In the second post on Normandy I had put forth the possibility of Bill being chosen for a mission to recover mis-dropped parachutes and equipment from the flooded fields of the drop zones as a potential reason for his proven presence in Normandy during the time and geographic limits of that combat zone as stipulated in GO 33 WD 45 .

While researching Bill’s involvement in the Normandy campaign, I found evidence that conflicted with that possibility. This evidence details Bill’s involvement in an ‘off the books’ mission – one that was possibly not documented – in which he parachuted into the ‘bocage’ or hedgerow country of Normandy three days before the invasion. At first I dismissed it out of hand but later became intrigued by the possibility. So I decided to research it further and, to my surprise, found plausible evidence to lend it credibility, including:

- Documented French eye witness accounts of American paratroopers in Normandy on June 3, 1944

- Testimony and documented evidence of other US special operations, including American paratroopers, in Normandy on or before June 3, 1944

- Calls for volunteers for “other special missions” into Normandy made by 82nd Airborne commander General Gavin

What this amounts to is a third plausible explanation for Bill’s proven presence in Normandy. Incidentally, it is the explanation I have the most confidence in as it is the one which best fits the facts surrounding Bill’s involvement in that campaign.

Nightmares

After his Army discharge at Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania on November 15 1945, Bill made his way home to the Clark family farm in Preble County, Ohio, to a jubilant welcome from family and friends. He was overjoyed to be home. His parents and family were euphoric that he had made it back in one piece. The long years of worry and uncertainty were over. Years of waiting through the streams of news reports detailing Bill’s outfit in peril; the false letters unequivocally announcing his death in Sicily; and the delay in his discharge because of the mix-up on the points in his service record following the Sicily jump.

On that cold November night of his homecoming, he and the family gathered around the warm potbelly stove in the living room, and Bill began to tell them his stories – the humorous and horrific; the sorrowful and exultant. He recounted his adventures in North Africa, the invasion of Sicily and his grief when his friend died at Biazzo Ridge. They laughed about his good times in English pubs and the bad English beer. They listened intently as he described Montgomery’s folly by invading Holland, the bedlam as he scrambled to get to his unit at the Battle of the Bulge and were shocked to hear about the horror he found in liberating Wöbbelin Concentration Camp near Cologne, Germany. After all of these battles and experiences, they were amazed that he had survived fighting the Russians and the remnants of the post-war Nazi resistance movement which he called the Werewolves, in Berlin. They stayed awake for two days and nights hanging on his every word, marveling at how he had cheated death so many times, and pinching themselves back into the reality of his presence.

They were curious, however, about his apparent reluctance to talk about the details of his jump during the invasion of Normandy. In their view, his role in the early part of the largest combined air and seaborne invasion ever attempted needed more explanation. When they asked questions about it, he gave vague details about the jump and picked up with the battle to gain control of Sainte-Mère-Église and the difficulty in breaking through the hedgerows. Ecstatic to have him back, they didn’t push him. There would be plenty of time for explanations later.

But later never came. When asked, he wouldn’t talk about it. He would simply clam up. After the excitement of his return home worn off, Bill began making the arduous adjustment back into civilian life. He unlearned the survival skills, associated behavior patterns, thought processes, and habits required of a soldier and relearned those needed for life in a free society.

It was during this time of adjustment that the nightmares began. Bill’s sister explains:

“Bill had terrible nightmares after the war. He would wake up screaming. Daddy would sit at the edge of Bill’s bed and wake him and talk to him until he was calm. They talked about what was causing the nightmares.” Source: Doris Orr phone interview with author March 18, 2009

Bill’s youngest brother, James Clark, lived at home during the time and remembers the story of Bill in Normandy as told to him by his mother.

“During one of these talks with Daddy, Mother said that Bill told him of an incident that happened in Normandy. She said that while waking up from a nightmare, he told Daddy that he jumped into Normandy three days before D-Day. He was only able to move at night and during the day he took cover. They worked in teams of two. The mission’s objective was to locate, and later at a predetermined time, cut communication cables and otherwise disrupt communications.” Source: James Clark, phone interview with author March 15, 2009

By themselves these family recollections give the appearance of a story passed from Bill, to his father, to his mother, and then to her children and grand children. Admittedly, it is third hand and like the game of Chinese whispers, the details could have possibly changed. To lend the story credibility corroborating and plausible testimony is needed. As the fates would have it, just such evidence exists in a variety of surprisingly diverse forms.

The French Resistance in Normandy

There is an account of the French Resistance in WWII entitled “La Manche mouvements de résistance” or “The Movements of the Resistance in the Channel”. The document can be found on this web page http://beaucoudray.free.fr/1940.htm. It is a meticulously detailed chronological account of the people in the French Resistance in the “Manche” (Channel) Department and in the canton of Beaucoudray between June 1940 and July 1944.

The work is a compilation sourced from the archives of famed French Resistance fighter André Debon. After the war, he became recognized as a foremost historian on the Resistance in the Channel Department. Source: “Résistance, Maquis et Libération du département de la Manche” 2009 Retrieved from http://www.ww2-derniersecret.com/B-Normandie/50.html

He published two books on the subject entitled:

- “La Résistance dans le Bocage Normand” (In English: Resistance in the Normandy Bocage) by André Debon & Louis Pinson (1994)

- “La mission Helmsman. Une contribution décisive de la Résistance au succès de l'opération Overlord (juin-juillet 1944)” (In English: The Helmsman mission. A decisive contribution by the Resistance in the success of Operation Overlord (June-July 1944) by André Debon (1997)

Debon had been a member of the French Resistance since 1940 and, after years of involvement in various networks he joined the National Front resistance network in the “Manche” (Channel). Among his notable achievements were clandestine printing of anti-Nazi propaganda and his pivotal role in the Hellmsman mission which penetrated the German lines in the Bocage (hedgerows of Normandy) to successfully report on the German defenses leading to accurate planning for Operation Cobra. Source: “Résistant de la Manche” Retrieved from http://www.wikimanche.fr/André_Debon

A native and fluent French speaker translated into English the relevant parts of the “La Manche mouvements de résistance” document, which appear in the section entitled “L'AIDE AUX PARACHUTISTES AMÉRICAINS” or “AID TO AMERICAN PARACHUTISTS”. There are three paragraphs relating to American parachutists landing in Normandy before the main airborne invasion force:

