As a type, the following functional organization of a battalion aid station is suggested. With the assignment of 5 medical and 3 surgical technicians as company aid men, and 12 unrated privates, first class, or privates as litter bearers, the following personnel remain for the aid station group: 2 officers, 1 staff sergeant, 1 Corporal, 1 unrated private, first class, or private, and 4 chauffeurs. In case the latter for any reason are not available, the bearer group is a possible source of station personnel. In any event, the following distribution of station duties is suggested:

(1) Officers (2).-(a) One commands section; battalion surgeon; in charge of aid station; first-aid treatment, sorting, and preparation of walking wounded for evacuation.

(b) One is general assistant to section commander; first-aid treatment and preparation of litter wounded for evacuation.

(2) Staff sergeant (1).- Section sergeant; general super-vision of all enlisted personnel; supply; assists the section commander in his technical functions.

(3) Corporal (1).-Assists the officer in charge of the litter wounded; in absence of trained technician, performs shock nursing, sterilizes instruments, and administers hypodermic medication.

(4) Private, first class, or private, unrated (1).-Casualty records.

(5) Chauffeurs (4).-Utilized when available for assistant in litter wounded department; assistant in walking wounded department; property exchange; drinking water; hot liquid nourishment for patients; shock nursing; sterilization of instruments; hypodermic medication.

b. Operations.-(1) Casualties from front line units normally arrive at an aid station by one of two ways, walking with or without assistance, or carried by the litter squads of the battalion section. In other units casualties May arrive via ambulance or other transport.” Source: “MEDICAL FIELD MANUAL – FM 8-5 Medical Field Manual: Mobile Units of the Medical Department March 28, 1942” pp. 41 - 42 Retrieved December 9, 2011, from http://www.90thidpg.us/Reference/Manuals/FM%208-5%201942.pdf

Figure 1 below shows how the medical operation during an invasion was organized and the place of the aid station in the process of treating and transporting wounded from a battle zone.

Figure 2: Layout of Medical Field Operations in the Mediterranean Theater

Source: “The Chain of Evacuation” AMMI - THE DEFINITIVE 20TH CENTURY MILITARY MEDICAL HISTORY SITE! Retrieved on May 11, 2011 from http://web.archive.bibalex.org/web/20060212063007/http://www.ww2medicine.org/chain.html

FM 8-5 describes what happened to a wounded soldier when he arrived at a battalion aid station:

“(2) The casualty is examined and necessary first-aid treatment given either to enable him to return at once to duty or to prepare him for further evacuation. Such treatment is limited to the arresting of hemorrhage, immobilization of fractures, sterilization of wounds (so far as practicable under the conditions), application of sterile dressings to prevent further infection, and the administration of sera and other necessary preventive or palliative medication. If possible, the patient is sheltered from the elements and given a hot drink to relieve exhaustion and prevent or control shock. The necessary entries are made on his EMT, and he is either turned over, at the aid station, to the medical unit in direct support or returned to his organization.” Source: FM8-5 - Medical Field Manual Mobile Units of the Medical Department January 12, 1942 page 42. Retrieved on May 11, 2011 from http://www.90thidpg.us/Reference/Manuals/FM%208-5%201942.pdf

Note: an EMT is an Emergency Medical Tag.

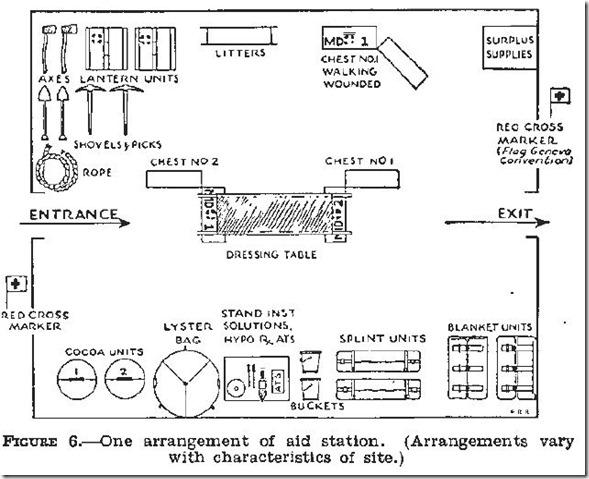

Examples of how an aid station was organized are shown in Figures 2 and 3 below:

Figure 3: Example Layout of Aid Station

Source: “MEDICAL FIELD MANUAL - FM8-10 Medical Service of Field Units March 28, 1942” p. 43. Retrieved on December 9, 2011 from http://www.90thidpg.us/Reference/Manuals/FM%208-10.pdf

Figure 4: Another perspective of an Aid Station Layout

Source: “MEDICAL FIELD MANUAL – FM 8-5 Medical Field Manual: Mobile Units of the Medical Department March 28, 1942” p. 40. Retrieved December 9, 2011, from http://www.90thidpg.us/Reference/Manuals/FM%208-5%201942.pdf

Observations and Deductions

From this information some important observations can be made. First, it was possible for an aid station to be very close to the front lines, anywhere between 3 and 800 yards, certainly close enough to be shelled by enemy artillery including 88mm canon fire.