Paragraph 1 Original French “L'AIDE AUX PARACHUTISTES AMÉRICAINS” Trois jours avant le débarquement du 6 juin, quelques parachutistes isolés sont largués dans le nord-est du Cotentin, vraisemblablement dans le but de préparer les opérations. Ainsi, le 3 juin, un lieutenant aviateur américain tombe sur la commune d'Appeville, à l'extrémité ouest des marais du Cotentin. Il est aussitôt camouflé dans une étable, au village de la Picotière et interrogé, Madame LANGLOIS et l'instituteur LECLER servant d'interprètes. Il déclare devoir se rendre à Houesville, sur la rive opposée où il doit rejoindre un autre aviateur, à la ferme CHUQUET. Dès le lendemain, malgré la tempête qui soulève l'eau des marais, Henri de SMEDT prend en charge l'aviateur et le mène sur son bateau plat, traversant au mépris du danger la large étendue d'eau qui sépare les deux rives. English Translation “AID TO AMERICAN PARACHUTISTS” Three days before the June 6 disembarkation, a few scattered paratroopers were dropped on the northeast side of the Cotentin peninsula, with the goal of preparing for the upcoming invasion. As part of this operation, on June 3, an American paratrooper parachutes into the town of Appeville, located on the western marshes of the Cotentin peninsula. He is immediately hidden in a stable in the village of la Picotière and questioned. Mrs. LANGLOIS and teacher LECLER served as the interpreters. He informed them he needed to go Houesville, on the opposite shore where he must rejoin another paratrooper at the CHUQUET farm. The first thing the next morning, despite the storm that raised the level of water in the marshes, Henri de SMEDT took charge of the airman and ferried him on his flat boat to the other shore in spite of the dangerous amount of water separating the two shores. |

Paragraph 2 Original French Dans la nuit du 4 au 5 juin, au Vast, dans la région boisée du Nord-Est du Cotentin, Jean POULAIN découvre 5 parachutistes. D'autres, revêtus de bleus de travail comme des ouvriers mécaniciens, se présentent chez Charles BLED. Ils sont munis d'un appareil de radio. Ravitaillés par les deux français, ils sont hébergés 4 jours dans une grange. Louis HOUYVET et d'autres recherchent de nuit des parachutistes. English Translation During the nights of June 4 and June 5, in the wooded region of Vast in the northeast of the Cotentin peninsula, John POULAIN discovered 5 parachutists. Others, clothed in workmen uniforms as mechanics, present themselves to Charles BLED. They carried a radio with them. The two Frenchmen provided food and housed the parachutists in a barn for 4 days. During the nights, Louis HOUYVET and others went in search of parachutists. |

Paragraph 3 Original French

Dans la soirée du 5 juin, à Neuville-au-Plain, l'institutrice Francoise AVENEL et sa mère aperçoivent, assis sur le rebord d'un talus, un parachutiste américain légèrement blessé. L'aviateur annonce l'invasion, cette nuit même, de milliers de parachutistes dans la région. Pendant que deux personnes figées font le guet, Mlle AVENEL fait entrer chez elle le blessé, soigne sa légère entorse, et l'aide à déterminer sur sa carte les lieux qu'il a mission de rejoindre. Arrive un jeune étudiant réfractaire au S.T.O., accompagnant un groupe de soldats alliés : il demande à Mlle AVENEL de servir d'interprète. Un officier présente une carte il veut atteindre le village de La Fière, près de la voie ferrée, et connaître l'importance numérique des ennemis dans la région. Il demande un guide, le jeune étudiant accepte cette dangereuse mission.Dans la même région, à 23 heures 30, Camille DUCHEMIN, de Fresville guide trois parachutistes venus se présenter chez son père, à la ferme du Bisson, jusqu'au village de Houlbey. Il leur indique la direction de Ste-Mère-Eglise, à 3 km de là.

English Translation During the evening of June 5, at Neuville-au-Plain, the teacher, Francoise AVENEL and her mother noticed seated on the edge of a slope, a slightly wounded American paratrooper. The aviator informed them of the invasion, that very night, of thousands of paratroopers in the area. While two people served as lookouts, Miss AVENEL took the paratrooper into her house and attended to his wound. She helped determine on his chart the location for his mission objective. Then, a young refractory student at the S.T.O. arrived accompanying a group of Allied soldiers: He asked Miss AVENEL to serve as an interpreter. An officer presented a chart. He wanted to get to the village of La Fière, close to the railway, and to know the total number of enemy in the area. He asked for a guide; the young student accepted this dangerous mission. In the same area, at 11:30 PM, Camille DUCHEMIN of Fresville guided three paratroopers, who had made themselves known to her father at the farm du Bisson, until they reached the village of Houlbey. She pointed them in the direction of Ste-Mère-Eglise, 3 km from there. |

Map 1: The Places named in the French Resistance Document – Section Aid to American Paratroopers

Note: Click on the Blue place markers for the names

Intriguing Consistencies from Completely Disparate Sources

Of the three paragraphs, Paragraphs 1 and 3 are the most interesting. Paragraph 1 states that an American parachutist landed in Appeville on the evening of June 3, three days before the June 6 D-Day. Furthermore, the account states that he needs to meet up with another paratrooper across the flooded countryside. This account shares a strong similarity to the story Bill told his father. Bill said he jumped into Normandy three days before the invasion, and he said he worked in teams of two. As we shall see, there are other reports by veterans, their families, their comrades-in-arms, and researchers who report occurrences of special missions into Normandy three days or more prior to the early morning of June 6, 1944, when the first pathfinders and subsequent paratroopers made their jumps.

Further Evidence of “off the books” Special Missions on or Before June 3, 1944

Several reports from veterans or their families exist which tell of special missions, involving parachuting into Normandy on June 3, 1944, three or more days ahead of the main invasion on June 6, 1944.

George Hjorth Combat Photographer Parachuted into Normandy 0n June 3, 1944 to Photograph the Invasion

In 1988, George Hjorth (pronounced Yorth) came forward with his story that he was parachuted into Normandy three nights before D-Day, on June 3, 1944 and was secreted away by the French Resistance. In the night before the June 6 landings, Hjorth was then escorted to an area above Omaha beach. Hjorth’s mission was to photograph the Allied landings on the beach. He had orders from his superior John Ford, head of the photographic unit of the OSS to photograph what he saw. According to Hjorth, what he saw was 300 - 400 American soldiers die in one and half hours of photographing. After Pearl Harbor, Hjorth had volunteered for service and had been selected as a member of John Ford’s photographic and film team. As a combat photographer, Hjorth captured images of several operations in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, France and Germany. After the Italian campaign he attended an airborne parachute training school and had been subsequently parachuted behind enemy lines nine times. He had been told never to reveal his missions or that he had parachuted into France three days before D-Day. Hjorth only came forth with his story when he heard that researchers were trying to locate the pictures he shot. Source 1: “John Ford: The Man and His Films” Tag Gallagher, 1988 p.256 - 274; Source 2: “Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford” Eyman. S, 1999 pp. 275; Source 3: Putting D-Day in Focus: Photographer Sheds Light on Mission Behind Nazi Lines” by Reza H. G., Los Angles Times, October 22, 1988 retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/1998/oct/22/local/me-35058 Source 4: “New View Of World War II: Museum To Get Long-Overlooked Color Films By Clendenning, A. Seattle Times, October 12, 1988 retrieved from http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19981012&slug=2777217

Professor Douglas Brinkley, an historian, was at the time the director of the University of New Orleans’ Eisenhower Center. Brinkley was the one foremost researchers on this topic. I am unaware of whether the photographic film was ever found. Recovery of the film was important according to Professor Brinkley as “…[it] shows how [Gen. Dwight D.] Eisenhower and the OSS saw the important need to capture on film what they knew would be the greatest invasion ever”. Source 3: Putting D-Day in Focus: Photographer Sheds Light on Mission Behind Nazi Lines” by Reza H. G., Los Angles Times, October 22, 1988 retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/1998/oct/22/local/me-35058

Edward Polasky PFC H Company 508th PIR Jumped into Normandy on June 3, 1944 on a Special Mission

An account reported in the Shelbyville Times-Gazette newspaper of Shelbyville, Tennessee is that of Edward Polasky, a PFC paratrooper in Company H of the 508th PIR. He died in Normandy on July 3, 1944. He is listed in the 508th PIR Honor Roll. Edward’s brother, Chester Polasky, researched his brother’s role in the war by attending reunions of Edward’s fellow 508th PIR paratroopers. During this period of research, Chester met a man that had served in the same unit as Edward. Using that connection, in 1980, Chester attended a reunion of the men from Edward’s unit. They knew Edward and fought with him in Normandy and told Chester the details of his brother’s jump into Normandy on June 3, 1944 on a special operation which took place, three days before the Normandy invasion. Source: “Visit to World War II casualty's grave kindles emotions for surviving family” Wednesday, November 11, 2009 By Mary Reeves retrieved from http://www.t-g.com/story/1586132.html

Joseph R. Beyrle 506th PIR, 101st Airborne Division Jumped Twice into Normandy in April and May 1944 to Deliver Gold Coins to the French Resistance

Joseph Beyrle’s missions are well documented. After arriving in England he trained with his unit, the 3rd battalion of the 506th PIR. In January, 1944, he was chosen to attend British Jump School which included three jumps from a balloon and two from an aircraft. After his training was finished Beyrle volunteered for a mission in April to parachute gold coins into Normandy and deliver them to the French Resistance. Two other men were chosen for the mission. They were taken to an airfield at Middle Wallop to be briefed and further trained before moving to another airfield to the North of Bournemouth. The men were issued with waist belts containing gold coins. They jumped after dark and were located by the French Resistance to whom they delivered the gold. They moved for several hours to an airstrip where a plane arrived at night and returned them to England. The mission was repeated in early May. Source 1: “History of Joseph R. Beyrle Wartime Service September 17, 1942 – November 28, 1945” Beyrle, J., updated April 21, 2013 Retrieved from “The 506th Airborne Infantry Assault Regiment” http://www.506infantry.org/stories/beyrle_his.htm. Source 2: “WWII hero ‘Jumpin’ Joe’ dies Joseph Beyrle’s improbable actions were honored by two nations” by Mendenhall, P., MSMBC Nightly News, December 13, 2004 retrieved from http://www.nbcnews.com/id/6708873#.UavkopzNld0 Source 3: “Paratrooper Joe Beyrle Dies; Fought for U.S., USSR” By Holley, J., Washington Post December 15, 2004 retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A240-2004Dec14.html

Alfred (Al) Tanz Jumped into Normandy on June 3, 1944 to Cut Electrical Wires behind the Invasion Beaches

Al Tanz served in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion (ALB) in the Spanish Civil War of 1936 - 1939 and had previously joined the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) in 1935. At the request of OSS chief Bill Donovan, in 1941 Milton Wolff, the last commander of the ALB and head of its veterans’ organization, was tasked with recommending ALB men as possible OSS agents. Donovan wanted men who would be able to work well with Communists in German occupied European countries. Many of these countries had influential Communist political groups. After the Germans attacked the USSR in 1941, these groups joined forces with pre-existing anti-Nazi resistance fighters or formed their own Communist resistance organizations. Essentially, Donovan thought that the ALB veterans which had supported the leftist Republican faction against the Nazi backed Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War would be trusted by the anti-Nazi Communists in these resistance groups. Milton Wolff (who later joined the OSS himself), first had to ask for permission from the CPUSA to recommend ALB veterans for service with the OSS. With the CPUSA’s blessing, several ABL veterans, including Al Tanz, were recommended to Donovan and later became OSS agents. In Tanz’ case, “…the OSS sent him to Great Britain, and he was among the OSS troops dropped into France in preparation for the 1944 Normandy invasion.” Source: “Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America” Haynes, J & Vassiliev, A. 2009 pp. 295 - 296

Richard Bermack gives more details on Al Tanz’ role in his Normandy jump in his book entitled “The Front Lines Of Social Change: Veterans Of The Abraham Lincoln Brigade”:

“Approximately four hundred and twenty-five Spanish civil war vets served in the U.S. armed forces during World War II…Some including Irving Hoff, Milt Felsen, Milt Wolff, and Al Tanz, worked with the OSS. Tanz was part of an elite group that parachuted into France in Preparation for the D-Day invasion of Normandy. His mission was to cut electrical wires overlooking the beach where Allied forces were to land. Later he participated in the liberation of Sainte-Mere-Eglise, the first village liberated on D-Day, June 6, 1944.” Source: “The Front Lines Of Social Change: Veterans Of The Abraham Lincoln Brigade” Bermack, R., 2005, unpaginated.

Existence of 82nd Airborne Men on “Special Missions” in Normandy

It is well known that pathfinder teams preceded the main body of paratroopers with the aim of setting up radar and light based signals to enable the C-47 pilots to navigate to their correct drop zone and deliver their cargo of men and supplies on target.

In fact, there were at least two opportunities for Bill to volunteer for the pathfinders. His first opportunity was for the canceled Volturno Rome jump when volunteers were asked to join the then experimental pathfinder initiative. Subsequently, the chosen volunteers jumped into Salerno.

The second opportunity was in England, shortly after the their arrival in early February, when again the men of the 82nd Airborne were asked to volunteer for a special mission. No details were included concerning the mission’s objective. Source: “Four Stars of Valor: The Combat history of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2006 p. 121.

Similar calls for volunteers were put out to the 507th and 508th PIRs. Subsequently, the 505th, 507th, and 508th PIRs each sent six officers and 54 enlisted men to the North Witham training center for the 9th Troop Carrier Pathfinder Group (Provisional). Source: “American Airborne Pathfinders in World War II, Moran, J., 2003, p. 33.

Indeed, as we shall see below, there is evidence that the well documented pathfinder missions were not the only secret missions involving 82nd Airborne personnel (and others) planned and executed prior to the main parachute drops on the night of June 5/6, 1944.

A Call for Volunteers for Pathfinders and “Other Special Missions”

In the planning for the airborne component of the Normandy invasion, there had been some disagreement about the composition of the three parachute infantry regiments making up the 82nd Airborne Division. General Gavin had advocated for the inclusion of the 504th PIR in the Normandy invasion. He was backed by commander of the 504, Colonel Ruben Tucker, who was “…eager to participate in NEPTUNE”. Source: “Ridgway's Paratroopers: The American Airborne in World War II” Blair C., 1985 p. 204.

But General Ridgway disagreed. He said the 504 was “so badly battered, so riddled with casualties…they could not be made ready for combat in time to jump with us.” Source: “Soldier: The Memoirs of Matthew B. Ridgway” Ridgway M., 1956 p. 92

This was a sentiment shared by some men of the 505 and many but not all of the 504. In a letter sent to Clay Blair for his book “Ridgway’s paratroopers: The American Airborne in World War II”, Allen Langdon, author of “Ready: A World War II History of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment” stated:

“I agree with Ridgway that the 504 was in no condition to go into Normandy. I was on the detail that readied their camp near Leicester and I saw them when they arrived. I have never seen a more beat-up bunch of men.” Source: “Ridgway's Paratroopers: The American Airborne in World War II” Blair C., 1985 p. 205.