Second, wherever possible, aid stations would set fractures, sterilize wounds, change dressings, and treat victims of shock and exhaustion by retaining soldiers inside the boundary of the aid station and providing them with hot drinks. Aid stations were composed of several personnel including doctors, orderlies, nurses etc. The numbers and compositions of these personnel would vary depending on battle field events.

Doris Orr states in her foot note to Bill’s letter that orderlies from the aid station tried to restrain him after his knee was treated and that Bill broke away from them and climbed a nearby hill to rest. Perhaps the aid station doctor or an orderly thought he was suffering from exhaustion or shock and requested that he stay at the aid station, sip a hot drink and recover his strength. The fact that Bill climbed a nearby hill and sat down to rest would support the assertion that Bill needed to rest.

Third, the aid station was probably stable and established, not moving forward quickly, possibly indicating a situation where the combat troops in front of the aid station were making slow headway or were dug-in in a defensive posture such as during an enemy counter attack, or while awaiting reinforcements. Doris’ foot note states that orderlies were present and his wound was treated. Bill’s letter mentions that a medical record was kept. Therefore the aid station was large enough to have a doctor or medic present to treat his injury and probably orderlies to record information on causalities and treat shock victims. This would support the case that the aid station was in a stable location.

Fourth, aid stations kept records of the wounded besides the Emergency Medical Tag (EMT). The EMT is physically attached to the wounded soldier. It contains the soldier’s name, unit, description of wound and treatment administered. The EMT remains with the patient until he is ready for duty or reaches a fixed hospital. Aid station personnel also kept records about specific casualties that passed through the aid station. Source: “WWII MEDICAL DETACHMENT attached to Infantry Regiment” Alain Batens March 19th 2002 Retrieved May 11, 2011 from http://www.mtaofnj.org/content/WWII%20Combat%20Medic%20-%20Dave%20Steinert/WWIIMedicalDetachment.htm

It was necessary to keep information other than the EMT because some soldiers would be treated and sent back to their unit to continue duty. In these cases the aid station was the only point of contact that a medical detachment had with a soldier and therefore the only source that could verify that a particular soldier sought medical attention. Furthermore, personnel in aid stations had been known to recommend Purple Heart awards to soldiers, as in the case when Col. Gavin visited an aid station after the battle of Biazza Ridge to receive treatment for shrapnel wounds. The personnel at that aid station said they would put Gavin down for a Purple Heart award. Source: “Onto Berlin” Gavin, 1978, pp. 42-43.

As Bill said in his letter to Doris, he received a Purple Heart in Sicily, which he said was recorded on a medical record. Figure 5 below is a copy of a Company Morning Report for Service Company 505th PIR from Sicily dated July 21, 1943. It contains information originally recorded on a medical report at an Aid Station on July 14, 1943. I am told these Morning Reports should indicate if a Purple Heart was recommended. Even if the record of Bill’s Purple Heart recommendation wasn’t destroyed, Figure 5 demonstrates how much information is often incomplete regarding injured personnel. In the first entry for Ernest Seitz the hospital he was treated at is listed as unknown. In the case of the second entry, James Nelson it states: “Information not available as to the extent of injuries and whether or not hospitalized or evacuated.”

Image Source: National Archives

There are two possibilities given Bill’s recollections, US Army medical practice, and his likely location during the invasion that would explain the aid station incident:

- An aid station belonging to a medical unit attached or organic to the 45th Infantry Division at 2:40 hours on July 10;

- The clearing station set up by the 307th Medical Company, organic to the 505th PIR or another nearby aid station on July 11.

Let’s now explore each of these possibilities.

Possibility 1: A 45th Division Medical Unit

At the location and time of Bill’s jump, there were no aid stations. He landed in hostile territory, behind enemy lines. As explained above, aid stations were set up between 3 and 800 meters behind front lines. Some of the troopers in Bill’s serial did link up with units of the 45th Division, one example being Col. Gavin’s group that linked up with the 45th at 2:40hours. Source: “82nd Airborne Division in Sicily and Italy” page 22.

The CENT force of the invasion was comprised of units of the 45th division. These forces landed on the beaches east of the town of Scoglitti (See Map 2:View The German Counter Offensive July 10 - 11th). Medical units of the CENT force included the 120th Medical Battalion organic to the 45th, the 54th Medical Battalion; a platoon of the 11th Field Hospital; and seven teams of the 3rd Auxiliary Surgical Group. Each medical unit went ashore with their assigned combat units. Within the first two hours of the landings, battalion aid stations were set up between one half and one miles inland Source: “Medical Department: Medical Service in the Mediterranean and Minor Theater”, Wiltse C., 1967, pages 152 -153

After his jump, Bill could have visited an aid station set up by the 120th Medical Battalion. Since the 120th Med. was organic to the 45th Division it’s likely that they would have been in the same general location and at the same time as the groups of paratroopers that linked up with the 45th Division. The 120th Med. set up aid stations behind the 45th front lines. Doris Orr states in her footnote that Bill visited an aid station after he landed. Bill’s first opportunity to do so would have been the aid stations supporting the 45th and would have been the 120th Med.