In fact, 504th PIR men were represented in the Normandy campaign. Gavin approached the 504 asking “…for ‘volunteers’ [to be security men] from the regiment [504th] for the pathfinder teams and other special missions. Some fifty men stepped forward, twenty-six (two officers and twenty-four enlisted men) of them were dispersed into the teams from the 507th and 508th.” Source: American Airborne Pathfinders in World War II, Moran, J., 2003, p. 34.

Clay Blair wrote that:

“When Gavin sought ‘volunteers’ for the pathfinder groups and other special missions, perhaps fifty 504 men stepped forward. Among them were four officers. One was Tucker’s exec, Chuck Billingslea. Another was Ridgway’s protégé Hank Adams, who relieved Mel Blitch as commander of Tucker’s 2nd Battalion in Anzio. (Adams was attached to the 82nd’s G-3 section [Operations, Plans and Training Staff at Corps and Division].) Another was Willard E. Harrison, highly recommended by Tucker for his courage and resourcefulness. (Harrison became a sort of field assistant to Gavin.) In addition, Ridgway’s artillery commander, the burly Andy March, drafted Robert H. Neptune, exec of Griffith’s 376the Parachute Artillery, to serve as exec of d’Allessio’s hastily organized, mostly green 456th Parachute Artillery.” Source: “Ridgway's Paratroopers: The American Airborne in World War II” Blair C., 1985 p. 205.

The interesting fact mentioned in these quotations is that in addition to security men for pathfinder teams, Gavin was asking for volunteers for “other special missions”.

From the call for volunteers for the special mission, some 1,200 men volunteered in the 505th PIR alone. Source: “Four Stars of Valor: The Combat history of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2006 p. 121. As mentioned by Clair Blair and Jeff Moran, about fifty volunteered from the 504th. Significant numbers also volunteered from the 507th and 508th.

From this sizable pool of volunteers, there was a large number of men that weren’t chosen as pathfinders. Some of them would have been deemed unfit for the duty. Still, that would have left a number of men that were not chosen as pathfinders, but instead could have been chosen for training in the other special missions. More than likely, these men chosen for other missions would have possessed specialized skills, and it would have been an advantage to have had combat experience.

Bill had both. Besides his established combat experience, he had skills in finding the location of used parachutes and other air dropped equipment and recovering it in a way that incurred a minimum of damage. Skills that had been proven and honed under battle conditions. More broadly his basic skill set involved finding things in general and doing something with those things.

Moreover, Bill’s testament that he volunteered to jump with the 504 in Salerno was never satisfactorily explained. I had deduced that he jumped with the 2nd Battalion. However, now I wonder if he volunteered for the Pathfinders of the Salerno mission and somehow wound up jumping into Salerno in some capacity supporting them which potentially involved his post-jump rigger’s parachute and equipment recovery skills.

In any case, there is a connection between Gavin’s call for volunteers “…for other special missions” and Chester Polasky’s account of his brother Edward Polasky of the 508th jumping into Normandy on June 3 “…in one of the special operations prior to the Normandy invasion”. This gives credence to the possibility that the call for volunteers when recruiting pathfinders extended to picking men for other special missions, such as those told by Bill Clark and Edward Polasky’s brother, Chester.

Reasons for the need of Covert Missions before the D-Day invasion

Delicate Politics

From the very beginning of the alliance between France, Britain and America, political tensions had repeatedly arisen and they often emanated from the French General, Charles de Gaulle. Following the German annex of northern France in 1940, de Gaulle fled to Britain proclaiming that France was not conquered and would battle Germany with the help of Britain and America. After the installment of the German puppet Vichy government in France, de Gaulle was to eventually become the undisputed leader of the French Resistance, and the exiled de facto leader of France itself as recognized by the French people. Source: “The Moon is Down: The Jedburghs and Support to the French Resistance”, Jones, B., Master’s Thesis U. of Nebraska at Lincoln 1999 p. 6

Churchill, Roosevelt, and Eisenhower all experienced frustration and exasperation in dealing with de Gaulle. Following a private meeting with Stalin, de Gaulle successfully unified the Communist arm of the Resistance with those French partisans loyal to him. After this meeting, an intense distrust developed on the part of Roosevelt who thought de Gaulle would set up a dictatorship in France once the war was over. Source: “The Moon is Down: The Jedburghs and Support to the French Resistance”, Jones, B., Master’s Thesis U. of Nebraska at Lincoln 1999 p. 15

As D-Day approached, there was a failure on the part of Eisenhower, Roosevelt, Churchill, and de Gaulle to agree on matters of control over civil affairs after the invasion. If the invasion was a success, Roosevelt’s position was that America and Britain should govern France together until free French elections could be organized. Of course de Gaulle, with his post-war political ambitions, would have no part in this and stubbornly rejected the whole idea. Moreover, de Gaulle strongly objected to the proposed replacement of the pre-war French currency in favor of the use of the US occupation Franc which he considered to be “counterfeit money”. Without an agreement on these issues, Roosevelt would not recognize de Gaulle as the French leader. Eisenhower realizing the value of the French Resistance in support of the invasion desired greatly to work with de Gaulle. But de Gaulle would not work with the Allies unless the issue was settled in his favor. Source: “The Moon is Down: The Jedburghs and Support to the French Resistance”, Jones, B., Master’s Thesis U. of Nebraska at Lincoln 1999 pp. 19 - 20

Regardless of de Gaulle’s wishes, the US occupation Francs were printed and distributed to the troops before the invasion.

Eisenhower was deeply embarrassed by the failure to reach a resolution:

“Exasperated, Eisenhower wrote in his private journal on March 22nd, saying the President ‘has thrown back in my lap’ the resistance issue telling him [Eisenhower] to work with anyone ‘capable of assisting us.’ He desired to work with de Gaulle, but not singularly, and de Gaulle would not work with SHAEF [*] unless the Allies recognized his as the sole political authority. Only three days prior to D-Day, Eisenhower wrote ‘We have direct means of communications with the resistance groups of France but all our information leads us to believe that the only authority these resistance groups desire to recognize is that of de Gaulle and his committee. However, since de Gaulle is apparently willing to cooperate only on the basis of our dealing with him exclusively, the whole thing falls into a rather sorry mess.’ Interestingly, with all the other details of OVERLORD pressing down on Eisenhower, the politics of the French resistance was the first thing on his mind.” Source: “The Moon is Down: The Jedburghs and Support to the French Resistance”, Jones, B., Master’s Thesis U. of Nebraska at Lincoln 1999 pp. 19 - 20

* SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force)

It was only on June 4 that the relationship between the two men began to bear fruit when de Gaulle agreed to broadcast a radio message to the French Resistance along the same lines as Eisenhower’s famous message, more of which will be presented below. Source: “The Moon is Down: The Jedburghs and Support to the French Resistance”, Jones, B., Master’s Thesis U. of Nebraska at Lincoln 1999 p. 20

This warming of the relationship was too late for any overt special forces operations that were politically sanctioned by de Gaulle and coordinated with the French Resistance in support of the D-Day landings.

However, what about the possibility of covert special forces operations prior to the June 4 date?

Operation Jedburgh

Operation Jedburgh was the code name for a top secret operation established in 1942 by the SOE and the OSS with the objective of working with the French Resistance to undermine the Nazi occupation in France. Jedburgh missions were made up of three men – one of whom needed to be French. The teams comprised of two officers and the third man was a radio operator. Sometimes they were accompanied by SAS teams for mission security. They parachuted from the bomb bay of a Stirling or B-24 bomber into numerous locations in France. Their missions included cutting communication cables, and demolition of railway tracks, locomotives and bridges.

American Jedburgh operatives were recruited from airborne and ranger unit forces. Recruitment began in January of 1944 and by February it was complete. From among 62 American radio operators, 42 were selected by psychologists for acceptance into the training program. The Jedburgh’s (Jeds) trained north of London at Milton Hall a private estate that was requisitioned for military use. By May 1944, the program was finished and the Jeds were ready for mission assignments. Unfortunately for the Jeds, their missions were not launched until after D-Day to the dismay of Jedburgh team members.

One of the primary reasons for the delay of Operation Jedburgh was General de Gaulle, who would not allow their insertion into Normandy prior to D-Day unless his political demands to be recognized by Roosevelt and Churchill as the leader of France were met. Source: “The Moon is Down: The Jedburghs and Support to the French Resistance”, Jones, B., Master’s Thesis U. of Nebraska at Lincoln 1999 p. 1

SHAEF had made orders that teams of Operation Jedburgh were not to be sent into France 10 days before D-Day. Eisenhower explained in orders that it would be too great a risk to have personnel in France with OVERLORD plans. Later, closer to D-Day, (SHAEF) ordered Special Forces Headquarters (SFHQ) that no Jedburgh teams were to deploy into France before the night of D-Day –1. The SHAEF Chief of Staff, General Bedell Smith officially stated that he was fearful that putting Jedburgh teams into occupied France risked the exposure of OVERLORD. Source: “The Moon is Down: The Jedburghs and Support to the French Resistance”, Jones, B., Master’s Thesis U. of Nebraska at Lincoln 1999 p. 18 – 19

Operational Groups Composed of Americans

However, as the quotation below shows SHAEF did want (in addition to the Jedburgh teams) Operational Groups composed of American teams to be ready for insertion to destroy targets or for other objectives.

“A March 23, 1944 SHAEF Operations Directive ordered SOE/SO [SOE – the British Special Operations Executive and SO - the Special Operations Command of the US Office of Strategic Services or OSS] London to have seventy [Jedburgh] teams trained for D-Day. Eisenhower gave SOE/SO total control of resistance groups, who were as yet not clearly united behind any one person, and directed the resistance concentrate efforts against German air forces, lower the morale of German forces by sabotage, inflict damage on the German war effort in general, and prepare for the return of Allied Forces to the continent. Moreover, the document directed the equipping resistance groups by air drop. Jedburghs and Operational Groups (American teams of men deployed for the specific purpose of destroying a certain target or other such objective) were to be held ready by April 1, 1944. SHAEF clearly stated no invasion plan details should be conveyed to any resistance group, especially the date.” Source: “The Moon is Down: The Jedburghs and Support to the French Resistance”, Jones, B., Master’s Thesis U. of Nebraska at Lincoln 1999 p. 17 – 18

Note: The British SOE and the US OSS including the SO were combined into the Special Forces Headquarters (SFHQ) effective May 1, 1944. Despite the formal title of SFHQ, the SOE and SO were cooperating much earlier than May 1, 1944 as was indicated in the above Directive.

This Directive reflects the orders from Roosevelt, to work with any Resistance groups capable of assisting, which Eisenhower’s wrote of in his March 22 diary entry. However, three days before D-Day Eisenhower’s diary indicates that he did not fully trust the political allegiances of any Resistance groups.

It has been documented that some French Resistance groups under the control SFHQ’s “F Section” were still operating in France in the weeks before the invasion. (The “Independent French” or “F Section” had been set up by the SOE much earlier in 1940 and was composed of British controlled French Resistance groups. Most of these groups had had their leaders and some members captured, or had been exposed and were completely dismantled by German counter-intelligence. However, some of them had survived into 1944). To paraphrase Colin Beaven’s 2006 book “Operation Jedburgh” on this matter:

With the reduced manpower of the existing Allied agents from the old “F section” already operating in occupied France, in the early months of 1944 SFHQ dropped 187 additional agents into France, Belgium, and Holland. They were to organize their missions in support of the invasion before D-Day. SHAEF ordered SFHQ to use Resistance forces to impede German units sent to Normandy to reinforce the area in the last few days before D-Day. One of the plans (the “purple” AKA “violet” plan) focused on the use resistance groups to sabotage German communications. It worked around the knowledge of how German units were mobilized in WWII. When a German unit was activated an alert to mobilize was received via telephone. The SFHQ planners reasoned that among other attacks, enemy installations could be assaulted to disable transmission centers and key communication cables could be severed. Maps of these enemy assets were drawn with pins inserted at the locations of nearby Resistance groups and Allied agents who could carry out the corresponding sabotage missions. In the months before D-Day, SFHQ communicated mission objectives to these groups. In the few days before D-Day, the deployed SFHQ F Section teams were ready to carry out their orders. Source: “Operation Jedburgh” Beaven, C., 2006 pp. 100 -101

From this information, it is reasonable to surmise that – despite Eisenhower’s misgivings entered in his diary three days before D-Day – some of these Resistance groups would give their support to the other special missions, for instance, in cases where groups were of reduced ranks, without leadership, and/or without the direction of an Allied agent. A particular example would have been the communications sabotage mission Bill said he was given.

Unlike the case of the Jedburgh’s, there is no reference to restrictions on the date of insertion into Normandy for the American Operational Group teams in any of the material presented in the source “The Moon is Down: The Jedburghs and Support to the French Resistance” by Benjamin Jones. Indeed, according a document published by the OSS in 1945 detailing its organization and functions:

“The OG (Operational Group) Command organizes and operates guerrilla forces in deep penetration operations. In China, and in other places, it has trained and officered guerrilla bands recruited abroad. In France just prior to and immediately after D-day the OG Command dropped groups for liaison and support to the Maquis.” Source: “Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Organization and Functions” Schools & Training Branch, June 1945 p. 6. Retrieved from: http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USG/JCS/OSS/OSS-Functions/

One balance, this evidence supports the notion that American Operational Group teams were inserted into France just prior to D-Day to supplant the networks from SFHQ’s “F section”. The confirmed case of George Hjorth and his established presence in Normandy three days before the invasion with a mission to “film what he saw” at Omaha Beach also provides strong support to this notion.

Hjorth clearly had the support of the local French Resistance in Normandy. SFHQ must have had the support of the local French Resistance in Normandy or they would not have agreed to help; would not have known that Hjorth was coming; nor where to pick him up; nor lead him in the darkness to the best place to take the pictures.

Hjorth’s mission could hardly be a called a primary objective. Taking pictures would be of secondary importance, to securing the invasion area by disrupting and otherwise cutting lines of communications and electrical power in the area. Yet Hjorth’s mission did take place.