The 45th was under fire for several hours during and after the landings. Due to enemy resistance, it wasn’t until 4:00pm on July 10 that the 120th Med. was able to set up a clearing station some three miles inland. Source: Ibid

Given this, it is possible that Bill visited an aid station of the 120th Med. early on the morning of July 10 at around 2:30am – 3:00am. The 45th Division was being shelled by enemy artillery at this time and was unable to make head way until several hours later. These were the conditions during which aid stations were typically set up with multiple types of personnel including doctors, nurses as well as orderlies who were charged with documenting medical records.

During the invasion, the policy was to set up aid stations close to the front lines. Bill came from a location behind enemy lines. The nearest aid station to him run by the 120th Med. would naturally be one that was close to the front lines. The terrain around the front lines at this time was hilly, which would allow Bill to climb a hill after he left the aid station.

At this point, I have been unable to find a report of an aid station that was hit by a shell killing its occupants and destroying the records. I am in the process of asking the Medical Dept of the Army for information that corroborates Bill’s recollections. Despite this, all of the policies and practices of medical units at the time of HUSKY do corroborate all of Bill’s recollections as recorded in his letter to Doris Orr and Doris’ footnotes to his letter. Therefore, I believe that this is the most likely location and time of the aid station shelling.

Possibility 2: The 307th Medical Company

The first medical clearing station to be established by the 505 was on Biazza Ridge on July 11. The 307 Medical Company set it up while under fire, so that the wounded could be given triage before evacuation to the coast. The clearing station was constantly under fire during the battle from German artillery, tanks, and small arms. Over the course of the day there were many wounded coming in to the clearing station, and it’s doubtful that Bill would have had his knee examined when so many seriously injured men needed attention. The clearing station was in a field behind the lines. In his letter, Bill states that his medical record was destroyed when a First Aid Station was hit by an 88mm shell. It is possible that this clearing station may have been maintaining medical records, including recommendations for awards of Purple Hearts. However, nothing is recorded about an 88mm shell hitting the 307 clearing station and the after action reports make no mention of any personnel at the clearing station being killed. The clearing station was behind Biazza Ridge. Biazza Ridge could look like a hill. It’s unlikely that Bill would have climbed it during the battle in order to rest, as it was itself under heavy fire from the Germans. In this immediate area Biazza Ridge is the only nearby hill so it is unlikely that Bill had his knee treated at Biazza Ridge.

There were other medical stations including aid stations in the Vittoria area. Perhaps Bill visited one of these other aid stations on his way to the battle at Biazza Ridge or sometime during the day of July 11 and an 88mm shell hit it.

One was set up in a house near the ridge where the Vittoria – Gela road crossed the railroad. It served as the living quarters for the Sicilian man who operated the boom gate at the railway crossing. On July 11, a medical team had set up an aid station in the building to perform emergency operations. Thinking it was the paratrooper’s command post; it was strafed and bombed by Luftwaffe ME 109 fighters. In fact, Col. Gavin had set up his command post in a mere slit trench on Biazza Ridge. The medical team had to vacate the structure and subsequently relocated to a farm house one quarter miles away Source: “Drop Zone Sicily”, Breurer, 1983, P. 140.

Bill’s Purple Heart

Initially, Bill wasn’t too worried about not receiving the Purple Heart, a fact that Henry Clark attested to during an interview on November 4, 2005.

Doris Orr also corroborates this:

“I doubt if he tried very hard to correct the record because I have heard that according to the Paratrooper code they thought that it was wimpy to get the purple heart.” Source: Doris (Clark) Orr 24 June 2005 page 7

Col. Gavin himself confirmed this sentiment. After the battle of Biazza Ridge he explained that the Purple Heart was shunned among members of the 505:

“My trouser leg was slightly torn, and my shinbone was red, swollen, and cut a bit. I must have been nipped by a mortar fragment the day before. I went to the nearest aid station; they put on some sulfa power and I was as good as new. They said they would put me in for a Purple Heart. I said nothing about it – I had already learned that among twenty-four hour veterans only goof-offs got Purple Hearts.” Source: “Onto Berlin” Gavin, 1978, pp. 42-43.

While Bill didn’t want the award at the time, later on in the war he was strongly motivated to get his Purple Heart instated as he indicated in his letter to his sister. A Purple Heart contributed five points towards the number needed to be discharged. Without it at the end of the war he was just one point short of earning the magic number of 85 points needed to avoid being assigned to dangerous occupational duty in post war Berlin.

One of the main reasons behind the 505 troopers’ attitude toward the Purple Heart was they felt it was given out too liberally. Col. Gavin’s case is a good example. In his own opinion his minor injuries didn’t warrant the award. At the time, the ease with which the Purple Heart was awarded devalued the US armed forces most important medal. Being killed or wounded is the greatest sacrifice a soldier can make. Those who receive the Purple Heart should be duly honored and respected.

© Copyright Jeffrey Clark 2011 All Rights Reserved.