In the case of the OSS operative, Al Tanz. He must have had the support of French Resistance in Normandy and their local knowledge to carry out his mission of cutting electrical wires behind the beaches. He would have needed a hiding place in daylight hours. Moreover, his Communist roots might have been an advantage if the local French Resistance members were Communists, as many French Resistance groups were. As a veteran of the ALB, fighting against the Nazi backed Spanish Nationalists, his credentials may well have been beyond the reproach of any French Resistance group and a key factor in his being chosen for the mission.

In the Hjorth case, details of when the invasion was to take place were not known. This was a paramount stipulation which Eisenhower emphasized in his March 23 directive referenced above. Moreover, Hjorth said he did not even know an invasion was going to happen:

“Only when the invasion began did he [Hjorth] learn that his mission was to film the D-day landing of the U.S Army's 1st Infantry Division and the 29th Infantry Division at Omaha Beach--from the German side.” Source 3: Putting D-Day in Focus: Photographer Sheds Light on Mission Behind Nazi Lines” by Reza H. G., Los Angles Times, October 22, 1988 retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/1998/oct/22/local/me-35058

In the cases of Bill Clark, Edward Polasky, and Al Tanz it is reasonable that these same precautions were taken.

The arguments and the facts of the Hjorth and Joseph Beyrle missions, demonstrate that Eisenhower must have found a way to “work with anyone ‘capable of assisting us.’” (as President Roosevelt had asked him to do). That is, well before June 3, 1944, his efforts to do so must have resulted in the cooperation of the French Resistance groups in Normandy, probably with those loyal to SFHQ’s “F section” and that SHAEF used the resources of the SFHQ to drop men into Normandy fully aware of the risks in doing so. Joseph Beyrle said his mission to deliver gold to Resistance groups occurred in April and in May. This would imply that such cooperation had been at least partially achieved by as early as April, 1944.

Common Arguments Against These Missions

Language Barrier

One argument against the use of American paratroops, such as Bill Clark ,is that he could not speak French and that would preclude him and others from being part of these missions. The accounts of the French Resistance in Normandy, however, lend credence to the reality that small numbers American paratroopers (who did not speak French) were inserted into Normandy at least three days before the invasion . One of these accounts explicitly refers to the use of interpreters. In the case of the first paragraph it states that:

“Mrs. LANGLOIS and teacher LECLER served as the interpreters.”

The Men Knew Details About the Invasion Plans

Another argument commonly presented against these missions in principle is that these men knew what the broader scope of their mission was. In the case of George Hjorth, he did not know what his mission was, except that he was told to take pictures of what he saw on a beach. He did not even know where he was in France. He certainly did not know when the invasion would take place, nor that there was even going to be an invasion on that beach. Hjorth’s case shows that men parachuted into Normandy before the invasion were only given information specific to their mission. Based on Hjorth’s case, details of where they were and the reasons for the mission were not provided and were not necessary for them to accomplish the missions. If they were caught, it might have been possible that the larger picture could have been constructed by the Germans. Despite this exposure, the reality of Hjorth’s case demonstrates that SHAEF was willing to take the risk.

Implications of a Late Decision on the Precise Date of the Invasion Precluded Missions on June 3, 1944

Often it is argued that no June 3, nor June 4, 1944 parachute missions into Normandy were possible because even by June 3, the final decision had not been made to launch D-Day as planned on June 5.

Due to the bad weather, Eisenhower was forced to delay the invasion which was scheduled for the morning of June 5, (with the airborne component of the plan to be executed on the night of June 4/5):

“…D day had originally been scheduled by the Combined Chiefs of Staff for the ‘favorable period of the May moon.’ Later, on Eisenhower’s recommendation, they postponed D day to a ‘favorable period’ in June. The specific date would be left to the discretion of the Supreme Commander. But in choosing the actual D day, Eisenhower was at the mercy of the tides. For the lunar cycle left us with only six days each month when tidal conditions fulfilled our requirements on the beaches. The first three fell on June 5, 6, and 7.” Source: “Bradley: A Soldier’s Story” Bradley, O., 1951 p. 259

“…June 6 would best fit our requirements, for it would have sufficient daylight before the incoming tide would reach the obstacles on Omaha Beach. June 5 would be acceptable with 30 minutes less daylight, June 7 with 30 minutes more…Ike’s first choice for D day had been June 5. For then if weather closed in, he could still choose June 6 or 7. Consequently, on May 17 he red-lined June 5 as D Day.” Source: “Bradley: A Soldier’s Story” Bradley, O., 1951 p. 261

At 9:45 PM on Sunday evening, June 4, Eisenhower made his famous decision to postpone Operation OVERLORD from the scheduled date of June 5 until June 6, hoping the slim chance that the forecast break in weather would hold to make the beach landings on June 6. Source: “Bradley: A Soldier’s Story” Bradley, O., 1951 p. 263

Furthermore, if the weather did not improve, the invasion would have been postponed until either the second favorable lunar cycle which occurred in late June or if the weather precluded that possibility, the invasion would have been put off until a favorable moon phase in July, 1944. Source: “Bradley: A Soldier’s Story” Bradley, O., 1951 p. 259

The argument that parachute missions into Normandy on the nights of June 3 and 4 could not have happened is based on three false assumptions. The first is that the men performing the mission would have given away the timing of the invasion. In fact, it would have been better that they did not know the date as was the case with George Hjorth. Indeed, Hjorth did not even know an invasion was on until he saw the armada off the coast on June 6 when he executed his mission.

The second false assumption is that some of these men such as Bill Clark and Edward Polasky wore the uniform of the 82nd Airborne and if captured, that would have been proof that the invasion was imminent and the location was Normandy. Wearing a uniform does not necessarily mean that an invasion is imminent, nor the location. It is possible that these men did not wear uniforms, (as was reported by the French Resistance account in the Paragraph 2 section near the beginning of this blog post) but instead were dressed in civilian clothing, thus forfeiting their rights (if caught) under the Geneva Convention and executed as spies. It is also possible that they did wear their uniforms and if caught would have been tried as Allied prisoners of war. There were scores of commando raids made by the Allies behind enemy lines in WWII in which the men wore their uniforms. A paratrooper in his uniform didn’t necessarily mean an invasion. Furthermore, they could have easily worn the uniform of a downed Allied airman and used that as a cover story if caught. In fact there is a precedent to this tactic which was posted in an earlier blog post. When General Maxwell Taylor went on his secret mission to Rome, he and Colonel William Gardiner were disguised as captured airmen shot down and taken prisoner. They were dressed in these uniforms so that if caught would have a better chance of not being shot as spies.

The third false assumption is related to the point made above that these missions could not have taken place on June 3 because the final date for the invasion was not set. The fact is the US Airborne units thought the seaborne invasion was on for June 5 as evidenced by the paratroopers making final preparations to take off on the night of June 4/5. On the airfields in the English midlands, the 505 PIR was making preparations for Operation NEPTUNE, the code name for the jump into occupied Normandy. On June 4, the men were fed a good meal prior to takeoff. News of Eisenhower's decision to postpone the invasion reached them before their planes were due to take off. They were informed that the operation had been postponed until the night of June 5/6. Source: “Four Stars of Valor: The Combat history of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II” Nordyke, P., 2006 p. 126

Furthermore, like the pathfinders, the men of these special missions were most likely told they were on a suicide mission which involved being dropped behind enemy lines. There, they would be met by the French Resistance and wait in hiding until the signal was given to execute their missions. In other words, like the French Resistance teams, they did not need to know that an invasion was on, nor the timing of it. They would have been told that once their missions were complete, they would be extracted, just as Joseph Beyrle of the 101st Airborne was extracted after delivering his gold coins to the Resistance in April and May. All they needed to know was the particulars of their mission – to cut power and communications cables, or to take photographs, etc, when the signal was given.

These men would have guessed or known that help may never come and that they would probably die. In the case of the 82nd Airborne paratroopers, they were men who did not care where they jumped and were willing, even eager and excited to have the chance to take such daring risks. This much can be inferred from accounts of pathfinders who “…accepted that their chances of living through the invasion were next to nothing… ‘some of them, like the pathfinders, didn’t have a prayer’” Moreover, “…pathfinders were anxious to get into combat as soon as possible, regardless of the consequences…” Source: “If Chaos Reigns: The Near-Disaster and Ultimate Triumph of the Allied Airborne Forces on D-Day, June 6, 1944” Whitlock, F., 2011, p. 88.

Late Changes in Mission Objectives

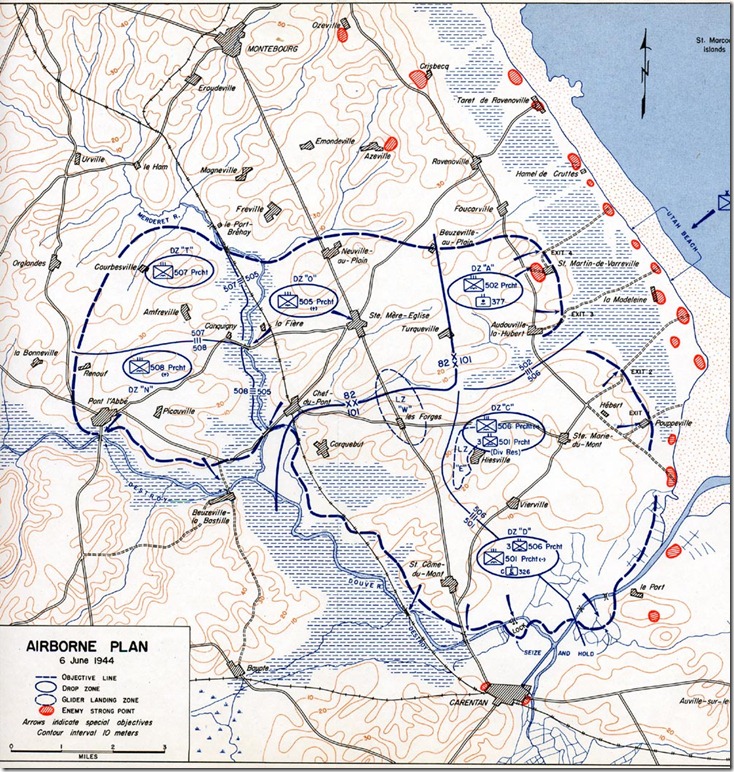

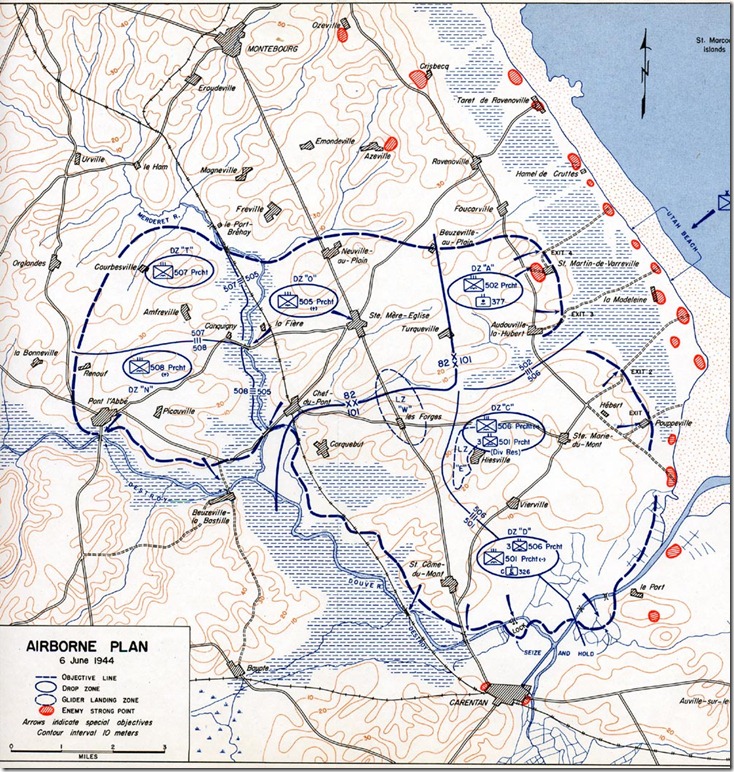

A final argument is that the objectives of the 82nd Airborne were changed on May 26 from capturing and securing the area around St.-Sauveur-le-Vicomte to “…seize, clear, and secure the general area of Neuville-au-Plain, Ste.-Mere-Eglise, Chef-du-Pont, Etienville, Amfreville. It was to destroy crossings over the Douve…”. Source: “On To Berlin: Battles of an Airborne Commander 1943 – 1946” Gavin, J., 1978 p. 98

If any mission requiring coordination with the French Resistance was to happen, then potentially changes would have needed to be made with the French Resistance to ensure a safe rendezvous and an adequate place to hide closer to the new 82nd Airborne objectives. There is no reason to believe that this goal could not have been achievable in the seven days between the change of objectives and the mission itself. In addition, the specific objectives of Bill’s mission might change to some degree with differences in the location of the power lines and communications cables. Again, there is no reason to believe that this situation would have caused a scrapping of the mission, since the missions and objectives of many other 82nd units objectives needed to change too and were changed accordingly. The men simply rehearsed their new missions and were ready in time for the invasion.

Why not Just Leave such Missions to the French Resistance?

The account of the French Resistance – “La Manche mouvements de résistance” (http://beaucoudray.free.fr/1940.htm) tells a grim tale of the Resistance in Normandy leading up to the invasion. By June 1, 1944, the document recounts that many Resistance fighters were captured by the Germans or killed in bombing raids. It was estimated that there were only 400 fighters in the southern sector and 700 in the Cotentin region. The document also records that the Resistance had a very meager, even “ridiculously insufficient” supply of weapons, with reports of only one-quarter and even one-tenth of what they were promised or needed to carry out their tasks. The document also states that members were excited and willing to fight, but were concerned due to the variability of the numbers of fighters across the different groups, poor equipment, and lack of sufficient armband insignia to identify persons as Resistance fighters. Source: “La Manche mouvements de résistance” Sections LA MOBILISATION DES F.F.I.; DISPOSITION DES GROUPES E,FI. AU DÉBUT DE JUIN; A RÉPARTITION DE L'ARMEMENT Retrieved from http://beaucoudray.free.fr/1940.htm

With the reduction in the numbers of Resistance operatives, it would appear to make sense to send in small teams of men to increase the chances that sabotage objectives of power and communications were achieved. This approach would be especially true in cases where the SFHQ “F section” Resistance groups were too weakened and may not have had enough members with the skills to disrupt communications, cut power lines, and demolish roads and railways.

Timeline of Bill’s Mission

Soon after Bill arrived in England, he would have heard about the call for volunteers for secret missions. He had already volunteered to jump into Salerno, so he may have already been on a short list of some sort. Subsequently, he was picked and attended British parachute training school, just as Joseph Beyrle of the 506th PIR, 101st Airborne had done. He would have then trained in cutting telephone cables, perhaps underground or above ground, possibly both. This training probably extended to include communications disruption techniques such as reversing road signs, removing them, or replacing them with false signs. More training would have involved evasion and silent close quarters killing techniques. Night jump training would have been part of his regimen. To hone his skills he would have made many jumps, just as is reported in the instance of the 82nd pathfinders. As an aside, Bill had an impressive 52 combat condition jumps at the end of the war.

It is likely that Bill and Al Tanz were on closely related teams. At the very least, their missions were in the same area. In Al Tanz’ case, he was to cut electrical wires behind the beaches. Afterwards, he fought with the 82nd Airborne troopers to liberate Sainte-Mere-Eglise. According to Bill’s own testimony as recorded in the previous posts on Normandy, he fought in Sainte-Mere-Eglise on D-Day.

Indeed, capture of Sainte-Mere-Eglise was a lynchpin that would give the Allied Invasion the highest chance for success on its Eastern flank. The whole of Operation Neptune would be placed in grave jeopardy if the town fell into German hands. It was positioned at a crossroads on a long strip of land higher than the surrounding flooded countryside. A major road leading from Cherbourg behind Utah beach ran through Sainte-Mere-Eglise to Caen via Carentan. (See Map 1). Other roads in the east led to Utah beach from Chef-du-Pont, and from the causeway at La Fiere. Control of these area roads was crucial for ensuring the defense of the landing zones on the Normandy beaches and especially for the U.S. 4th Infantry Division whose first objective was to assault Utah beach and establish a beachhead. Because everything depended on this mission, it was assigned to the 505 since it was the only American airborne regiment in the invasion forces with prior combat experience via Sicily and Italy.

Map 2: Operation Neptune Plan

Source: “War Chronicle Normandy: US Airborne Picture File” Retrieved from http://warchronicle.com/dday/utah/normandy_us_airborne_pics.htm

Clearly then, Sainte-Mère-Église was the choke point at which the Germans must be stopped. Every possible measure needed to be taken to ensure they could not reach the beaches. It is not surprising to hear of reports from veterans that this extended to include special missions prior to D-Day, to cut communication cables and power cables in the area and disrupt communications. Switching road signs in a pre-determined pattern designed to optimally turn the direction of German traffic away from the beaches would have helped significantly. This operation is something the French Resistance would have had difficulty in planning, since it would have taken a traffic planning expert with aerial photographs to devise a plan to change road signs in such a way as to maximize confusion and eventual distance from the beaches of reinforcing German units.

Bill’s mission must have been to cut communication cables and disrupt communications in the area around Sainte-Mere-Eglise, beginning when the BBC coded messages were broadcast on the evening of June 5.

“One the first day of June, the BBC had broadcast a secret message which served to alert circuit organizers and resistance leaders that the invasion was only days away. Resistance groups had then listened every evening for their second pre-arranged message, which would be their execute order. Plans called for D-Day targets to be struck forty-eight hours after the receipt of this second message.

At nine-fifteen on the evening of June 5, following the BBC’s French news broadcast, the seemingly meaningless personal messages, the execute orders – 306 in all – had gone out over the air.” Source: “The Jedburgh’s”, Irwin, W., 2005 p. 79

The planners of his mission must have believed that there was a good chance that the airborne component of the invasion was to occur on the night of June 4/5. That is why the June 1 BBC coded message informed that Resistance that the invasion was only days away.

It is almost certain that he parachuted in the pre-dawn hours of June 3 to take advantage of the cover of darkness. That would have given him the pre-dawn hours to link up with Resistance members before having to hide with them for the daylight hours of June 4. He would not have known that an invasion was going to occur, nor when. It is logical to assume that he would have been in the dark, just as George Hjorth had been. That is, he would have only known that he was to cut communication cables following a certain procedure and using tools he may have brought with him to do it. He would have been hidden by the Resistance group in a safe location. They would have listened to the radio on the nights of June 3 and 4. On June 5, they would have been excited to hear news that the invasion was beginning that night. They would have heard the code words for the mission to cut communications cables and disrupt communications, and informed Bill whom would then have swung into action.

Conclusion

George Hjorth’s story has since been verified by numerous sources, but you will not find a record of him in the OSS personnel file found online at http://www.archives.gov/iwg/declassified-records/rg-226-oss/personnel-database.pdf. John Ford is found in those files as is Al Tanz. George Hjorth is an example of what typifies research in the discipline of History. The people and events they participated in are not always well documented. Fortunately, George Hjorth’s story can be verified by numerous eye witnesses which have come forth to support his involvement in the pre D-Day mission and his version of those events.

Perhaps documentary evidence will never be found for any of these other special missions. In the face of mounting evidence, in the form of the recorded French accounts, and the corroborative American accounts discovered so far, it is clear American paratroopers parachuted into Normandy three days or more before D-Day possibly as one off members of OSS teams on temporary assignment.

Given the facts uncovered so far, it would appear that a serious investigation is warranted.

My challenge to the historical research community is simple. Perform the research and find evidence that proves the issue one way or another; that 82nd Airborne paratroopers such as William Clark and Edward Polasky did or did not parachute into Normandy three days before D-Day. Such evidence might be difficult to find. These missions were possibly ‘off the books’ due to the documented problems faced by the Jedburghs involving de Gaulle’s reluctance to send Jedburgh teams into France before D-Day. This situation in turn likely led to the necessity for the OSS, the 82nd Airborne, the 101st Airborne, and others to work together to train and drop teams into France to ensure communications, power, and transportation systems were disrupted during the landings.

Postscript

While composing this post, I was surreptitiously contacted by a descendent of a 504th PIR veteran who has good reason to believe his uncle was a pathfinder in Normandy. However, the trooper’s name is not listed in the published rosters of the 82nd Airborne pathfinders. Based on the evidence presented in this post, I believe this trooper could have been a member of a team assigned to one of the other special missions, just as Edward Polasky was reported to have been.

How many other families of troopers have similar stories?

Surely my research has only scratched the surface and there are more credible accounts waiting to come to light.

Therefore, I encourage those of you who do have such stories in your family history to come forth with them. The troopers who took the risks to accomplish these missions deserve recognition. If enough credible accounts start to be told, the chances are good that a professional researcher will take them seriously and a lost chapter of the history of the Normandy invasion will be salvaged before it becomes too late.

© Copyright Jeffrey Clark 2013 All Rights Reserved.